My son-in-law chuckles and his top lip really goes crazy. “Oh, were you surprised? Imported meats aren’t a rarity here, you know. Just the other day one of my clients was telling me about an all-Earth meal he had at home.”

“Your client?” Sadie asks. “You wouldn’t happen to be a lawyer?” (My wife amazes me with her instant familiarity. She could live with a tyrannosaurus in perfect harmony. First she faints, and while she’s out cold everything in her head that was strange becomes ordinary and she wakes up a new woman.)

“No, Mrs. Trumbnick. I’m a—”

“—rabbi, of course,” she finishes. “I knew it.The minute Hector found that skullcap I knew it. Him and his riddles. A skullcap is a skullcap and nobody not Jewish would dare wear one—not even a Martian.” She bites her lip but recovers like a pro. “I’ll bet you were out on a Bar Mitzvah—right?”

“No, as a matter of fact—”

“—a Bris. I knew it.”

She’s rubbing her hands together and beaming at him. “A Bris, how nice. But why didn’t you tell us, Lorinda? Why would you keep such a thing a secret?”

Lorinda comes over to me and kisses me on the cheek, and I wish she wouldn’t because I’m feeling myself go soft and I don’t want to show it.

“Mor isn’t just a rabbi, Daddy. He converted because of me and then found there was a demand among the colonists. But he’s never given up his own beliefs, and part of his job is to minister to the Kopchopees who camp outside the village. That’s where he was earlier, conducting a Kopchopee menopausal rite.”

“A what!”

“Look, to each his own,” says my wife with the open mind. But me, I want facts, and this is getting more bizarre by the minute.

“Kopchopee. He’s a Kopchopee priest to his own race and a rabbi to ours, and that’s how he makes his living? You don’t feel there’s a contradiction between the two, Morton?”

“That’s right. They both pray to a strong silent god, in different ways of course. The way my race worships, for instance—”

“Listen, it takes all kinds,” says Sadie.

“And the baby, whatever it turns out to be—will it be a Choptapi or a Jew?”

“Jew, shmoo,” Sadie says with a wave of dismissal. “All of a sudden it’s Hector the Pious—such a megilla out of a molehill.” She turns away from me and addresses herself to the others, like I’ve just become invisible. “He hasn’t seen the inside of a synagogue since we got married—what a rain that night—and now he can’t take his shoes off in a house until he knows its race, color and creed.” With a face full of fury, she brings me back into her sight. “Nudnick. what’s got into you?”

I stand up straight to preserve my dignity. “If you’ll excuse me, my things are getting wrinkled in the suitcase.”

Sitting on my bed (with my shoes on), I must admit I’m feeling a little different. Not that Sadie made me change my mind. Far from it; for many years now her voice is the white sound that lets me think my own thoughts. But what I’m realizing more and more is that in a situation like this a girl needs her father, and what kind of a man is it who can’t sacrifice his personal feelings for his only daughter? When she was going out with Herbie the Hemopheliac and came home crying it had to end because she was afraid to touch him, he might bleed, didn’t I say pack your things, we’re going to Grossingers Venus for three weeks? When my twin brother Max went into kitchen sinks, who was it that helped him out at only four per cent? Always, I stood ready to help my family. And if Lorinda ever needed me, it’s now when she’s pregnant by some religious maniac. Okay—he makes me retch, so I’ll talk to him with a tissue over my mouth. After all, in a world that’s getting smaller all the time, it’s people like me who have to be bigger to make up for it, no?

I go back to the living room and extend my hand to my son-in-law the cauliflower. (Feh.)

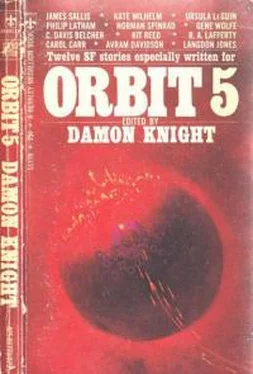

Winter's King

by Ursula K. LeGuin.

When whirlpools appear in the onward run of time and history seems to swirl around a snag, as in the curious matter of the Succession of Karhide, then pictures come in handy: snapshots, which may be taken up and matched to compare the young king to the old king, the father to the son, and which may also be rearranged and shuffled till the years run straight. For despite the tricks played by instantaneous interstellar communication and just-sub-lightspeed interstellar travel, time (as the Plenipotentiary Axt remarked) does not reverse itself; nor is death mocked.

Thus, although the best-known picture is that dark image of a young man standing above an old one who lies dead in a corridor lit only by mirror-reflections in vague alcoves of a burning city, set it aside a while. Look first at the young king, the pride of his people, as bright and fortunate a man as ever lived to twenty-two; but when this picture was taken he had his back against a wall. He was filthy, he was trembling, and his face was blank and mad, for he had lost that minimal confidence in the world which is called sanity. Inside his head he repeated, as he had been repeating for hours or years, over and over, “I will abdicate. I will abdicate. I will abdicate.” Inside his eyes he saw the red-walled rooms of the Palace, the towers and streets of Erhenrang in falling snow, the lovely plains of the West Fall, the white summits of the Kargav, and he renounced them all. “I will abdicate,” he said not aloud and then, aloud, screamed as once again the man dressed in red and white approached him saying, “Sir! a plot against your life has been discovered in the Artisan School,” and the humming noise began again, softly. He hid his head in his arms and whispered, “Stop it, stop it,” but the humming whine grew higher and louder and nearer, relentless, until it was so high and loud that it entered his flesh, tore the nerves from their channels and made his bones dance and jangle, hopping to its time. He hopped and twitched, bare bones strung on thin white threads, and wept dry tears, and shouted, “Have them— Have them— They must— Executed— Stopped— Stop!”

It stopped.

He fell in a clattering chattering heap to the floor. What floor? Not red tiles, not parquetry, not urine-stained cement, but the wood floor of the room in the tower, the tower room where he was safe, safe from the old, mad, terrible man, the king, his father. In shadows there he hid away from the voice and from the great, gripping hand that wore the Sign-Ring. But there was no hiding, no safety, no shadow. The man dressed in black had come even here and had hold of his head, lifted it up, lifted on thin white strings the eyelids he tried to close.

“Who am I? Who am I?”

The blank black mask stared down, and the young king struggled, sobbing, because now the suffocation would begin: he would not be able to breathe until he gasped out the name, the right name—“Gerer!”— He could breathe. He was allowed to breathe, he had recognized the black one in time. “Who am I?” said a different voice, gently, and the young king groped for that strong presence that always brought him sleep, truce, solace. “Rebade,” he whispered, “oh God! tell me what to do. ...”

“Sleep.”

He obeyed. A deep sleep and dreamless, for it was real: in reality he was dead. Dreams came at waking, now. Unreal, the horrible dry red light of sunset burned his eyes open and he stood, once more, on the Palace balcony looking down at fifty thousand black pits opening and shutting. From the pits came a paroxysmic gush of sound again and again, a shrill rhythmic eructation: his name. His name was screamed in his ears as a taunt, as a jeer. He beat his hands on the narrow brass railing and shouted to them, “I will silence you!” He could not hear his voice, only their voice, the pestilent mouths of the mob that feared and hated him, screaming his name. —“Come away, my lord,” said the one gentle voice, and Rebade drew him away from the balcony into the vast, red-walled quiet of the Hall of Audience. The screaming ceased as if a machine had been switched off. Rebade's look was as always composed, compassionate. “What will you do now?” he asked.

Читать дальше