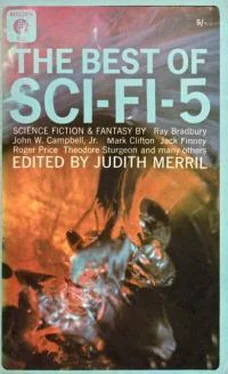

The Best of Sci-Fi-5

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «The Best of Sci-Fi-5» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1966, Издательство: Mayflower-Dell, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Best of Sci-Fi-5

- Автор:

- Издательство:Mayflower-Dell

- Жанр:

- Год:1966

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Best of Sci-Fi-5: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Best of Sci-Fi-5»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Best of Sci-Fi-5 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Best of Sci-Fi-5», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Matter of fact,” I admitted, “I have. The Company has sharp pencils. If I didn’t keep up my records, they’d take the fillings out of my teeth before I knew what was happening. I didn’t have humans, so I trained goonies to do the job. Under detailed instruction, of course,” I added.

“I need such a clerk, myself,” he said. “There’s a new office manager, fellow by the name of Carl Hest. A—well, maybe you know the kind. He’s taken a particular dislike to me for some reason—well, all right, I know the reason. I caught him abusing his rickshaw goonie, and told him off before I knew who he was. Now he’s getting back at me through my reports. I spend more time making corrected reports, trying to please him, than I do in mining libolines. It’s rough. I’ve got to do something, or he’ll accumulate enough evidence to get me shipped back to Earth. My reports didn’t matter before, so long as I brought in my quota of libolines—the clerks in Libo City fixed up my reports for me. But now I’ve got to do both, with every T crossed and I dotted. It’s driving me nuts.”

“I had a super like that when I was a Company man,” I said, with sympathy. “It’s part of the nature of the breed.”

“You train goonies and sell them for all other kinds of work,” he said, at last. “I couldn’t afford to buy an animal trained that far, but could you rent me one? At least while I get over this hump?”

I was reluctant, but then, why not? As Paul said, I trained goonies for all other kinds of work, why not make a profit on my clerks? What was the difference? And, it wouldn’t be too hard to replace a clerk. They may have no intelligence, as the psychologists defined it, but they learned fast, needed to be shown only once.

“About those kangaroos,” I said curiously. “How did that author justify calling them stupid?”

Paul looked at me with a little frown.

“Oh,” he said, “various ways. For example, a rancher puts up a fence, and a chased kangaroo will beat himself to death trying to jump over it or go through it. Doesn’t seem to get the idea of going around it. Things like that.”

“Does seem pretty stupid,” I commented.

“An artificial, man-made barrier,” he said. “Not a part of its natural environment, so it can’t cope with it.”

“Isn’t that the essence of intelligence?” I asked. “To analyze new situations, and master them?”

“Looking at it from man’s definition of intelligence, I guess,” he admitted.

“What other definition do we have?” I asked….

I went back to the rental of the goonie, then, and we came to a mutually satisfactory figure. I was still a little reluctant, but I couldn’t have explained why. There was something about the speaking, reading, writing, clerical work—I was reluctant to let it get out of my own hands, but reason kept asking me why. Pulling a rickshaw, or cooking, or serving the table, or building a house, or writing figures into a ledger and adding them up—what difference?

In the days that followed, I couldn’t seem to get Paul’s conversation out of my mind. It wasn’t only that I’d rented him a clerk against my feelings of reluctance. It was something he’d said, something about the kangaroos. I went back over the conversation, reconstructed it sentence by sentence, until I pinned it down.

“Looking at it from man’s definition of intelligence,” he had said.

“What other definition do we have?” I had asked.

What about the goonie’s definition? That was a silly question. As far as I knew, goonies never defined anything. They seemed to live only for the moment. Perhaps the unfailing supply of fruit from their pal tree, the lack of any natural enemy, had never taught them a sense of want, or fear. And therefore, of conscience? There was no violence in their nature, no resistance to anything. How, then, could man ever hope to understand the goonie? All right, perhaps a resemblance in physical shape, but a mental life so totally alien …

Part of the answer came to me then.

Animal psychology tests, I reasoned, to some degree must be based on how man, himself, would react in a given situation. The animal’s intelligence is measured largely in terms of how close it comes to the behavior of man. A man would discover, after a few tries, that he must go around the fence; but the kangaroo couldn’t figure that out—it was too far removed from anything in a past experience which included no fences, no barriers.

Alien beings are not man, and do not, cannot, react in the same way as man. Man’s tests, therefore, based solely on his own standards, will never prove any other intelligence in the universe equal to man’s own!

The tests were as rigged as a crooked slot machine.

But the goonie did learn to go around the fence. On his own? No, I couldn’t say that. He had the capacity for doing what was shown him, and repeating it when told. But he never did anything on his own, never initiated anything, never created anything. He followed complicated instructions by rote, but only by rote. Never as if he understood the meanings, the abstract meanings. He made sense when he did speak, did not just jabber like a parrot, but he spoke only in direct monosyllables—the words, themselves, a part of the mechanical pattern. I gave it up. Perhaps the psychologists were right, after all.

A couple of weeks went by before the next part of the pattern fell into place. Paul brought back the goonie clerk.

“What happened?” I asked, when we were settled in the living room with drinks and pipes. “Couldn’t he do the work?”

“Nothing wrong with the goonie,” he said, a little sullenly. “I don’t deserve a smart goonie. I don’t deserve to associate with grown men. I’m still a kid with no sense.”

“Well, now,” I said with a grin. “Far be it from me to disagree with a man’s own opinion of himself. What happened?”

“I told you about this Carl Hest? The office manager?”

I nodded.

“This morning my monthly reports were due. I took them into Libo City with my libolines. I wasn’t content just to leave them with the receiving clerk, as usual. Oh, no! I took them right on in to Mr. High-and-mighty Hest, himself. I slapped them down on his desk and I said, ‘All right, bud, see what you can find wrong with them this time.’”

Paul began scraping the dottle out of his pipe and looked at me out of the corner of his eyes.

I grinned more broadly.

“I can understand,” I said. “I was a Company man once, myself.”

“This guy Hest,” Paul continued, “raised his eyebrows, picked up the reports as if they’d dirty his hands, flicked through them to find my dozens of mistakes at a glance. Then he went back over them—slowly. Finally, after about ten minutes, he laid them down on his desk. ‘Well, Mr. Tyler,’ he said in that nasty voice of his. ‘What happened to you? Come down with an attack of intelligence?’

“I should have quit when my cup was full,” Paul said, after I’d had my laugh. “But oh, no. I had to keep pouring and mess up the works—I wasn’t thinking about anything but wiping that sneer off his face. ‘Those reports you think are so intelligent,’ I said, ‘were done by a goonie.’ Then I said, real loud because the whole office was dead silent, ‘How does it feel to know that a goonie can do this work as well as your own suck-up goons—as well as you could, probably, and maybe better?’

“I walked out while his mouth was still hanging open. You know how the tenderfeet are. They pick up the attitude that the goonie is an inferior animal, and they ride it for all it’s worth; they take easily to having something they can push around. You know, Jim, you can call a man a dirty name with a smile, and he’ll sort of take it; maybe not quite happy about it but he’ll take it because you said it right. But here on Libo you don’t compare a man with a goonie—not anytime, no how, no matter how you say it.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Best of Sci-Fi-5»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Best of Sci-Fi-5» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Best of Sci-Fi-5» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.