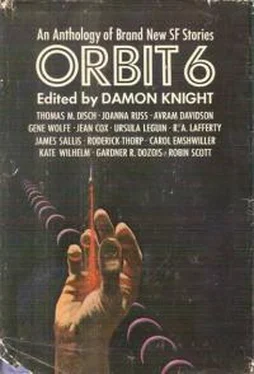

Дэймон Найт - Orbit 6

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Дэймон Найт - Orbit 6» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1970, Издательство: G. P. Putnam's Sons, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Orbit 6

- Автор:

- Издательство:G. P. Putnam's Sons

- Жанр:

- Год:1970

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Orbit 6: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Orbit 6»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Orbit 6 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Orbit 6», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘It is you who must say it first.’

‘I think,’ I would say, ‘that you are a Morlock,’ and sitting on the bed in my mother’s rented room with The Time Machine open beside her, she would say:

‘You are exactly right. I am a Morlock. I am a Morlock on vacation. I have come from the last Morlock meeting, which is held out between the stars in a big goldfish bowl, so all the Morlocks have to cling to the inside walls like a flock of black bats, some right side up, some upside down, for there is no up and down there, clinging like a flock of black crows, like a chestnut burr turned inside out. There are half a thousand Morlocks and we rule the worlds. My black uniform is in the wardrobe.’

‘I knew I was right,’ I would say.

‘You are always right,’ she would say, ‘and you know the rest of it too. You know what murderers we are and how terribly we live. We are waiting for the big bang when everything falls over and even the Morlocks will be destroyed; meanwhile I stay here waiting for the signal and I leave messages clipped to the frame of your mother’s amateur oil painting of Main Street because it will be in a museum some day and my friends can find it; meanwhile I read The Time Machine.’

Then I would say, ‘Can I come with you?’ leaning against the door.

‘Without you,’ she would say gravely, ‘all is lost,’ and taking out from the wardrobe a black dress glittering with stars and a pair of silver sandals with high heels, she would say, ‘These are yours. They were my great-grandmother’s, who founded the Order. In the name of Trans-Temporal Military Authority.’ And I would put them on.

It was almost a pity she was not really there.

Every year in the middle of August the Country Club gave a dance, not just for the rich families who were members but also for the ‘nice’ people who lived in frame houses in town and even for some of the smart, economical young couples who lived in apartments, just as if they had been in the city. There was one new, red-brick apartment building downtown, four storeys high, with a courtyard. We were supposed to go, because I was old enough that year, but the day before the dance my father became ill with pains in his left side and my mother had to stay home to take care of him. He was propped up on pillows on the living room daybed, which we had pulled out into the room so he could watch what my mother was doing with the garden out back and call to her once in a while through the windows. He could also see the walk leading up to the front door. He kept insisting that she was doing things all wrong. I did not even ask if I could go to the dance alone. My father said:

‘Why don’t you go out and help your mother?’

‘She doesn’t want me to,’ I said. ‘I’m supposed to stay here,’ and then he shouted angrily, ‘Bess! Bess!’ and began to give her instructions through the window. I saw another pair of hands appear in the window next to my mother’s and then our guest — squatting back on her heels and smoking a cigarette — pulling up weeds. She was working quickly and efficiently, the cigarette between her teeth. ‘No, not that way!’ shouted my father, pulling on the blanket that my mother had put over him. ‘Don’t you know what you’re doing! Bess, you’re ruining everything! Stop it! Do it right!’ My mother looked bewildered and upset; she passed out of the window and our visitor took her place; she waved to my father and he subsided, pulling the blanket up around his neck. ‘I don’t like women who smoke,’ he muttered irritably. I slipped out through the kitchen.

My father’s toolshed and working space took up the farther half of the back yard; the garden was spread over the nearer half, part kitchen garden, part flowers, and then extended down either side of the house where we had fifteen feet or so of space before a white slat fence and the next people’s side yard. It was an on-and-offish garden, and the house was beginning to need paint. My mother was working in the kitchen garden, kneeling. Our guest was standing, pruning the lilac trees, still smoking. I said:

‘Mother, can’t I go, can’t I go !’ in a low voice.

My mother passed her hand over her forehead and called ‘Yes, Ben!’ to my father.

‘Why can’t I go!’ I whispered. ‘Ruth’s mother and Betty’s mother will be there. Why couldn’t you call Ruth’s mother and Betty’s mother?’

‘Not that way!’ came a blast from the living room window. My mother sighed briefly and then smiled a cheerful smile. ‘Yes, Ben!’ she called brightly. ‘I’m listening.’ My father began to give some more instructions.

‘Mother,’ I said desperately, ‘why couldn’t you —’

‘Your father wouldn’t approve,’ she said, and again she produced a bright smile and called encouragingly to my father. I wandered over to the lilac trees where our visitor, in her usual nondescript black dress, was piling the dead wood under the tree. She took a last puff on her cigarette, holding it between thumb and forefinger, then ground it out in the grass and picked up in both arms the entire lot of dead wood. She carried it over to the fence and dumped it.

‘My father says you shouldn’t prune trees in August,’ I blurted suddenly.

‘Oh?’ she said.

‘It hurts them,’ I whispered.

‘Oh,’ she said. She had on gardening gloves, though much too small; she picked up the pruning shears and began snipping again through inch-thick trunks and dead branches that snapped explosively when they broke and whipped out at your face. She was efficient and very quick.

I said nothing at all, only watched her face.

She shook her head decisively.

‘But Ruth’s mother and Betty’s mother —’ I began, faltering.

‘I never go out,’ she said.

‘You needn’t stay,’ I said, placating.

‘Never,’ she said. ‘Never at all,’ and snapping free a particularly large, dead, silvery branch from the lilac tree, she put it in my arms. She stood there looking at me and her look was suddenly very severe, very unpleasant, something foreign, like the look of somebody who had seen people go off to battle to die, the ‘movies’ look but hard, hard as nails. I knew I wouldn’t get to go anywhere. I thought she might have seen battles in the Great War, maybe even been in some of it. I said, although I could barely speak:

‘Were you in the Great War?’

‘Which great war?’ said our visitor. Then she said, ‘No, I never go out,’ and returned to scissoring the trees.

On the night of the dance my mother told me to get dressed, and I did. There was a mirror on the back of my door, but the window was better; it softened everything; it hung me out in the middle of a black space and made my eyes into mysterious shadows. I was wearing pink organdy and a bunch of daisies from the garden, not the wild kind. I came downstairs and found our visitor waiting for me at the bottom: tall, bare-armed, almost beautiful, for she’d done something to her impossible hair and the rusty reddish black curled slickly like the best photographs. Then she moved and I thought she was altogether beautiful, all black and rippling silver like a Paris dress or better still, a New York dress, with a silver band around her forehead like an Indian princess’s and silver shoes with the chunky heels and the one strap over the instep.

She said, ‘Ah! don’t you look nice,’ and then in a whisper, taking my arm and looking down at me with curious gentleness, ‘I’m going to be a bad chaperon. I’m going to disappear.’

‘Well!’ said I, inwardly shaking, ‘I hope I can take care of myself, I should think.’ But I hoped she wouldn’t leave me alone and I hoped that no one would laugh at her. She was really incredibly tall.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Orbit 6»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Orbit 6» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Orbit 6» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.