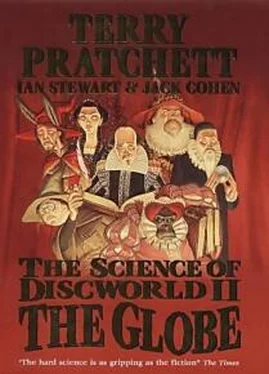

Terry Pratchett - The Globe

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Terry Pratchett - The Globe» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Globe

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Globe: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Globe»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Globe — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Globe», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

'goose summer'. What's that got to do with fine threads that float on the breeze? Well, in a summer when geese abound, a good summer, you find a lot of these fine spider-silk threads hanging in the air ...

Subconsciously, though, we are all too aware of the dark associations several layers down in the ontic-dumping hierarchy. So words, which ought to be abstract labels, are smeared all over with their own (often irrelevant) stories.

Abraham, then, was overawed by 'that which is', and he ontically dumped it into a word, Jehovah. Which quickly became a thing, indeed, a person. That's another of our habits, personifying things. So Abraham made the tiny step from 'there is something outside us that is greater than ourselves' to 'there is someone outside us who is greater than ourselves'. He had looked on the burgeoning extelligence of his own culture, and before his eyes it turned into God.

And that made so much sense. It explained so much else. Instead of the world being like it was for reasons he couldn't understand -even though that greater something clearly understood it perfectly well -he now saw that the world was like that because God had made it that way. The rain fell not because some tawdry idol rain-god made it fall; Abraham was too smart to believe that. It fell because that awesome God whose presence could be seen everywhere made it fall.

And he, Abraham, couldn't hope to understand the Mind of God, so of course he couldn't predict when it would rain.

We have used Abraham here as a placeholder. Choose your religion, choose your founder, adapt the story to fit. We're not saying that we know that the birth of Judaism happened the way we've just explained. That was just a story, probably no more true than Winnie-the-Pooh and the honey.

But just as Pooh in the rabbit-hole teaches us about greed, so Abraham's ontic dumping points to a plausible route whereby sane, sensitive people can be led from their own private spiritual feelings to reify a natural process into an unfathomable Being.

This reification has had many positive consequences. People take notice of the wishes of unfathomable, all-powerful Beings. Religious teachings often lay down guidelines (laws, commandments) for acceptable behaviour towards other people. To be sure, there are many disagreements between the different religions, or between sects within a given religion, about points of fine detail. And there are some quite substantial areas of disagreement, such as the recommended treatment of women, or to what extent basic rights should be extended to the infidel. On the whole, however, there is a strong consensus in such teachings, for example an almost universal condemnation of theft and murder. Virtually all religions reinforce a very similar consensus of what constitutes 'good' behaviour, perhaps because it is this consensus that has survived the test of time. In terms of the barbarian/tribal distinction, it is a tribal consensus, reinforced by tribal methods such as ritual, but none the worse for that.

Many people find inspiration in their religion, and it helps instil a sense of belonging. It enhances their feeling of what an awesome place the universe is. It helps them cope with disasters. With exceptions, mainly related to specific circumstances such as war, most religions preach that love is good and hatred is bad. And throughout history, ordinary people have made huge sacrifices, often of their own lives, on that basis.

This kind of behaviour, generally referred to as altruism, has caused evolutionary biologists a great deal of head-scratching. First, we'll summarise how they have thought about the problem and what kinds of conclusion they have reached. Then we'll consider an alternative approach, originally motivated by religious considerations, which looks to us to be far more promising.

At first sight, altruism is not a problem. If two organisms cooperate, by which in this context we here mean that each is willing to risk its life to help the other,53 then both stand to gain. Natural selection favours such an advantage, and reinforces it. What more explanation is needed?

Quite a lot, unfortunately. A standard reflex in evolutionary biology is to ask whether such a situation is stable -whether it will persist if some organisms adopt other strategies. What happens, for example, if most organisms cooperate, but a few decide to cheat? If the cheats prosper, then it is better to become a cheat than to cooperate, and the strategy of cooperation is unstable and will die out. Using the methods of mid-twentieth-century genetics, the approach pioneered by Ronald Aylmer Fisher, you can do the sums and work out the circumstances in which altruism is an evolutionarily stable strategy. The answer is that it all depends upon whom you cooperate with, whose life you risk your own to save. The closer kin they are to you, the more genes they share with you, so the more worthwhile it is for you to risk your own safety.

This analysis leads to conclusions like 'It is worth jumping into a lake to save your sister, but not to save your aunt.' And certainly not to save a stranger.

That's the genetic orthodoxy, and like most orthodoxies, it is believed by the orthodox. On the other hand, though: if someone has fallen into a lake, people do not ask 'Excuse me, sir, but how closely related are you to me? Are you, by any chance, a close relative?' before diving in to rescue them. If they are the sort of people who dive in, they do so whoever has fallen into the lake. If not, they don't. Mostly. A clear exception arises when a child falls in; even if they can't swim its parent is then very likely indeed to plunge in to the rescue, but probably would not do so for someone else's child, and even less so for an adult. So the genetic orthodoxy does have a certain amount going for it.

Not much, though. Fisher's mathematics is rather old-fashioned, and it rests on a big -and very shaky -modelling simplification.54 It represents a species by its gene-pool, where all that matters is the proportion of organisms that possess a given gene. Instead of comparing different strategies that might be adopted by an organism, it works out what strategy is best 'on average'.

And inasmuch as individual organisms are represented within its framework at all, which they are only as contributors to the gene-pool, it views competition between organisms as a direct 'me versus thee' choice. A bird that eats seeds is up against a bird that eats worms in a head-to-head struggle for survival, like two tennis-players ... and may the best bird win.

This is a bean-counting analysis performed with a bean-counting mentality. The bird with the most beans (energy from seeds or worms, say) survives; the other does not.

From a complex system viewpoint, evolution isn't like that at all. Organisms may sometimes compete directly -two birds tugging at the same worm, for instance. Or two baby birds in the nest, where direct competition can be fierce and fatal. But mostly the competition is indirect -so indirect that 'compete' just isn't the right word. Each individual bird either survives, or not, against the background of everything else, including the other birds. Birds A and B do not go head-to-head. They compete against each other only in the sense that we choose to compare how A does with how B does, and declare one of them to be more successful.

It's like two teenagers taking driving tests. Maybe one of them is in the UK and the other is in the USA. If one passes and the other fails, then we can declare the one who has passed to be the

'winner'. But the two teenagers don't even know they are competing, for the very good reason that they're not. The success or failure of one has no effect on the success or failure of the other.

Nevertheless, one gets to drive a car, and the other doesn't.

The driving-test system works that way, and it doesn't matter that the American test is easier to pass than the British one (as we can attest from personal experience). Evolutionary 'competition'

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Globe»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Globe» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Globe» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.