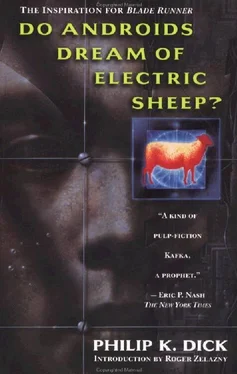

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

by Philip K. Dick

To Maren Augusta Bergrud

August 10, 1923—June 14, 1967

And still i dream he treads the lawn,

Walking ghostly in the dew,

Pierced by my glad singing through.

Yeats

Auckland

A turtle which explorer captain Cook gave to the king of Tonga in 1777 died yesterday.

It was nearly 200 years old. The animal, called Tu’imalila, died at the Royal Palace Ground in the Tongan capital of Nuku, Alofa.

The people of Tonga regarded the animal as a chief and special keepers were appointed to look after it. It was blinded in a bush fire a few years ago.

Tonga radio said Tu’imalila’s carcass would be sent to the Auckland museum in New Zealand.

Reuters, 1966

A merry little surge of electricity piped by automatic alarm from the mood organ beside his bed awakened Rick Deckard. Surprised—it always surprised him to find himself awake without prior notice—he rose from the bed, stood up in his multicolored pajamas, and stretched. Now, in her bed, his wife Iran opened her gray, unmerry eyes, blinked, then groaned and shut her eyes again.

“You set your Penfield too weak,” he said to her. “I’ll reset it and you’ll be awake and—”

“Keep your hand off my settings.” Her voice held bitter sharpness. “I don’t want to be awake.”

He seated himself beside her, bent over her, and explained softly. “If you set the surge up high enough, you’ll be glad you’re awake; that’s the whole point. At setting C it overcomes the threshold barring consciousness, as it does for me.” Friendlily, because he felt well-disposed toward the world — his setting had been at D –he patted her bare, pale shoulder.

“Get your crude cop’s hand away,” Iran said.

“I’m not a cop—” He felt irritable, now, although he hadn’t dialed for it.

“You’re worse,” his wife said, her eyes still shut. “You’re a murderer hired by the cops.

“I’ve never killed a human being in my life.” His irritability had risen, now; had become outright hostility.

Iran said, “Just those poor andys.”

“I notice you’ve never had any hesitation as to spending the bounty money I bring home on whatever momentarily attracts your attention.” He rose, strode to the console of his mood organ. “Instead of saving,” he said, “so we could buy a real sheep, to replace that fake electric one upstairs. A mere electric animal, and me earning all that I’ve worked my way up to through the years.” At his console he hesitated between dialing for a thalamic suppressant (which would abolish his mood of rage) or a thalamic stimulant (which would make him irked enough to win the argument).

“If you dial,” Iran said, eyes open and watching, “for greater venom, then I’ll dial the same. I’ll dial the maximum and you’ll see a fight that makes every argument we’ve had up to now seem like nothing. Dial and see; just try me.” She rose swiftly, loped to the console of her own mood organ, stood glaring at him, waiting.

He sighed, defeated by her threat. “I’ll dial what’s on my schedule for today.” Examining the schedule for January 3, 1992, he saw that a businesslike professional attitude was called for. “If I dial by schedule,” he said warily, “will you agree to also?” He waited, canny enough not to commit himself until his wife had agreed to follow suit.

“My schedule for today lists a six-hour self-accusatory depression,” Iran said.

“What? Why did you schedule that?” It defeated the whole purpose of the mood organ. “I didn’t even know you could set it for that,” he said gloomily.

“I was sitting here one afternoon,” Iran said, “and naturally I had turned on Buster Friendly and His Friendly Friends and he was talking about a big news item he’s about to break and then that awful commercial came on, the one I hate; you know, for Mountibank Lead Codpieces. And so for a minute I shut off the sound. And I heard the building, this building; I heard the—” She gestured.

“Empty apartments,” Rick said. Sometimes he heard them at night when he was supposed to be asleep. And yet, for this day and age a one-half occupied conapt building rated high in the scheme of population density; out in what had been before the war the suburbs one could find buildings entirely empty … or so he had heard. He had let the information remain secondhand; like most people he did not care to experience it directly.

“At that moment,” Iran said, “when I had the TV sound off, I was in a 382 mood; I had just dialed it. So although I heard the emptiness intellectually, I didn’t feel it. My first reaction consisted of being grateful that we could afford a Penfield mood organ. But then I read how unhealthy it was, sensing the absence of life, not just in this building but everywhere, and not reacting—do you see? I guess you don’t. But that used to be considered a sign of mental illness; they called it ‘absence of appropriate affect.’ So I left the TV sound off and I sat down at my mood organ and I experimented. And I finally found a setting for despair.” Her dark, pert face showed satisfaction, as if she had achieved something of worth. “So I put it on my schedule for twice a month; I think that’s a reasonable amount of time to feel hopeless about everything, about staying here on Earth after everybody who’s small has emigrated, don’t you think?”

“But a mood like that,” Rick said, “you’re apt to stay in it, not dial your way out. Despair like that, about total reality, is self-perpetuating.”

“I program an automatic resetting for three hours later,” his wife said sleekly. “A 481. Awareness of the manifold possibilities open to me in the future; new hope that—”

“I know 481,” he interrupted. He had dialed out the combination many times; he relied on it greatly. “Listen,” he said, seating himself on his bed and taking hold of her hands to draw her down beside him, “even with an automatic cutoff it’s dangerous to undergo a depression, any kind. Forget what you’ve scheduled and I’ll forget what I’ve scheduled; we’ll dial a 104 together and both experience it, and then you stay in it while I reset mine for my usual businesslike attitude. That way I’ll want to hop up to the roof and check out the sheep and then head for the office; meanwhile I’ll know you’re not sitting here brooding with no TV.” He released her slim, long fingers, passed through the spacious apartment to the living room, which smelled faintly of last night’s cigarettes. There he bent to turn on the TV.

From the bedroom Iran’s voice came. “I can’t stand TV before breakfast.”

“Dial 888,” Rick said as the set warmed. “The desire to watch TV, no matter what’s on it.”

“I don’t feel like dialing anything at all now,” Iran said.

“Then dial 3,” he said.

“I can’t dial a setting that stimulates my cerebral cortex into wanting to dial! If I don’t want to dial, I don’t want to dial that most of all, because then I will want to dial, and wanting to dial is right now the most alien drive I can imagine; I just want to sit here on the bed and stare at the floor.” Her voice had become sharp with overtones of bleakness as her soul congealed and she ceased to move, as the instinctive, omnipresent film of great weight, of an almost absolute inertia, settled over her.

He turned up the TV sound, and the voice of Buster Friendly boomed out and filled the room. “—ho ho, folks. Time now for a brief note on today’s weather. The Mongoose satellite reports that fallout will be especially pronounced toward noon and will then taper off, so all you folks who’ll be venturing out—”

Читать дальше