I catch the wires attached to Sid and pull them loose, half pull him from the bed, and we end up in a heap. He holds me tightly for a long time, until we are both breathing normally again, and my . shaking has stopped, and his too.

There is pale dawnlight in the room. Enough to see that his dark hair is damp with sweat, and curly on his forehead. He pushes it back and very gently moves me aside and disentangles himself from the wires.

“We have to get out of here,” he says.

Staunton is sound asleep on the couch, breathing deeply but normally, and Roger is also sleeping. His graph shows that he has had nightmares several times.

We take our coffee into the room where Sid slept, and sit at the window drinking it, watching morning come to Somerset. I say, “They don’t know, do they?”

“Of course not.”

Poor Haddie appears at the far end of the street, walking toward Mr. Larson’s store. He shuffles his feet as he moves, never lifting them more than an inch. I shudder and turn away.

“Isn’t there something that we should do? Report this, or something?”

“Who would believe it? Staunton doesn’t, and he has seen it over and over this week.”

A door closes below us and I know Dorothea is up now, in the kitchen starting coffee. “I was in her dream, I think,” I say.

I look down into my cup and think of the retirement villages all over the south, and again I shiver. “They seem so accepting, so at peace with themselves, just waiting for the end.” I shake the last half inch of coffee back and forth. I ask, “Is that what happened with me? Did I not want to wake up?”

Sid nods. “I was taking the electrodes off your eyes when you snapped out of it, but yours wasn’t a nightmare. It just wouldn’t end. That’s what frightened me, that it wasn’t a nightmare. You didn’t seem to be struggling against it at all. I wonder what brought you out of it this time.”

I remember the gleaming ice sculpture, the boy with curly hair who will be gone so soon, and I know why I fought to get away. Someday I think probably I’ll tell him, but not now, not so soon. The sun is high and the streets are bright now. I stand up. “I’m sorry that I forgot to turn on the tape recorder and ask you right away what the dream was. Do you remember it now?”

He hesitates only a moment and then shakes his head. Maybe someday he’ll tell me, but not now, not so soon.

I leave him and find Dorothea waiting for me in the parlor. She draws me inside and shuts the door and takes a deep breath. “Janet, I am telling you that you must not bring your father back here to stay. It would be the worst possible thing for you to do.”

I can’t speak for a moment, but I hug her, and try not to see her etched face and the white hair, but to see her as she was when she was still in long skirts, with pretty pink cheeks and sparkling eyes. I can’t manage it. “I know,” I say finally. “I know.”

Walking home again, hot in the sunlight, listening to the rustlings of Somerset, imagining the unseen life that flits here and there out of my line of vision, wondering if memories can become tangible, live a life of their own. I will pack, I think, and later in the day drive back up the mountain, back to the city, but not back to my job. Not back to administering death, even temporary death. Perhaps I shall go into psychiatry, or research psychology. As I begin to pack, my house stirs with movement.

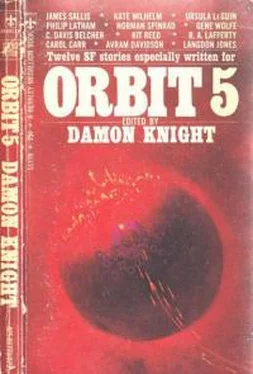

The Roads, The Roads, The Beautiful Roads

by Avram Davidson

The rumor that the already controversial new doublespeed thruway would be closed to motorcycles was just that: a rumor: and it had already been officially denied —twice. Craig Burns thought now that perhaps it had been a mistake to deny it at all. Gave the rumor dignity ... his mind absently sought a better word as he slipped through the milling crowd (crowd? almost a mob) on the steps and in the corridors of the new State Capital Building. Currency! That was the word.

. . . gave the rumor currency . . .

Because, besides the usual knots of little old ladies with their Trees, Yes! Thruway, No! buttons, besides the inevitable delegations of hayseeds from Nowhere Flats who were either complaining that the thruway was scheduled to go too near their town or complaining that it wasn’t scheduled to go near enough, besides the representatives of the rival guild—the urban planners—with their other ideas and their briefcases and their indoor-pale skins (so different from the ruddy glow or tan of a real out-in-all-weather man; besides all these (and including as always some Hire More Minority protesters), today it seemed as though all the motorcycle freaks in the state were on hand. On hand, and out for blood. Well, well, what the hell. It added a little color to the scene. And wouldn’t make any difference at all, in the end: Gypsy Jokers with long hair, Hell’s Angels who were merely shaggy, Brave Bulls in their Viking-horned crash helmets, and the Gentlemen of the Road, so super-groomed and—

With the blank face and absent-minded slouch he had learned to be the best thing for slipping through angry crowds, Craig managed to get almost to the door of the Committee Room without being recognized. And even then, with a pleasant smile, he succeeded in getting inside before the reporters and cameramen got to him. With an apologetic gesture. No point in antagonizing Media, generally so helpful in picking out and publicizing the more outstanding of the anti-highways people and thus showing them up for the nuts and oddballs that they really were. But it made little sense to stop in the middle of them just to grant an on-the-spot interview.

In fact, Burns thought, taking one last look, head half-turned, it made no sense at all.

Horns on their crash helmets, for God’s sake!

Just as some composers never tire of playing their own music, so Craig Burns never tired of driving over the beautiful highways he . . . well ... he and his Department . . . had created. It had been a labor of love building them, seeing each one through from the preliminary survey through actual construction to the time he liked best of all. When the roads were ready to go but not yet open to the public. When he could drive along and drive alone for miles . . . and miles . . . sometimes for hundreds of miles. Just Highway Chief Craig Burns and his car and his beautiful roads, with their lovely and intricate bypasses and cloverleafs and underpasses, slow and steady when he felt like it, revving it up and gauging the niceties of the straight stretches or the delightfully calculated curves when he felt like it. Over and under and around and across and back and under and—

—nobody on the whole highway but him.

It was better than a woman. It was better even than the power of office. It was just about the best thing there was.

Sometimes, smiling to himself, he wondered if he really didn't sometimes push through new road plans just for the sheer pleasure of this, even if the new roads weren’t really needed. But the smile was for the joke, the secret, private little joke, for there was really no such thing as a new road which wasn’t needed. And as for the things which weren’t so nice ... the stupid, stupid, jackass things which people did with the beautiful roads . . . crowding and packing and jamming them with their cars and trucks and motorcycles and station wagons . . . stupid people, stupid jerks, jackasses!—so that all kinds of things had to be done, afterwards, to the sweet and clean and lovely new roads—

As for that, Craig didn’t care to think about that, much. It made him get that hot feeling in the skin of his face, that surging, raging feeling around his heart. That sort of thing, he left mostly to the others in the Department. And everybody else in the Department was the others. He’d created. Let them mar it, since it had to be marred. Changing routes, adding, subtracting, closing down, chopping and changing—let them do it. It wasn’t his fault.

Читать дальше