Stooping over him Argaven lifts up his hand, an old man’s hand, broad and hard, and starts to take from the forefinger the massive, carved gold ring. But he does not do it. “Let him keep it,” he says, “let him wear it.” For a moment he bends yet lower, as if he whispered in the dead man’s ear or laid his cheek against that rough, cold face. Then he straightens up, and stands awhile, and presently goes out through dark corridors, by windows bright with distant ruin, to set his house in order and begin his reign: Argaven, Winter’s king.

The Time Machine

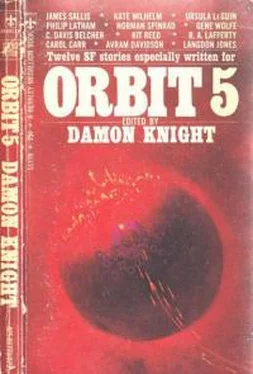

by Langdon Jones

The cell is not large. There is just room for a small bunk along one wall, and a small table on the other side, a stool in front of it. The table and the stool have once been painted a glossy red, but their finish has long been spoiled by time, and now light wood shows through the streaks of paint. The floor is flagged, and the walls are made of large blocks of stone. The stone has streaks of dampness across its surface, and in the air is a sweet smell of decay. There is a window high in the far wall, set with bars of rusted iron, and through it can be seen a patch of blue sky, and a wisp of yellow cloud. Sometimes, not very often, a bird flashes across the space like a brief hallucination. In the opposite wall there is a large metal door, with a grille set into its surface. Behind the grille is a shutter, so that those outside may, when they wish, observe the prisoner from a safe distance.

The bunk is made of metal, and is fixed permanently to one wall. It is painted green, and this color is interrupted only where the rusty nuts and bolts extrude. On one side the bunk is bolted to the wall, and on the other it is supported by two metal legs, which have worn little depressions in the stone floor. Above the bunk, crudely scratched into the wall, are various drawings and messages. There are initials, dates, obscenities and phallic drawings. Set a little apart from the others is the only one which does not make immediate sense. It is engraved deeply into the wall, and consists of two words, set one above the other. The engraving obviously took a great deal of time to complete. The upper of these words is “TIME,” the lower, “SOLID.”

The bunk is covered by rumpled grey blankets, which smell of the sweat of generations of prisoners. Sitting at the foot of the bunk is the prisoner. He is leaning over, his elbows on his knees, his back hunched, looking at a photograph in his hands.

The photograph is of a girl. It is just a little larger than two inches square, and is in black and white. It is a close-up, and the lower part of her arms, and her body below the waist are not revealed. Her head is not directly facing the camera, and she appears to be looking at something to one side, revealing a three-quarter view of her face. Behind her is a brick wall—a decorative wall in Holland Park on that day after the hotel and after the morning in the coffee shop; soon they were to part again at the railway station.

Her dark hair was drawn back, and she had a calm but emotional expression on her face. Her face was fairly round, but her high cheekbones caused a slight concavity of her cheeks, giving her always a slightly drawn look which he had always found immensely attractive, ever since he had first known her. Her features were somewhat negroid—“a touch of the tar brush, as my mother used to put it,” she had said in one of her letters—large dark eyes, and large lips which, when she smiled, gave her a look of ironic sadness. Occasionally she also had the practical look of a Northern housewife, and her energy was expressed in her face and her body. Her body was very slim, and her flesh felt like the flesh of no other woman on earth. When he had first seen her she had been wearing a black dress at a party, a dress which did nothing to conceal the smallness of her breasts, and which proudly proclaimed her slightness. This had captivated him immediately. It was something which accented her femininity, although doubtless she had not considered it in this way, and he saw her that first time as the most beautiful thing on earth.

He would meet her in Leicester. He would set off early on Sunday and take a train to Victoria, and walk among the few people about at this time on a Sunday morning to the coach station. He could never understand why it was— as he sat in the cafeteria with a cup of coffee—that the people all about appeared so ugly. The only people that morning who were at all pleasing to the eye were a family of Indians who had sat near him—the women in saris, and the men bewhiskered and proud in turbans. Perhaps it was all subjective, and everyone appeared ugly because he knew that this morning, in little more than three hours, he would be meeting her again. The weather was not impossibly cold—they wanted to make love, and many things were against it that week. At nine-fifteen he would walk over, past the coaches for Lympne airport and France, to the far corner of the yard, where the Leicester coach would be waiting.

He got in the coach. There were never more than eight or nine people who wanted to go to Leicester early on a Sunday morning, and he would walk down to the back of the coach and sit on the left-hand side. Why always the left, he didn’t know. At nine thirty-five the vehicle would set off, pouring out clouds of diesel smoke, emerging from its home like a mechanical dragon. As they passed Marble Arch, Swiss Cottage, and headed for the Ml, he was conscious of a mounting tension. Partly sexual— partly the knowledge that soon he would see her again, and partly because he knew that he knew. What was going to happen this time? He could visualize that one morning she wouldn’t come, but he would, and instead of loving there would be hatred and fighting. She had told him during the week, and he had been very upset. But he wanted her to continue, for he knew what it would do to her to have to stop now. What had been set into action was a series of circumstances that had to run a certain course until it was possible to break it. And the breaking would be hard—was hard.

The sun was shining, and the fields that they passed became transformed, as they always did, by her proximity in time. Everything around him was beautiful. It was as if he could see the scene through the coach window with an intensity that would not be possible normally. It was as if together they were one being, and that apart from her he was less than half a person. But there were four other people who depended on her as well. Two little boys, one little girl and one adult man. A family is a complete entity as well. Later he would go to her home in West Cutford, and see her with her children, and feel himself to be a malevolent force, a wildly destructive element; that didn’t belong here, and yet, seeing at the same time an image of what might have been; how close was this reality to the one he wanted.

When the coach left the motorway, it was only half an hour before he would be in Leicester, and three quarters before they would be together, their proximity having an astronomical rightness, as implacably correct as the orbit of the earth. The watery January sun shone onto the brown brick buildings that told him that soon he would be at their meeting-place—the coach station in Southgate Street. This place had a special significance for him; it was like the scene of some great historical event. But most of the places were; not the hotel, where the coming and going of other people obscured the significance of their own, but their little shed at Groby Pond, their room at the top of a house in West London. All these places deserved some kind of immortality.

Now the tension was very strong; his muscles were clenched all over his body and his hands were shaking. The coach approached some traffic lights, turned left, bumping over a rough road surface, and went down a grim street, full of half-demolished buildings. Further down were some other buildings composed of reddish-brown brick, except for a modem pub which was opposite a large flat area surrounded by metal railings. The coach turned into tills concrete area, for this was Southgate Street. As the coach slowed up the few people inside began to rise, putting on overcoats and collecting their luggage. He looked intently through the windows to see if she had arrived. She wasn’t here yet. The coach was early; it was only quarter-past twelve. There was six and a half hours of the day left. This was always the most difficult part. Before he had felt that he was going toward her; that he could feel the distance between them lessening. But now all the movement was up to her and he could no longer be directly aware of it.

Читать дальше