Did you talk to Simon about this?

My feet waved in the air below me. Yes.

She sat back in her seat and the pedals of the bike drifted slowly forward. That was a cruel thing to do.

Can we install the antenna or not?

It’s a waste of time.

You’re wrong.

I waited for her to round on me then, to tell me off. She’d done it before, when we disagreed about the fastest method to unload a shipment or the best way to fix a piece of equipment.

But she didn’t. She turned back to the porthole, gripped the handlebars of the bike tighter, and sped up. The only fuel cells that could carry an explorer that far failed, she said. And we don’t know why.

We could find out—

We tried. We were all on the Pink Planet for months—me, Simon, James, and Theresa. Taking the fuel cell apart and putting it back together, hoping the rescue mission could be salvaged. James and Theresa are still there. It’s driven them half mad and they still don’t have an answer.

My stomach pressed against my skin. I didn’t know that.

There’s no way to reach the Inquiry crew. If they’re alive—a little shudder moved through her body—all we can hope for is that they figure out how to save themselves.

Amelia wouldn’t talk to me about it anymore that day. But I didn’t care. They were alive. I couldn’t know that and do nothing; I couldn’t know that and sit still. The sound—the rush of air, the high pops—was always with me now, which meant the Inquiry crew were always with me too. When the question of how we would get to them—and whether we could do it in time—came into my mind, I told myself, One thing at a time.

Then Simon discovered a leak in his suit, and the plan for the spacewalk changed. We couldn’t wait to repair the gyroscope because it was essential to keeping the station from slipping out of orbit. Rachel had to operate the robotic arm to deliver the new rotor for the failing gyroscope. So the spacewalk would have to be performed by Amelia and me.

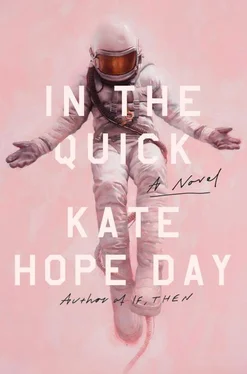

In the airlock Amelia and I got into our suits. It had been weeks since I’d been in a suit and I struggled to push my limbs inside. My body was different inside its white layers, had expanded in some places and shrunk in others. My torso felt wobbly, but that was nerves. I’d already stowed an antenna in an outer compartment of my suit. I planned to install it next to the urine processing vent if given the opportunity. I hadn’t told anyone; I had hidden it that morning when I was doing systems checks alone.

I locked my helmet. Amelia tested the seals on our suits by raising the pressure inside the airlock, and we checked and rechecked our oxygen tanks. Together we opened the egress hatch and sparkling dust burst from the station. Small bolts and screws and a pencil bumped along the lock’s walls and wafted away. We blinked in the blinding sunlight.

Amelia pulled out a platform with foot restraints attached to it, and we transferred our tether cord clips from inside to outside and secured our boots. Then we let go and our arms floated and our tethers waved behind us like long tails. It felt as if we weren’t moving, as if the station stood still, even though we were speeding at eighteen thousand miles per hour around the Earth. There was complete silence. No wind. No vibration, despite everything going on inside the station’s walls, all its fans and pipes and wires.

Amelia talked into her radio, We’re proceeding aftward to the gyroscope panel.

Rachel’s voice sounded in our helmets, Roger that.

We pulled ourselves along on the handrails and navigated over and around jutting trusses, equipment, and antennae to the gyroscope compartment at the stern side of the station. When we reached the gray box we strapped our feet to the restraints below it. The Earth was gigantic ahead of us and its blues and greens and whites pressed hard against my eyes.

Amelia retrieved a screwdriver from her tool belt and began to slowly unscrew the compartment’s outer panel, and then its inner panel. Each screw she carefully placed inside her belt. We’re going to rotate the interior tray to access the R3 gyroscope, she told Rachel.

Okay. I’m going to start moving the arm into position.

Amelia positioned herself on one side of the tray, and I did on the other. The sun was behind us now and the station shined brilliantly like sun on water. Through my gloves I felt the heat of my handrail, like the handle of a pot left on the stove too long. We turned the tray, and then pulled it halfway out of its compartment. I pushed my body inside, opened the R3 gyroscope, and began to unscrew the malfunctioning rotor. Above Amelia’s head the arm inched toward us.

We had practiced the steps of the repair two times inside, but in our bulky suits each action took three times as long and the job was less a series of steps than a kind of halting slow-motion dance. We usually worked well together. But today was different. Amelia handed me tools before I was ready; our helmets knocked against each other as we reached into the compartment at the same time.

I’m in position, Rachel said. Are you ready?

Not even close, Amelia said. Our shoulders bumped and her wrench slipped from her hand and wobbled away—and then snapped back on its tether. Would you move? she said to me.

I’m doing exactly what we did inside, I said.

No, you’re not. You’re off.

So are you.

Whose fault is that?

How is it my fault—

Amelia switched her radio to the two-way channel so only I could hear.

I don’t want to think about them, she said. If I’m thinking about them, I can’t do my job.

The Inquiry crew.

Yes.

The Earth slid past us; a storm swirled off the coast of Africa.

If they’re alive don’t you want to know? I asked.

Your bed was next to Carla’s your first year at Peter Reed, she said.

Yes.

Anu’s was next to mine.

The array behind her helmet sparked and flared.

She was so smart, Amelia said. And strong. She built the communications system on Inquiry. If she were alive we’d know it.

She switched back to the three-way channel. We worked silently: detached the new rotor from the robotic arm, slid it into place, and slowly tightened it. The angle was awkward and Amelia’s wrench could move only a quarter rotation at a time. I took a turn; we went back and forth until it was finally secure.

We’re nearing the two-hour mark, Rachel said.

I want to look at the other gyroscopes, Amelia said. If their rotors are degrading like R3’s did—

Save it for the next spacewalk.

If we need to ask for another rotor in the next packet I want to know now.

Fine. But do it fast.

We entered the Earth’s shadow and turned on our headlamps. The irregular shapes of the station shined darkly in the cool light of the moon, its arrays glinting silver in the deep black. From where we were I could see the length of its starboard and the panel that contained the urine processor vent.

June. Rachel’s voice came through my radio. There’s a loose panel near the hatch. If you’re staying out there I want you to take a look.

Amelia motioned. Go ahead. I can do this myself.

The urine processor vent was only a yard farther starboard than the loose panel, and I thought, I can do both. It would be the work of only a few minutes. I pulled myself from handrail to handrail, navigating around equipment, fighting the drift of my legs and feet. I began to sweat. I halved the distance to the panel and then my tether pulled taut. It wasn’t going to reach. I turned, crawled back, and hastily moved my tether clip.

The vent was inconspicuous among all the other jutting and shining equipment on the starboard side of the station. But I knew exactly what to look for.

Читать дальше