He opened the door. Feldman said, “Tomorrow, five, one hour. Okay?” Thornton looked back and nodded, and Feldman added, “Why did you put her down as the one mind that could exist with the Phalanx?”

He ate little dinner, and walked afterward. He hadn’t. He knew he hadn’t. He visualized the sheet of questions and his answers, and he knew that his memory would reproduce it faithfully for him. He hadn’t put her name down. The questions had all led to that one, of course: Can you name anyone who you think would qualify as a psycho-modular unit?

He had left it blank.

He saw it again in his mind, and it was blank.

He felt a stab of fear. What was Feldman after?

He wouldn’t recommend Paula, even if the thought had occurred to him. When Gregory died, eighteen years ago, she had written that crazy poem about the boy who chose death rather than killing. Gregory had died under enemy fire. He had mailed her the firing pin of his rifle, then had walked upright until he was felled. Stupid act of insanity. It had made all the papers, his death, and the bitter poetry that had flowed from Paula afterward. She was practically a traitor, as Gregory certainly had been. Again he wondered what Feldman was trying to do. He returned to his desk and worked until midnight.

He dreamed that night of the psycho-modular unit fixed in the island inside the house that was the Phalanx. It was a sealed tank that looked very much like an incubator, with rubber gloves built into it so that the operators could push their hands into them and handle the thing inside. There were six pairs of the gloves. To one side of the tank a screen, not activated now, had been placed to show electroencephalograph tracings. Thick clusters of wires led to desks close by, and on them were screens that showed chemical actions, enzymic changes, temperature of the nutrient solution and any fluctuations in its composition. Inside the tank were wires that ended in electrodes in the brain, the input and output wires, and they too were tapped so that men at desks could know exactly what was going in and out.

The Phalanx had been in steady operation for seven days and nights. The lights twinkled steadily, and in the back the EEG tracings were steady. The technicians had replaced the walls about the computer so that it was a house within a room, a tank within the house, a brain within the tank. There was still work to be done, still many programs to plan and translate and feed to the Phalanx, but any good programmer could do them now. They were talking about increasing the number of bugs to an even four dozen, and no one doubted that the computer could keep them all under control.

Thornton stood in the doorway looking at it for the last time. His work was done, his year over. Others would be interviewed now, or already had been, and they would feel the excitement coursing through them at the chance to work at the Institute for a year. He turned and left, picking up his bag at the main door. A car was outside to take him to the gate where Ethel would meet him. Feldman was on the steps waiting. He thrust a book into Thornton’s hand.

“A goodbye present,” he said. Thornton wondered if he had seen tears in the analyst’s eyes, and decided no. It had been the wind. The wind was blowing hard. He rode to the main gate, and when he left the car and walked through, he dropped the book. He got in his own car and drew Ethel to him.

“I was so afraid you’d be different,” she said after a moment. “I didn’t know what to expect after your year among geniuses. I thought you might not want to come out at all.” She laughed and squeezed his hand. “I am so proud of you! And you haven’t changed, not at all.”

He laughed with her. “You too,” he said. He wondered if there had always been that emptiness behind her eyes. She pressed on the accelerator and they sped down the road away from the Institute.

Behind them the wind riffled through the book until the guard noticed it lying in the dust and picked it up and tossed it in a trashcan.

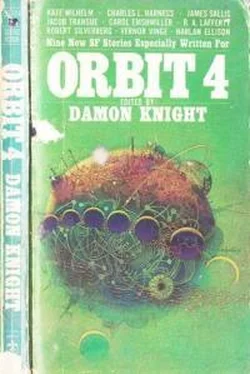

Charles L. Harness was born in 1915 in “an area of West Texas noted mostly for cactus, mesquite, and sandstorms. ” As a young man, while attending a theological seminary, he worked in a business establishment which happened to be located in the red-light district of Fort Worth, This stimulating double life ended, and he became a policeman in the identification bureau of the Fort Worth police department. “In this capacity I had the melancholy duty of fingerprinting many of my friends, both from the ‘ District ’ and from the Seminary. They were a lively lot, and did not seem to mind. ” Later, in Washington, D.C., he took a degree in chemistry, then another in law; married, and became a father.

He started writing in 1947 to clear up the obstetrical bills that followed his daughter's entrance into the world. He stopped, a few years later, “because she would stand in the hallway under my attic studio and cry for me to come down and play. ” When she left for college in 1964, he began writing again. Now a patent attorney for a large corporation, he lives in Maryland with his wife, daughter, and 13-year-old son.

Harness ’ s early stories—thirteen of them, including the novel Flight Into Yesterday and the short novel The Rose— were vanVogtian melodramas, exuberantly inventive, cracking with paranoid tension, intricately plotted. The new ones he has been producing since 1964 are more mature, more contemplative, more realistic in tone, but they are constructed in the same complex mosaic fashion. “Probable Cause" is about clairvoyance, the Constitution of the United States, thoughtography, the U.S. Supreme Court, feminine intuition, and the assassination of a President, among other things. Nobody but Harness could have woven all this into so symmetrical and satisfying a pattern—or made it mean so much.

PROBABLE CAUSE

By Charles L. Harness

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause . . .

Nor shall any person be compelled to be a witness against himself . . .

—Constitution of the United States, excerpts, Fourth and Fifth Amendments

Benjamin Edmonds turned the film advance knob on the self-developing camera in slow rhythmic motions of hand and wrist. When the mechanism locked, he placed the camera on its side next to the bronze casting on the wall table. He flipped off the ceiling light and turned on the faint red darkroom lamp over the developing trays. He sat for a moment, studying the casting and waiting for his eyes to adjust to the near darkness.

The replica was a plain, almost homely tiling: a hand clasping a piece of broomstick. Even after a century and a quarter it still radiated the immense strength and suprahuman compassion of its great model, and it would surely help to waken the distant sleeping shadows. Edmonds laid his own big hand over it softly; the metal seemed oddly warm.

It was time to begin.

He turned off the red light and let the blackness flow over him.

The images began almost immediately. At first they flickered vaguely, seemingly trapped within the plane of his eyelids. Then they gathered clarity and stereoscopic dimension, and moved out, and away. They were real, and he was there, in the crowded theater, looking up at the flag-draped presidential box, occupied by the three smaller figures and the tall bearded man in the rocking chair. And now, from behind, a fifth. The arm surely rising. The deadly glint of metal. The shot. The man leaping out of the box to the stage below. And pandemonium. Fluttering scenes. They were carrying the tall man across the street in the wavering paschal moonlight. And finally, in that far time, Edmonds permitted the strange hours to pass, until the right moment came, and the right image came.

Читать дальше