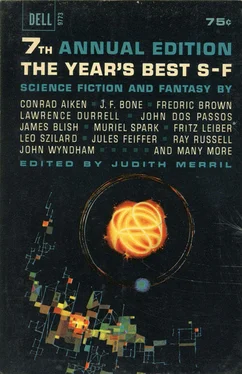

Judith Merril - The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 7

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Judith Merril - The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 7» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1963, Издательство: Dell, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 7

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dell

- Жанр:

- Год:1963

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 7: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 7»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 7 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 7», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Now, his space ship irretrievably wrecked, he was crawling through the dark on the frozen gray sands of Asteroid Zero — so named by him because it was uninhabited, had no precious metals, and was even unvegetated because sunless through being in the eternal shadow of giant Jupiter. Argo’s destination, as he crawled, was the cave of The Last Wizard. All other wizards had been wiped out in Argo’s Holy Campaign Against Sorcery, but it was rumored one wizard had escaped to Zero. Argo silently prayed the rumor was true and The Last Wizard still alive.

He was: revoltingly old, sick, naked, sunken in squalor, alive only through sorcery — but alive. “Oh, it’s you,” were the words with which he greeted Argo. “I can’t say I’m surprised. You need my help, eh?”

“Yes, yes!” croaked Argo. “Conjure for me a disguise they cannot penetrate I I entreat, I implore you!”

“What kind of disguise might that be?” cackled The Last Wizard.

“I know for a fact,” said Argo, “because wizards have confessed it under torture, that all human beings are weres — that the proper incantation can transform a man into a werewolf, a weredog, a werebird, whatever were-creature may be locked within his cellular structure. As such a creature, I can escape undetected!”

“That is indeed true,” said The Last Wizard. “But suppose you become a werebug, which could be crushed underfoot? Or a werefish, which would flip and flop in death throes on the floor of this cave?”

“Even such a death,” shuddered Argo, “would be better than a legal execution.”

“Very well,” shrugged The Last Wizard. He waved his hand in a theatrical gesture and spoke a thorny word.

That was in July of 2904. A hundred years later, in July of 3004, Argo was still alive on Zero. He could not, with accuracy, be described as happy, however. In fact, he now yearns for and dreams hopelessly of the pleasures of a death under the Black Elixir. Argo had become that rare creature, a werevampire. A vampire’s only diet is blood, and when the veins of The Last Wizard had been drained, that was the end of the supply. Hunger and thirst raged within Argo. They are raging still, a trillionfold more intense, for vampires are immortal. They can be killed by a wooden stake through the heart, but Zero is unvegetated and has no trees. They can be killed by a silver bullet, but Zero can boast no precious metals. They can be killed by the rays of the sun, but because of Jupiter’s shadow, Zero never sees the sun. For this latter reason, Argo is plagued by an additional annoyance: vampires sleep only during the day, and there is no day on Zero.

TO AN ASTRONAUT DYING YOUNG

by Maxine W. Kumin

Mrs. Kumin has published one book of poetry (Halfway, Holt, 1961), and several children’s books. She is an instructor in English at Tufts University, currently on leave to study on a Radcliffe grant.

Tell us: are you dead yet? The elephant ears of our radar still read you, wobbling over our heads like a baby star.

They say you will orbit us now once every ninety minutes for years. And nothing about you will rot in your climate.

Down here it is spring. Whole townships huddle outdoors in the evening,

round-eyed as the cattle once were, but this time watching and waving

as your little light winks overhead, as it tilts and veers to the west.

You sit in the contour chair that fitted your torso best

but by summer, who will still think to measure your perigee?

Only the faithful few who set up a rescue committee.

Such ingenuity! Think now; can God have invented it?

We know that when planes crack open and spill the unlucky ones out,

there are tag ends to go on. He stands by to pick up the pieces

we label, and grieving, hand back to His care at requiem masses.

Even the dead at sea have a special path to His bosom.

Combing the mighty waves, He grapples up souls from the bottom.

But there you go again, locked up in your perfect manhood,

coasting beyond the reach of the last seraph in the void.

Not one levitating saint can rise from the golden pavement

high enough over the ridgepole to yank you back into His tent.

This was a comfortable kingdom, the dome of it tastefully pearled

till you cut loose. Your kind of death is out of God’s world.

SUMMATION: S-F, 1961

by Judith Merril

For some years now, those of us working in what even we still quaintly call “the science-fiction field” have been increasingly aware of the floating-island nature of that “field.” And if it seemed at times that we were simply drifting out to sea, it is now becoming sharply evident that the direction of drift, all along, was into the “mainstream.” The specialized cult of science fiction (for which many of us still, and I expect will, feel a lingering nostalgia) is rapidly disappearing, as the essential quality is absorbed into the main body of literature.

More properly, I should say, reabsorbed. S-f had its beginnings in mainstream writing. The literary-sociological analysis of the compartmentalizing of this kind of fiction during the first half of the twentieth century will undoubtedly provide scholastic adventure for innumerable future thesis-writers. For those of us actively interested in the (flooded) field at the present time, it is enough to understand that the reabsorption has not been one-sided. For any prodigal to effect his return, it is necessary not only that the parent body be prepared to offer welcome, but that the wanderer has found cause to come home.

These causes have been varied and complex, ridiculous and sublime: they have included such things as the influence of “the syndicate” on magazine distribution, the International Geophysical Year, Kingsley Amis’ book of lectures and Willy Ley’s lectures on books. (The rest of the list I leave to those scholars of tomorrow.) But whatever the causes, the results are obvious.

At the beginning of 1956, when the First Annual of this series was being readied for the press, I counted thirteen science-fiction magazines in this country, and four more in England. (Most of them were quarterlies or bimonthlies; it averaged out to about ten altogether each month.) That first annual contained, proudly, three (out of eighteen) stories from sources outside the specialty magazines; the Honorable Mentions listed seven more. And the Summation pointed with a sort of ghetto pride to the fact that thirty or forty of Our Kind of Stories had crossed the line in ‘55, and found respectable lodging in literary and “slick” magazines.

This year, sixteen of the thirty fiction and verse selections are from general fiction magazines, or books. There are five s-f magazines published here, and two in England — five-and a half a month average, with the three bimonthlies.

In ‘56, I was able to include three “name” writers from outside the specialty field. This year, there are only thirteen stories by writers known in the field. Most striking is the number of writers from non-fiction fields who have made their first story efforts in s-f; most gratifying is the growing number of serious young writers who are devoting themselves equally to s-f and “quality” media.

This is the internal evidence. From outside come such items as the previously mentioned seminar of the Modern Language Association (or the word from my scout in Sausalito that s-f is the top seller in the beatniks’ favorite bookstore). There is The Twilight Zone on TV, which no one (except us Old School Ties) thinks of as s-f. There is The Saturday Evening Post, printing without special comment an average of one fantasy or s-f story per issue….

Which brings up a point. The welcome offered to s-f is warm, as only a homecoming can be. But by the same token, the critics, editors, reviewers, publishers, who are uncle and aunt, elder brother, sister, and cousins, who all stayed correctly at home while we went wandering in lurid pulp-paper lands, are not prepared to meet us on the grounds of our own choosing — and certainly not to recognize us by the identity we assumed “outside.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 7»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 7» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 7» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.