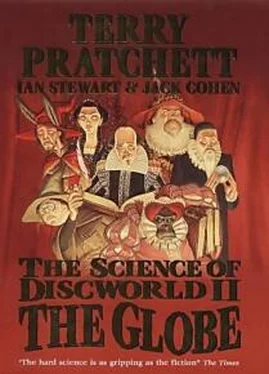

Terry Pratchett - The Globe

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Terry Pratchett - The Globe» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Globe

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Globe: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Globe»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Globe — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Globe», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

mostly works like the driving test, but with the added complication that just occasionally it really is more like a tennis match.

From this point of view, evolution is a complex system, with organisms as entities. Which organisms survive to reproduce, and which do not, are system-level properties. They depend as much on context (American driving test versus British) as on the internal features of the individuals. The survival of a species is an emergent feature of the whole system, and no simple short-cut computation can predict it. In particular, computations based on the frequencies of genes in the gene-pool can't predict it, and the alleged explanation of altruism by gene- frequencies is unconvincing.

Why, then, does altruism arise? An intriguing answer was given by Randolph Nesse in the magazine Science and Spirit in 1999. In a word, his answer is 'overcommitment'. And it is a refreshing and much-needed alternative to bean-counting.

We have said more than once that humans are time-binders. We run our lives not just on what is happening now, but on what we think will happen in the future. This makes it possible for us to commit ourselves to a future action. 'If you fall sick, I will look after you.' 'If an enemy attacks you, I will come to your aid.' Commitment strategies change the face of 'competition'

completely. An example is the strategy of 'mutual assured destruction' as a deterrent for nuclear war: 'If you attack me with nuclear weapons, I will use mine to destroy your country completely.'

Even if one country has many more nuclear weapons, which on a bean-counting basis means that it will 'win', the commitment strategy means that it can't.

If two people, tribes or nations make a pact, and agree to commit support to each other, then they are both strengthened, and their survival prospects increase. (Provided it's a sensible pact. We leave you to invent scenarios where what we've just said is wrong.) Ah, yes, that's all very well, but can you trust the other to keep to the agreement? We have evolved some quite effective methods for deciding whether or not to trust someone. At the simplest level, we watch what they do and compare it to what they say. We can also try to find out how they have behaved in similar circumstances before. As long as we can get such decisions right most of the time, they offer a substantial survival advantage. They improve how well we do, against the background of everything else. Comparison with others is irrelevant.

From a bean-counter's point of view, the 'correct' strategy in such circumstances is to count how many beans you gain by committing yourself, compare that to how many you gain by cheating, and see which pile of beans is biggest. From Nesse's point of view, that approach doesn't amount to a hill of beans. The whole calculation can be sidestepped, at a stroke, by the strategy of overcommitment. 'Stuff the beans: I guarantee that I will commit myself to you, no matter what.

And you can trust me, because I will prove to you, and keep proving it every day that we live, that I am committed at that level.' Overcommitment beats the bean-counters hands down. While they're trying to compare 142 beans with 143, overcommitment has wiped the floor with them.

Nesse suggests that such strategies have had a decisive effect in shaping our extelligence (though he doesn't use that word): Commitment strategies give rise to complexities that may be a selective force that has shaped human intelligence. This is why human psychology and relationships are so hard to fathom.

Perhaps a better understanding of the deep roots of commitment will illuminate the relationships between reason and emotion, and biology and belief.

Or, to put it another way: perhaps that's what gave us an edge over the Neanderthals. Though it would be difficult to find a scientific test for such a suggestion.

When humans overcommit in this manner, we call it 'love'. There is far more to love than the simple scenario just outlined, of course, but one feature is common to both: love counts not the cost. It doesn't care about who gets the most beans.55 And by refusing to play the bean-counters'

game, it wins outright. Which is a very religious, spiritual and uplifting message. And sound evolutionary sense. What more could we ask?

Quite a bit, actually, because now it all starts to get nasty. The reasons, however, are admirable.

Every culture needs its own Make-a-Human kit, to build into the next generation the kind of mind that will keep the culture going -and, recursively, ensure that the next generation does the same for the one that comes after that. Rituals fit very readily into such a kit, because it is easy to distinguish Us from Them by the rituals that We follow but They don't.56 It is also an excellent test of a child's willingness to obey cultural norms by insisting that they carry out some perfectly ordinary task in an unnecessarily prescribed and elaborate manner.

Now, however, the priesthood has got its ideological toe in the cultural doorway. Rituals need someone to organise them, and to elaborate them. Every bureaucracy builds itself an empire by creating unnecessary tasks and then finding people to carry them out. A crucial task here is to ensure that members of the tribe or village or nation really do obey the norms and carry out the rituals. There has to be some sanction to make sure that they do, even if they're free-thinking types who'd rather not. Because everything is founded on an ontically dumped concept, reference to reality has to be replaced by belief. The less testable a human belief is, the more strongly we tend to hold on to it. Deep down we recognise that although not being testable means that disbelievers can't prove we're wrong, it also means that we can't prove we're right. Since we know that we are, that sets up a tremendous tension.

Now the atrocities begin. Religion slides over the edge of sanity, and the result is horrors like the Spanish Inquisition. Think about it for a moment. The priesthood of a religion whose central tenet was universal love and brotherhood systematically inflicted appalling tortures, sick and disgusting things, on innocent people who merely happened to disagree about minor items of belief. This is a massive contradiction and it demands explanation. Were the Inquisitors evil people who knowingly did evil things?

Small Gods, one of the most profound and philosophical of the Discworld novels, examines the role of belief in religions, and Discworld undergoes its own version of the Spanish Inquisition.

One twist is that on Discworld, there is no lack of gods; however, few of them have any great significance: There are billions of gods in the world. They swarm as thick as herring roe. Most of them are too small to see and never get worshipped, at least by anything bigger than bacteria, who never say their prayers and don't demand much in the way of miracles.

They are the small gods, the spirits of places where two ant trails cross, the gods of microclimates down between the grass roots. And most of them stay that way.

Because what they lack is belief.

Small Gods is the story of one rather larger god, the Great God Om, who manifests himself to a novice monk called Brutha, in the Citadel at the heart of the city of Kom in the lands between the deserts of Klatch and the jungles of Howondaland.

Brutha's attitude to religion is a very personal one. He runs his own life by it. In contrast, Deacon Vorbis believes that the role of religion is to run everybody else's life. Vorbis is head of the Quisition, whose role is 'to do all those things that needed to be done and which other people would rather not do'. Nobody ever interrupts Vorbis to ask what he is thinking about, because they are scared stiff that the answer will be 'You'.

The Great God's manifestation takes the form of a small tortoise. Brutha finds this hard to believe: I've seen the Great God Om ... and he isn't tortoise-shaped. He comes as an eagle, or a lion, or a mighty bull. There's a statue in the Great Temple. It's seven cubits high. It's got bronze on it and everything. It's trampling infidels. You can't trample infidels when you're a tortoise.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Globe»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Globe» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Globe» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.