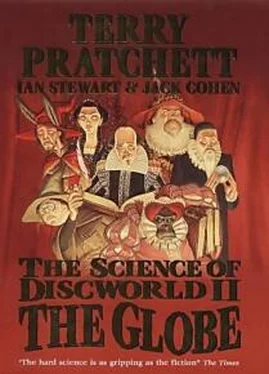

Terry Pratchett - The Globe

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Terry Pratchett - The Globe» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Globe

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Globe: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Globe»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Globe — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Globe», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

111111111111111 then there is no great surprise if the next bit turns out to be 1; but if the signal reads 111001101101011 (which we obtained by tossing a coin 15 times) then there is no obvious guess for the next bit.

Both measures of information are useful in the design of electronic technology. Shannon information governs the time it takes to transmit a signal somewhere else; Chaitin information tells you whether there's a clever way to compress the signal first, and transmit something smaller. At least, it would do if you could calculate it, but one of the features of Chaitin's theory is that it is impossible to calculate the amount of algorithmic information in a message -and he can prove it. The wizards would approve of this twist.

'Information' is therefore a useful concept, but it is curious that 'To be or not to be' contains the same Shannon information as, and less Chaitin information than, 'xyQGRlfryu&d°/oskOwc'. The reason for this disparity is that information is not the same thing as meaning. That's fascinating.

What really matters to people is the meaning of a message, not its bit-count, but mathematicians have been unable to quantify meaning. So far.

And that brings us back to stories, which are messages that convey meaning. The moral is that we should not confuse a story with 'information'. The elves gave humanity stories, but they didn't give them any information. In fact, the stories people came up with included things like werewolves, which don't even exist on Roundworld. No information there -at least, apart from what it might tell you about the human imagination.

Most people, scientists in particular, are happiest with a concept when they can put a number to it. Anything else, they feel, is too vague to be useful. 'Information' is a number, so that comfortable feeling of precision slips in without anyone noticing that it might be spurious. Two sciences that have gone a long way down this slippery path are biology and physics.

The discovery of the linear molecular structure of DNA has given evolutionary biology a seductive metaphor for the complexity of organisms and how they evolve, namely: the genome of an organism represents the information that is required to construct it. The origin of this metaphor is Francis Crick and James Watson's epic discovery that an organism's DNA consists of 'code words' in the four molecular 'letters' A C T G, which, you'll recall, are the initials of the four possible 'bases'. This description led to the inevitable metaphor that the genome contains information about the corresponding organism. Indeed, the genome is widely described as

'containing the information needed to produce' an organism.

The easy target here is the word 'the'. There are innumerable reasons why a developing organism's DNA does not determine the organism. These non-genomic influences on development are collectively known as 'epigenetics', and they range from subtle chemical tagging of DNA to the investment of parental care. The hard target is 'information'. Certainly, the genome includes information in some sense: currently an enormous international effort is being devoted to listing that information for the human genome, and also for other organisms such as rice, yeast, and the nematode worm Caenorhabditis elegans. But notice how easily we slip into cavalier attitudes, for here the word 'information' refers to the human mind as receiver, not to the developing organism. The Human Genome Project informs us, not organisms.

This flawed metaphor leads to the equally flawed conclusion that the genome explains the complexity of an organism in terms of the amount of information in its DNA code. Humans are complicated because they have a long genome that carries a lot of information; nematodes are less complicated because their genome is shorter. However, this seductive idea can't be true. For example, the Shannon information content of the human genome is smaller by several orders of magnitude than the quantity of information needed to describe the wiring of the neurons in the human brain. How can we be more complex than the information that describes us? And some amoebas have much longer genomes than ours, which takes us down several pegs as well as casting even more doubt on DNA as information.

Underlying the widespread belief that DNA complexity explains organism complexity (even though it clearly doesn't) are two assumptions, two scientific stories that we tell ourselves. The first story is DNA as Blueprint, in which the genome is represented not just as an important source of control and guidance over biological development, but as the information needed to determine an organism. The second is DNA as Message, the 'Book of Life' metaphor.

Both stories oversimplify a beautifully complex interactive system. DNA as Blueprint says that the genome is a molecular 'map' of an organism. DNA as Message says that an organism can pass that map to the next generation by 'sending' the appropriate information.

Both of these are wrong, although they're quite good science fiction -or, at least, interestingly bad science fiction with good special effects.

If there is a 'receiver' for the DNA 'message' it is not the next generation of the organism, which does not even exist at the time the 'message' is being 'sent', but the ribosome, which is the molecular machine that turns DNA sequences (in a protein-coding gene) into protein. The ribosome is an essential part of the coding system; it functions as an 'adapter', changing the sequence information along the DNA into an amino acid sequence in proteins. Every cell contains many ribosomes: we say 'the' because they are all identical. The metaphor of DNA as information has become almost universal, yet virtually nobody has suggested that the ribosome must be a vast repository of information. The structure of the ribosome is now known in high detail, and there is no sign of obvious 'information-bearing' structure like that in DNA. The ribosome seems to be a fixed machine. So where has the information gone? Nowhere. That's the wrong question.

The root of these misunderstandings lies in a lack of attention to context. Science is very strong on content, but it has a habit of ignoring 'external' constraints on the systems being studied.

Context is an important but neglected feature of information. It is so easy to focus on the combinatorial clarity of the message and to ignore the messy, complicated processes carried out by the receiver when it decodes the message. Context is crucial to the interpretation of messages: to their meaning. In his book The User Illusion Tor Norretranders introduced the term exformation to capture the role of the context, and Douglas Hofstadter made the same general point in Godel, Escher, Bach. Observe how, in the next chapter, the otherwise incomprehensible message 'THEOSTRY' becomes obvious when context is taken into account.

Instead of thinking about a DNA 'blueprint' encoding an organism, it's easier to think of a CD

encoding music. Biological development is like a CD that contains instructions for building a new CD-player. You can't 'read' those instructions without already having one. If meaning does not depend upon context, then the code on the CD should have an invariant meaning, one that is independent of the player. Does it, though?

Compare two extremes: a 'standard' player that maps the digital code on the CD to music in the manner intended by the design engineers, and a jukebox. With a normal jukebox, the only message that you send is some money and a button-push; yet in the context of the jukebox these are interpreted as a specific several minutes' worth of music. In principle, any numerical code can 'mean' any piece of music you wish; it just depends on how the jukebox is set up, that is, on the exformation associated with the jukebox's design. Now consider a jukebox that reacts to a CD not by playing the tune that's encoded on it, as a series of bits, but by interpreting that code as a number, and then playing some other CD to which that number has been assigned. For instance, suppose that a recording of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony starts, in digital form, with

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Globe»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Globe» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Globe» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.