I was bending over him hoping to find signs of life when I heard the great roaring voice of the troll behind me; so loud and terrible was it that I wished to stop my ears against it. So that your Supremacy may know the troll’s speech I have instructed my scribe to write all his words large; thus your scribe shall apprehend to raise his voice in reading. This trick of clerkmanship I learnt of Dokerfins and like it well though my clerk thinks it gross and mechanical.

Then said he: “THAT ONE CANNOT AID YOU; YOU MUST FACE ME ALONE.”

And turning I beheld the troll, but not as I had seen him on the bridge. Here he glowed like the flame of a candle, so that every wrinkle could be seen in the dimness, and his form was that of a great Hunting-devil, but larger yet and higher above the eyes and wearing there a circlet of some metal. He had no sword nor other weapon, nor wore he armor.

I spoke to him boldly, saying, “I do not fear to face you, but rather think it strange that you who have neither blade nor byrnie should leave me my sword.”

“I CARE NOTHING FOR YOUR TOOL OR YOUR HARD SKIN — THEY WILL NOT HELP YOU IN THE HUNT WHICH IS TO COME. BUT FIRST TELL ME WHERE YOU FOUND YOUR COMPANION. HIS IS A STRANGE THOUGHT, OR SEEMED SO WHEN I TOUCHED IT ON THE BRIDGE TODAY.”

“He says he jell here from a star, if that moon-talk is aught to you. As to touching minds, I found the head of one whose mind you touched a moment past, but you do not seem to have done that to my friend yet.”

I confess, Supremacy, that I was surprised to hear myself speaking of the betattered Dokerfins as my friend, but I find the common occupancy of a troll's den breeds a strange feeling of comradeship.

“WHAT YOU CALL MOON-TALK MEANS MUCH TO ME. HE HAS BEEN BROUGHT FROM OUTWORLD TO THE GAMES IN OUR CITY; IT MAY BE THAT WHEN HE WAKES HE WILL SHOW SPORT. THOUGH I SHALL PERHAPS NEVER HAVE THE POWER OVER HIM I HOLD OVER YOU, YET HE SHALL AT LEAST SEE ME AS I WISH”

“I shall see you as I wish,” I told him, “and that is dead” And I drew forth my sword and came at him.

I never blade-reached him. Instead I found myself running breathless down a narrow valley with steep hills to either side. It was night, the air moist and cool in my lungs but smelling of smoke, as when water has been poured on a fire. My armor and all my raiment were gone; instead of my sword I held a length of green sapling, and was minded to toss it away when I noted it hung unnaturally heavy in my hand. Then I knew it was not I but my spirit running, and the sapling was my good sword in truth, though seeming not so in the spirit land; I suppose because it was a new-made blade and not my father's sword I bore.

I turned then to face whatever might come, but saw nothing and heard only a loud humming as of a swarm of flies. Mounted or afoot, it bodes best to hold the high ground, so I began to scramble up the bank on my left. In the gloom I had thought the hill to be of stones and earth in the common way, but the stones my feet kicked free sometimes clanged like iron or smashed with a noise like crockery. Often too my fingers felt ashes or cloth instead of grass. .

. . When I became aware of my surroundings again, my first thought was that the impact of the water on my eyes had resulted in blindness. It was several minutes before my pupils dilated enough for me to make out objects, and even then I could perceive only bulky shadows. The floor upon which I lay seemed to be of stone, covered with two inches of almost liquid mud. Even now, Professor Beatty, it humiliates me to recall it, but to set the record right let me admit that during my first few moments of consciousness I experienced nausea, a sort of dizziness or giddiness, and panic terror.

When I got myself under control I remembered my pocket illuminator and tried to get it out. My fingers were so swollen and weak that I could not unfasten the buttons of my shirt pocket. If you have ever tried to open a jackknife when your hands were nearly numb with cold you will know how I felt then.

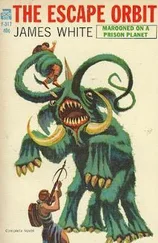

I was still fumbling with the pocket when a pool of water at the far end of the chamber in which I found myself heaved violently and a creature larger than a man emerged. This, as I learned later, was the traki. I will give you a detailed description of him before I close this letter, but for the present I am not going to let you see more of him than I did. All I knew was that the dank and stinking den in which I found myself had now been invaded by some huge creature, whether beast or nonhuman intelligence I had no way of knowing. I felt that I was about to die, to be killed with a horrible violence, and I could no longer turn away, as I have been in the habit of doing all my life, from the sickening thought of my mind’s termination and my body’s reduction to carrion.

All of us have encountered a telepathic adept at one time or another, but I certainly did not expect one here, nor had I ever before realized fully the enormous difference between communication with a human Talent and contact with one as alien as the traki. A Talent has always given me the impression that someone I could not otherwise sense was whispering in my ear while the supposed Talent sat passive some distance away. When the traki sent his signal it was as though a public-address system of enormous amplification and poor fidelity had been planted in the back of my skull, and when he received I felt myself an intelligent insect probed from above by some vast, corrupt intelligence.

“HOW DID YOU ESCAPE?”

The question boomed and screeched until I felt I must go mad. Intellectually I am quite convinced (though I know you are not in complete agreement) that our minds are merely protoplasmic computers of great sophistication — that we have no thought or life except that conferred by matter; yet I have never felt so much in sympathy with the so-called “liberal” cast of thought which holds otherwise as I did then. My body seemed a cast, an almost inert but painful prison from which the essential “I” struggled to escape, and while the essence of my being thus twisted to get away it forced my lips and larynx to say that it did not appear to me that I had escaped, and made my wooden fingers continue clawing at my pocket.

“IT IS WISE OF YOU TO KNOW THAT, WE WHO BROUGHT YOU HERE HOLD ALL THIS WORLD AND YOU CANNOT CROSS THE SEAS OF EMPTINESS AGAIN WITHOUT OUR AID.”

I was too busy at the moment to digest that rather cryptic statement. I had managed to open the pocket at last and was getting out my paralyzer and illuminator. As soon as I was able to fumble off the safety catch on the paralyzer, I lit up the cavern.

I promised you a good description of him earlier, Professor, but now I am not sure I can give you one without sounding like the author of a tenth-century bestiary, and no description can make you see him as I saw him, crouched in that dank chamber. Four limbs reminiscent of a gorilla’s arms, but hairless and shining black, were joined to a shapeless, swagbellied body. The head was more nearly human in appearance, a square face dominated by a great slit mouth like a catfish’s. The only clothing, if you can call it that, was a metal band covered with incised hieroglyphics which he wore about his head. I know this description must sound like that of an animal, but that was not the impression he gave. Rather I sensed a monstrous cunning, and most of all that he was old, and tainted with senility.

I had only time for the brief glimpse I have given you when the traki seemed to turn in upon himself and become something entirely different. It was as if the entire creature were one of those shapes topologists make which, when turned inside out, become totally unrecognizable. I am still not sure what it was I saw while this inversion was taking place (it lasted not more than half a second) but when it was complete the traki had become an elderly man in a white togalike robe. I hope this will not offend you, but his features had a noticeable resemblance to your own; in fact, during the conversation which followed, I sometimes found it difficult in spite of the painful nature of the thought contact to remember that it was not you to whom I spoke — a Professor Beatty who had grown a trifle strange, and more wise and powerful than I could ever hope to be.

Читать дальше