I could see no pursuers, but the humming noise waxed ever louder and I feared it without knowing why. I do not believe, Supremacy, that I would have felt so in the country of men; in the spirit land some enchantment draws away a warrior's blood, leaving a cold juice supporting life but not valor.

I was about to run again when I spied something glittering at my feet. It was a piece of red glass — such stuff as the priests use to form pictures in the windows of temples. It was broken and useless; yet before I could reflect on what I did I had snatched it up and thrust it among other such litter in a bag of knotted grass I had slung about my shoulders. I cannot tell why I did so foolish a thing or why I felt so vain about it, like a country wench with a new ribbon.

A night fog was coming up from the river now and filling the valleys. Though it brought forth foul odors from the soil at my feet, I blessed it, knowing it would conceal me.

The hills were lower and the fog thicker as I fled from valley to valley and I knew the river must be close by, but every breath burned in my chest and my steps stumbled. The roaring of the blood in my ears was so loud that I did not hear another running in the valley I crossed until he was nearly upon me. He was naked as I, and his long hair hung down in a filthy mat, but I would have kissed him as a brother had there been time, so happy was I to see a human face in that grim land.

He shouted to me — words I had never heard before, yet they were as clear to me as West Speech—“This way! You are lost. Follow me!”

He led me through a narrow crevice in the hills, which I had passed without seeing a moment before. On the other side the ground sloped cleanly down to the river and I could see the long white arch of a bridge that spanned it. We were almost upon it before I saw that it was the bridge of the troll, and then I knew fear indeed, and would have turned back had not my companion gripped me by the arm.

“A troll watches this bridge,” I said, but the clear words I formed in West Speech issued from my lips as guttural gruntings. He seemed to understand, however, and pointed to a low strong-house set almost at the water's edge.

“He is there, but he cares nothing for us. He is a sky watcher. See the Eye?”

I looked again and saw that there was a great eye of metal lace above the strong-house; it turned slowly as though it searched for something, hut its gaze was always toward the stars. Then the bridge was filled with light and the humming noise grew to a roar.

We ran faster than ever then; there was just time enough to get clear of the bridge and scramble up a little rise on the other side before they were upon us.

I halted there. We had run before them as vermin run; now I, at least, would stand as a man and a West Lands warrior should. My companion mewed with fright, but I heard laughter also and it was the fell laughter of trolls.

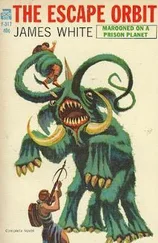

They were coming toward us faster than any beast could bear them, mounted on shining things which roared without pause and whose single eyes glared with.the yellow light I had seen. They halted at the foot of the knoll on which we stood and the roar of their mounts subsided to a murmur. The faces of trolls are not as the faces of men, yet I could see the triumph on every face and I recall thinking that thus the faces of men must look to a hunted beast who turns to make his stand.

One of the trolls dismounted then, and my gaze was drawn to him. He was larger than any forest devil and the muscles stood out under his skin and flickered as he moved. Had he been but a beast he would have been such as to chill the heart of the boldest hunter, but he was no mere animal. His eyes were of the yellow-green of seacoal fire and blazed more fiercely — level as a man's and filled with terrible wisdom. Strangely wrought weapons hung from his belt, and when I looked upon them, memories that were not mine came rushing into my mind, and I seemed to see naked men and women and children rent to pieces as if by thunderbolts.

By force of will I tore my gaze from them and looked about me lest I be taken from behind; and as I looked the other trolls seemed to fade and become less real, so that I knew they were but the creatures of his art where in truth only his spirit and mine stood alone.

I lifted my green stick as he came toward me. Jt was a mere wand still to my eyes, but it had an honest weight in my hand and light shone along the bark as though it were steel. Then in an instant all I saw was gone. I stood in the troll's den once more, swaying and grasping my true sword with a weak hand. The troll was before me still, older now, and bereft of the terrible weapons which had dangled from his belt before.

Then he laughed loud and deep, and I was again on the hillock. Scarce able to stand, I lashed his great arm with my wand and it snapped half off; as he grasped me the darkness closed upon me once more as it had on the bridge, but I struck him with the shattered stub of my stick until I knew no more.

When I woke again the troll's cave was better lit than when I had previously seen it, though light no longer rose from the pool. Instead a great brightness issued from a silver wand no longer than a man's finger which lay in the mud close to Dokerfins. I had. seen too much that day to fear anything however strange, and plucking it from the muck, I used its light to search out the hole.

My sword I found in Dokerfins' hand, it and he both drenched in the troll's dark blood; the grim mock-man himself lay not much farther off, all cut about with gaping wounds from which the blood no longer welled. At the first sight I thought it strange to see that the point had never told, but soon I understood all, as you, Supremacy, wiser than ever I, no doubt do now. For when Dokerfins awoke he was as one deep in drink or drug, babbling and unheeding. Then I knew that his body had but fought here the battle my own spirit had won from the troll in the spirit land, and his soul was scarce returned, alone and affrighted, to its proper place. That his untenanted husk could not use my sword's point was thus explained, for the sword's spirit was maimed when it broke in my hand.

From the pool's dimness I knew the day must be fast fading. It would be an evil venture to try to swim from that place in darkness, so taking the circlet the troll had worn and holding the mewing fay man as best I could I dived into the pool to free us or die, as might be. My spirit-broken blade I left to watch the troll rot; who would dare trust such a thing in war?

When I became aware again the sun was full in my face. Oh that blessed sun of Carson!

Can you understand what it meant to me to know I was no longer in that foul abscess under the riverbank? I will not bore you by describing the pleasure of the natives when they found us on the following day. My host — his name is Garth, have I mentioned that before? — had killed the traki in what he calls “a great spirit fight” which I take to mean that it was a sort of contest of wills as well as a physical battle, which with the traki I can well believe. Even knowing that the life of an intelligent being has been deliberately extinguished by him, I cannot feel the repulsion which perhaps I should, but it does somewhat disturb me that he seems to consider me a sort of squire or assistant in what he believes to have been a very creditable deed. At least it has given me useful prestige with the natives.

Now for the really amazing part of this adventure of mine. Garth brought back the metal circlet the traki had worn. When I examined it I found that the inscription on it is in characters similar to those found on Ceta II. The same is true of the carvings on the bridge. I thought the poor traki’s talk of a great city madness, and so it was, no doubt; but there exist shades of derangement. One is to believe in the reality of things wholly fictitious. Another, very characteristic of the old, is to hold in the mind’s present the shadows of the now-gone-forever. What might we not have learned from the traki had not Garth killed it?

Читать дальше