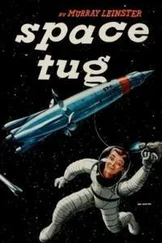

She looked at the nose of the space–ship, gleaming silver metal, rising from the trees about the landing–spot it had burned clear. A third of its length was visible.

"If it topples," said Cochrane, "we'll never be able to take off. It has to point up to lift."

Babs looked from the ship to him, and back again. Then her eyes went fearfully to the remote mountain. Rumblings came from it now. They were not loud. They were hardly more than dull growlings, at the lower limit of audible pitch. They were like faint and distant thunder. There were flashings like lightning in the cloud which now enveloped the mountain's top.

Cochrane made an indescribable small sound. He stared at the ship. As explosion–waves passed over the ground, a faint, unanimous movement of the treetops became visible. It seemed to Cochrane that the space–ship wavered as if about to fall from its upright position.

It was not designed to stand such violence as a fall would imply. Its hull would be dented or rent. It was at least possible that its fuel–store would detonate. But even if its fall were checked by still–standing trees about it, it could never take off again. The eight humans of its company could never juggle it back to a vertical position. Rocket–thrust would merely push it in the direction its nose pointed. Toppled, its rocket–thrust would merely shove it blindly over stones and trees and to destruction.

The ship swayed again. Visibly. Ground–waves made its weight have the effect of blows. Part of its foundation rested on almost–visible stone, only feet below the ground–level. But one of the landing–fins rested on humus. As the shocks passed, that fin–foot sank into the soft soil. The space–ship leaned perceptibly.

Flying creatures darted back and forth above the tree–tops. Miles away, insensate violence reigned. Clouds of dust and smoke shot miles into the air, and half a mountainside glowed white–hot, and there was the sound of long–continued thunder, and the ground shook and quivered….

There were movements nearby. A creature with yellow fur and the shape of a bear with huge ears came padding out of the forest. It swarmed up the bare stone of the hill on which Babs and Cochrane stood.

It ignored them. Halfway up the unwooded part of the hill, it stopped and made plaintive, high–pitched noises. Other creatures came. Many had come while the man and girl were too absorbed to notice. Now two more of the large animals came out into the open and climbed the hill.

Babs said shakily:

"Do you—think they'll—do you think—"

There was a nearer roaring. The space–ship leaned, and leaned…. Cochrane's lips tensed.

The space–ship's rockets bellowed and a storm of hurtling smoke flashed up around it. It lifted, staggering as its steering–jets tried frantically to swing its lower parts underneath its mass. It lurched violently, and the rockets flamed terribly. It lifted again. Its tail was higher than the trees, but it did not point straight up. It surged horribly across the top of the forest, leaving a vast flash of flaming vegetation behind it. Then it steadied, and aimed skyward and climbed….

Then it was not. Obviously the Dabney field booster had been flashed on to get the ship out to space. The ship had vanished into emptiness.

The Dabney field had flicked it some hundred and seventy–odd light–years from Earth's moon in the flicker of a heart–beat. It might have gone that far again. Whoever was in it had had no choice but to take off, and no way to take off without suicidal use of fuel in any other way.

Cochrane looked at where the ship had vanished. Seconds passed. There came the thunderclap of air closing the vacuum the ship's disappearance had left.

There were squealings behind the pair on the hilltop. Eight of the huge yellow beasts were out in the open, now. Tiny, furry biped animals waddled desperately to get out of their way. Smaller creatures scuttled here and there. A sinuous creature with fur but no apparent legs writhed its way upward. But all the creatures were frightened. They observed an absolute truce, under the overmastering greater fear of nature.

Far away, the volcano on the skyline boomed and flashed and emitted monstrous clouds of smoke. The shining, incandescent lava on its flanks glared across the glaciers.

Babs gasped suddenly. She realized the situation in which she and Cochrane had been left.

Shivering, she pressed close to him as the distant black smoke–cloud spread toward the center of the sky.

Before sunset, they reached the area of ashes where the ship had stood. Cochrane was sure that if anybody else had been left behind besides themselves, the landing–place was an inevitable rendezvous. Only three members of the ship's company had been inside when Babs and Cochrane left to stroll for the two hours astronomers on Earth had set as a waiting–period. Jones had been in the ship, and Holden, and Alicia Simms. Everybody else had been exploring. Their attitude had been exactly that of sight–seers and tourists. But they could have gotten back before the take–off.

Apparently they had. Nobody seemed to have returned to the burned–over space since the ship's departure. The blast of the rockets had erased all previous tracks, but still there was a thin layer of ash resettled over the clearing. Footprints would have been visible in it. Anybody remaining would have come here. Nobody had. Babs and Cochrane were left alone.

There were still temblors, but the sharper shocks no longer came. There was conflagration in the wood, where the lurching ship had left a long fresh streak of forest–fire. The two castaways stared at the round, empty landing–place. Overhead, the blue sky turned yellow—but where the smoke from the eruption rose, the sky early became a brownish red—and presently the yellow faded to gold. Unburned green foliage all about was singularly beautiful in that golden glow. But it was more beautiful still as the sky turned rose–pink and then carmine in turn, and then crimson from one horizon to the other save where the volcanic smoke–cloud marred the color. Then the east darkened, and became a red so deep as to be practically black, and unfamiliar bright stars began to peep through it.

Before darkness was complete, Cochrane dragged burning branches from the edge of the new fire—the heat was searing—and built a new and smaller fire in the place where the ship had been.

"This isn't for warmth," he explained briefly, "but so we'll have light if we need it. And it isn't likely that animals will be anything but afraid of it."

He went off to drag charred masses of burnable stuff from the burned–out first forest fire. He built a sort of rampart in the very center of the clearing. He brought great heaps of scorched wood. He did not know how much was needed to keep the fire going until dawn.

When he finished, Babs was silently at work trying to find out how to keep the fire going. The burning parts had to be kept together. One branch, burning alone, died out. Two red–hot brands in contact kept each other alight.

"I'm sorry we haven't anything to eat," Cochrane told her.

"I'm not hungry," she assured him. "What are we going to do now?"

"There's nothing to do until morning." Unconsciously, Cochrane looked grim. "Then there'll be plenty. Food, for one thing. We don't know, actually, whether or not there's anything really edible on this planet—for us. It could be that there are fruits or possibly stalks or leaves that would be nourishing. Only—we don't know which is which. We have to be careful. We might pick something like poison ivy!"

Babs said:

"But the ship will come back!"

"Of course," agreed Cochrane. "But it may take them some time to find us. This is a pretty big planet, you know."

Читать дальше