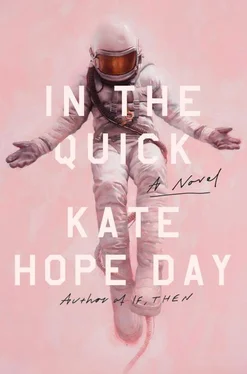

Kate Hope Day

IN THE QUICK

QUICK, adj.

Moving at a high speed: as quick as lightning

Fast in understanding, thinking, or learning. Mentally agile: a quick mind

Reacting to stimuli immediately and intensely: quick-tempered

QUICK, n.

Characterized by the presence of life. Living persons: the quick and the dead

The tender flesh of the living body, esp. under the nails: nails bitten down to the quick

Informally, as by astronauts: the final minutes of life before total oxygen deprivation: in the quick

Space is cruel to the human body. We aren’t machines, rockets with metal skin and polymer bones, rovers with microchips for guts. Our bodies are full of fluid and soft tissue. We aren’t built for space. Our thoughts, the things we know, are sturdier in zero gravity, but they originate in gray matter. They change shape, even disappear in the face of disorientation, dehydration, oxygen deprivation. Because ideas require bodies too, hands, lips, a tongue, ears. Otherwise they’re about as useful as dust motes drifting in the air.

When I was twelve years old and watched test rockets spark through the sky outside my aunt Regina’s house, I imagined their destinations—perfectly round planets colored red and pink and white. I pictured spacesuits, puffy and bright against a black expanse. It didn’t occur to me to think about the bodies inside those suits, the brains inside those helmets.

Not until a frozen day in November when the news came that the Inquiry explorer was in trouble. It was on a six-year mission, the first of its kind, to travel farther in our solar system than any manned mission had gone before. Inquiry was special; more than a decade of research at the National Space Program had gone into building the explorer, and it was manned by four of the most talented astronauts in the world.

It was a Saturday, late morning. I sat in the window seat in the living room with a book on my lap: New History of Energy. A chapter was devoted to my uncle and his famous fuel cell. The book smelled like him—like metal shavings and pen ink. Since he’d died I’d read the chapter at least twenty times.

I turned a page. Outside, rockets launched from the NSP campus lit up the hard gray sky. The sound of the TV came from the living room; a man was talking about Inquiry. I went into the hallway to listen and my limbs went cold. The explorer had lost all propulsion control just as it was beginning its orbit around Saturn.

The newscaster lowered his voice and began talking about the minutes leading up to when the explorer lost power. He said its fuel cells were suspected. But that couldn’t be right because my uncle had invented those cells. I moved closer, my stomach a heavy weight. He didn’t say anything more about the cells. Instead he talked about the Inquiry crew, and I grew impatient because I already knew everything about them, where they grew up, how old they were, what they had studied in school. If they had siblings and how many. Their hobbies and what they liked to read—I could tell you every detail.

The newscaster began reading from a statement issued from NSP. They were in constant communication with Inquiry, it said, and were working around the clock to troubleshoot the suspected fuel cell malfunction. Inquiry had recently received an unmanned supply capsule, the second of twelve scheduled to reach it at six-month intervals, and had ample food and water and an open line of communication with Earth. NSP was confident a solution was imminent. The crew were not in any immediate danger and had been in contact with their families. Then the man stopped talking about Inquiry and the weather report came on.

I returned to my spot in the window and called the dogs, Reacher and Duster, to come sit with me, but neither came. I felt chilled and stiff, and pulled my sweater to my chin. The words in New History of Energy swam on the page. I got up, went into the kitchen, and opened the closet door.

Inside was my aunt’s new vacuum, a sleek silver machine with a nozzle like a two-headed snake. I used a knife to disconnect the nozzle, take out the screws, and remove the plates and filters. When I lifted the motor’s cover the smell of dust and paper filled my nose. The fan inside was a perfect plastic flower, with curved gray petals and a small red center that made a soft clicking sound when I turned it with my finger. Clockwise, and then counterclockwise. I imagined that when the flower moved forward I was turning time, that night was falling around me. Everyone was asleep and there was no rush. I could look at all the parts of the vacuum and think about how they could be put together differently, combined with other things and made into something new.

I imagined that when the flower moved backward time reversed, to before the news about Inquiry. To before my uncle died, when he held me in his lap as he typed on his computer or pored over sheets of paper with faint blue pictures on them. I tried to imagine before that, further back than I could actually remember, to before I came to live with my aunt and uncle. Back to when my parents were alive, but the flower didn’t go that far.

I let go of the fan and began to untangle the wires coiled underneath. I wanted to understand how the suction mechanism worked, to see if it could be reversed. But I should have pulled the vacuum into my room because my cousin John found me before I had finished looking at everything. He called to my aunt, Look what June’s done! And I had to push all the parts into the closet and shut the door.

I went back to the window seat, opened my book, and pretended I’d never left. But after only a few minutes my aunt Regina came into the room. She was wearing a red wool dress with sleeves like upside-down tulips, and her hair was dark and shining.

June? Her voice was sharp.

She pulled the curtains back and saw New History of Energy in my lap. She’d told me to leave my uncle’s books alone.

There’s no point staying in here all day, she said. Go outside with your airplane—

It’s too cold.

—or finish your Monopoly game.

John cheats.

Her brown eyes were flat, unyielding.

You know he does, I said.

She pressed her hair back. Well, it’s hard to win against you, isn’t it?

I didn’t care about Monopoly. I wanted to ask her about Inquiry.

I’m going to have to pay to have that vacuum serviced, she said.

I can put it back together.

I tried, but—

It’s easy.

No, June. It’s not.

The window rattled; the spark of a rocket lit up the sky.

It would have been easy for him, I said.

She sighed. She came closer, sat down. Her shoulders bent in her red dress.

What’s wrong with Inquiry ? I tried to ask in an adult way so she would answer.

I don’t know.

They say it’s Uncle’s fault.

But we know that’s not true.

Yes.

Because he didn’t make mistakes, did he? she said.

She was very close and I could see her charcoal-colored eyelashes, could smell her bright perfume. She studied me like she was looking for something. My eyes, nose, lips. She reached to tug at a knot in my hair, but I pulled my head away.

Your hair’s tangled, she said, and stood up. Go get your brush.

When my uncle was alive I used to bring him pieces of things, screws and safety pins and button batteries, wires pulled from a broken stereo, tiny white tiles I loosened from the bathroom floor. He would look at them with a serious face and turn them over in his hands. Once I brought him the inside part of a doorknob and he asked me, What does it do? His voice was soft and precise.

Читать дальше