“Your ear is cut,” Rachael said. “What a shame.”

Rick said, “Did you really think I wouldn’t call you? As you said?”

“I told you,” Rachael said, “that without me one of the Nexus-6s would get you before you got it.”

“You were wrong.”

“But you are calling. Anyhow. Do you want me to come down there to San Francisco?”

“Tonight,” he said.

“Oh, it’s too late. I’ll come tomorrow; it’s an hour trip.”

“I have been told I have to get them tonight.” He paused and then said, “Out of the original eight, three are left.”

“You sound like you’ve had a just awful time.”

“If you don’t fly down here tonight,” he said, “I’ll go after them alone and I won’t be able to retire them. I just bought a goat,” he added. “With the bounty money from the three I did get.”

“You humans.” Rachael laughed. “Goats smell terrible.”

“Only male goats. I read it in the book of instructions that came with it.”

“You really are tired,” Rachael said. “You look dazed. Are you sure you know what you’re doing, trying for three more Nexus-6s the same day? No one has ever retired six androids in one day.”

“Franklin Powers,” Rick said. “About a year ago, in Chicago. He retired seven.”

“The obsolete McMillan Y-4 variety,” Rachael said. “This is something else.” She pondered. “Rick, I can’t do it. I haven’t even had dinner.”

“I need you,” he said. Otherwise I’m going to die, he said to himself. I know it; Mercer knew it; I think you know it, too. And I’m wasting my time appealing to you, he reflected. An android can’t be appealed to; there’s nothing in there to reach.

Rachael said, “I’m sorry, Rick, but I can’t do it tonight. It’ll have to be tomorrow.”

“Android vengeance,” Rick said.

“What?”

“Because I tripped you up on the Voigt-Kampff scale.”

“Do you think that?” Wide-eyed, she said, “ Really? ”

“Good-by,” he said, and started to hang up.

“Listen,” Rachael said rapidly. “You’re not using your head.”

“It seems that way to you because you Nexus-6 types are cleverer than humans.”

“No, I really don’t understand,” Rachael sighed. “I can tell that you don’t want to do this job tonight—maybe not at all. Are you sure you want me to make it possible for you to retire the three remaining androids? Or do you want me to persuade you not to try?”

“Come down here,” he said, “and we’ll rent a hotel room.”

“Why? “

“Something I heard today,” he said hoarsely. “About situations involving human men and android women. Come down here to San Francisco tonight and I’ll give up on the remaining andys. We’ll do something else.”

She eyed him, then abruptly said, “Okay, I’ll fly down. Where should I meet you?”

“At the St. Francis. It’s the only halfway decent hotel still in operation in the Bay Area.”

“And you won’t do anything until I get there.”

“I’ll sit in the hotel room,” he said, “and watch Buster Friendly on TV. His guest for the last three days has been Amanda Werner. I like her; I could watch her the rest of my life. She has breasts that smile.” He hung up, then, and sat for a time, his mind vacant. At last the cold of the car roused him; he switched on the ignition key and a moment later headed in the direction of downtown San Francisco. And the St. Francis Hotel.

In the sumptuous and enormous hotel room Rick Deckard sat reading the typed carbon sheets on the two androids Roy and Irmgard Baty. In these two cases telescopic snapshots had been included, fuzzy 3-D color prints which he could barely make out. The woman, he decided, looks attractive. Roy Baty, however, is something different. Something worse.

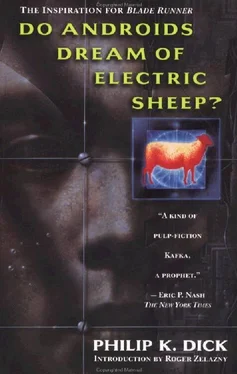

A pharmacist on Mars, he read. Or at least the android had made use of that cover. In actuality it had probably been a manual laborer, a field hand, with aspirations for something better. Do androids dream? Rick asked himself. Evidently; that’s why they occasionally kill their employers and flee here. A better life, without servitude. Like Luba Luft; singing Don Giovanni and Le Nozze instead of toiling across the face of a barren rock-strewn field. On a fundamentally uninhabitable colony world.

Roy Baty (the poop sheet informed him) has an aggressive, assertive air of ersatz authority. Given to mystical preoccupations, this android proposed the group escape attempt, underwriting it ideologically with a pretentious fiction as to the sacredness of so-called android “life.” In addition, this android stole, and experimented with, various mind-fusing drugs, claiming when caught that it hoped to promote in androids a group experience similar to that of Mercerism, which it pointed out remains unavailable to androids.

The account had a pathetic quality. A rough, cold android, hoping to undergo an experience from which, due to a deliberately built-in defect, it remained excluded. But he could not work up much concern for Roy Baty; he caught, from Dave’s jottings, a repellent quality hanging about this particular android. Baty had tried to force the fusion experience into existence for itself—and then, when that fell through, it had engineered the killing of a variety of human beings … followed by the flight to Earth. And now, especially as of today, the chipping away of the original eight androids until only the three remained. And they, the outstanding members of the illegal group, were also doomed, since if he failed to get them someone else would. Time and tide, he thought. The cycle of life. Ending in this, the last twilight. Before the silence of death. He perceived in this a micro-universe, complete.

The door of the hotel room banged open. “What a flight,” Rachael Rosen said breathlessly, entering in a long fish-scale coat with matching bra and shorts; she carried, besides her big, ornate, mail-pouch purse, a paper bag. “This is a nice room.” She examined her wristwatch. “Less than an hour—I made good time. Here.” She held out the paper bag. “I bought a bottle. Bourbon.”

Rick said, “The worst of the eight is still alive. The one who organized them.” He held the poop sheet on Roy Baty toward her; Rachael set down the paper bag and accepted the carbon sheet.

“You’ve located this one?” she asked, after reading.

“I have a conapt number. Out in the suburbs where possibly a couple of deteriorated specials, antheads and chickenheads, hang out and go through their versions of living.”

Rachael held out her hand. “Let’s see about the others.”

“Both females.” He passed her the sheets, one dealing with Irmgard Baty, the other an android calling itself Pris Stratton.

Glancing at the final sheet Rachael said, “Oh—” She tossed the sheets down, moved over to the window of the room to look out at downtown San Francisco. “I think you’re going to get thrown by the last one. Maybe not; maybe you don’t care.” She had turned pale and her voice shook. All at once she had become exceptionally unsteady.

“Exactly what are you muttering about?” He retrieved the sheets, studied them, wondering which part had upset Rachael.

“Let’s open the bourbon.” Rachael carried the paper bag into the bathroom, got two glasses, returned; she still seemed distracted and uncertain—and preoccupied. He sensed the rapid flight of her hidden thoughts: the transitions showed on her frowning, tense face. “Can you get this open?” she asked. “It’s worth a fortune, you realize. It’s not synthetic; it’s from before the war, made from genuine mash.”

Taking the bottle he opened it, poured bourbon in the two tumblers. “Tell me what’s the matter,” he said.

Читать дальше