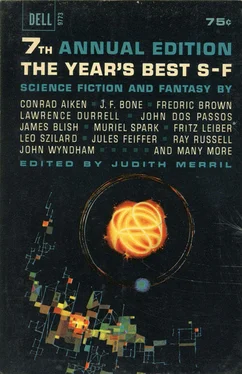

Judith Merril - The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 7

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Judith Merril - The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 7» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1963, Издательство: Dell, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 7

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dell

- Жанр:

- Год:1963

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 7: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 7»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 7 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 7», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

For two generations the surviving nations were far too occupied by the tasks of bringing equilibrium to a half-wrecked world to take any interest in scattered islands. It was not until the Brazilians began to see Australia as a possible challenger of their supremacy that they started a policy of unobtrusive and tactful mercantile expansion into the Pacific. Then, naturally, it occurred to the Australians, too, that it was time to begin to extend their economic influence over various island-groups.

The New Caledonians resisted infiltration. They had found independence congenial, and steadily rebuffed temptations by both parties. The year 2194, in which Space declared for independence, found them still resisting; but the pressure was now considerable. They had watched one group of islands after another succumb to trade preferences, and thereafter virtually slide back to colonial status, and they now found it difficult to doubt that before long the same would happen to themselves when, whatever the form of words, they would be annexed — most likely by the Australians in order to forestall the establishment of a Brazilian base there, within a thousand miles of the coast.

It was into this situation that Jayme Gonveia, speaking for Space, stepped in 2150 with a suggestion of his own. He offered the New Caledonians guaranteed independence of either big Power, a considerable quantity of cash, and a prosperous future if they would grant Space a lease of territory which would become its Earth headquarters and main terminus.

The proposition was not altogether to the New Caledonian taste, but it was better than the alternatives. They accepted, and the construction of the Space-yards was begun.

Since then the island has lived in a curious symbiosis. In the north are the rocket landing and dispatch stages, warehouses, and engineering shops, and a way of life furnished with all modem techniques, while the other four-fifths of the island all but ignores it, and contentedly lives much as it did two and a half centuries ago. Such a state of affairs cannot be preserved by accident in this world. It is the result of careful contrivance both by the New Caledonians who like it that way, and by Space which dislikes outsiders taking too close an interest in its affairs. So, for permission to land anywhere in the group one needs hard-won visas from both authorities. The result is no exploitation by tourists or salesmen, and a scarcity of strangers.

However, there I was, with an unexpected week of leisure to put in, and no reason why I should spend it in Space-Concession territory. One of the secretaries suggested Lahua as a restful spot, so thither I went.

Lahua has picture-book charm. It is a small fishing town, half-tropical, half-French. On its wide white beach there are still canoes, working canoes, as well as modem. At one end of the curve a mole gives shelter for a small anchorage, and there the palms that fringe the rest of the shore stop to make room for the town.

Many of Lahua’s houses are improved-traditional, still thatched with palm, but its heart is a cobbled rectangle surrounded by entirely untropical houses, known as the Grande Place. Here are shops, pavement cafés, stalls of fruit under bright striped awnings guarded by Gauguinesque women, a statue of Bougainville, an atrociously ugly church on the east side, a pissoir, and even a Maine. The whole thing might have been imported complete from early twentieth-century France, except for the inhabitants — but even they, some in bright sarongs, some in European clothes, must have looked much the same when France ruled there.

I found it difficult to believe that they are real people living real lives. For the first day I was constantly accompanied by the feeling that an unseen director would suddenly call “Cut,” and it would all come to a stop.

On the second morning I was growing more used to it. I bathed, and then with a sense that I was beginning to get the feel of the life, drifted to the Place, in search of an aperitif. I chose a café on the south side where a few trees shaded the tables, and wondered what to order. My usual drinks seemed out of key. A dusky, brightly saronged girl approached. On an impulse, and feeling like a character out of a very old novel I suggested a pernod. She took it as a matter of course.

“Un pernod? Certainement, monsieur,” she told me.

I sat there looking across the Square, less busy now that the dejeuner hour was close, wondering what Sydney and Rio, Adelaide and Sao Paulo had gained and lost since they had been the size of Lahua, and doubting the value of the gains whatever they might be…

The pernod arrived. I watched it cloud with water, and sipped it cautiously. An odd drink, scarcely calculated, I felt, to enhance the appetite. As I contemplated it a voice spoke from behind my right shoulder.

“An island product, but from the original recipe,” it said. “Quite safe, in moderation, I assure you.”

I turned in my chair. The speaker was seated at the next table; a well-built, compact, sandy-haired man, dressed in a spotless white suit, a panama hat with a colored band, and wearing a neatly trimmed, pointed beard. I guessed his age at about 34 though the gray eyes that met my own looked older, more experienced, and troubled.

“A taste that I have not had the opportunity to acquire,” I told him. He nodded.

“You won’t find it outside. In some ways we are a museum here, but little the worse, I think, for that.”

”One of the later Muses,” I suggested. “The Muse of Recent History. And very fascinating, too.”

I became aware that one or two men at tables within earshot were paying us — or, rather, me — some attention; their expressions were not unfriendly, but they showed what seemed to be traces of concern.

“It is—” my neighbor began to reply, and then broke off, cut short by a rumble in the sky.

I turned to see a slender white spire stabbing up into the blue overhead. Already, by the time the sound reached us, the rocket at its apex was too small to be visible. The man cocked an eye at it.

“Moon-shuttle,” he observed.

“They all sound and look alike to me,” I admitted.

“They wouldn’t if you were inside. The acceleration in that shuttle would spread you all over the floor — very thinly,” he said, and then went on: “We don’t often see strangers in Lahua. Perhaps you would care to give me the pleasure of your company for luncheon? My name, by the way, is George.”

I hesitated, and while I did I noticed over his shoulder an elderly man who moved his lips slightly as he gave me what was without doubt an encouraging nod. I decided to take a chance on it.

“That’s very kind of you. My name is David — David Myford, from Sydney,” I told him. But he made no amplification regarding himself, so I was left still wondering whether George was his forename, or his surname.

I moved to his table, and he lifted a hand to summon the girl.

“Unless you are averse to fish you must try the bouillabaisse— speciality de la maison,” he told me.

I was aware that I had gained the approval of the elderly man, and apparently of some others. The waitress, too, had an approving air. I wondered vaguely what was going on, and whether I had been let in for the town bore, to protect the rest.

“From Sydney,” he said reflectively. “It’s a long time since I saw Sydney. I don’t suppose I’d know it now.”

“It keeps on growing,” I admitted, “but Nature would always prevent you from confusing it with anywhere else.”

We went on chatting. The bouillabaisse arrived; and excellent it was. There were hunks of first-class bread, too, cut from those long loaves you see in pictures in old European books. I began to feel, with the help of the local wine, that a lot could be said for the twentieth-century way of living.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 7»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 7» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 7» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.