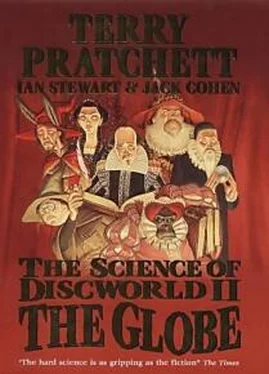

Terry Pratchett - The Globe

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Terry Pratchett - The Globe» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Globe

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Globe: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Globe»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Globe — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Globe», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

One set of ideas. If you expect your one God to be consistent, then it's worth asking how those causalities relate to each other: for example, 'black clouds and rain will be associated with thunderstorms when ..." whatever. The monotheist can predict the weather, even if rather badly.

But the polytheist needs a theopsychologist and a precise account of what the gods are up to at the moment. She needs to know whether a tiff between two gods will result in a thunderstorm.

So scientific causality is compatible with God-causality, but not with gods-causality.

Monotheists, moreover, have a built-in intolerance. The position that there is only one truth, only one avenue to the one God, sets each monotheistic religion in opposition to all others. There is no room for manoeuvre, no way to tolerate the manifest errors of people who believe in some other god. So monotheism laid the foundation for the Inquisition, and for intemperate Christianity through the ages from the crusades through to African and Polynesian missionaries.

'I have the story, and it is the only one' is characteristic of many cults, all of them intolerant.

Faiths, of course, do get along. But they get along because of the hammering they have taken at the hands of science, material development and better education. They get along because of wise people within them who recognise the commonality of humanity. Where there are too few wise people, you get Northern Ireland. If you are lucky.

If the future is not fixed, but malleable, and we can predict the effects of our present behaviour, however badly, then predicting the future can be self-defeating. And that can even be the reason for predicting it.

Most of the Biblical prophets seem, like many science-fiction authors today, to be warning against what might happen if we go on as we are doing. So they succeed when their prophecy is not correct, because people heed it and change their actions. We can understand that; even though the prophecy didn't come true, we can all see that it might have done: it has given us a better idea of the phase space that the future of our culture lives in.

What about the gypsy who prophesies that a tall dark man will come into your life, thus making you receptive to all those future tall dark men? (if tall dark men interest you, of course; it's up to you.) This could be a self-fulfilling prophecy, the opposite of the stories told by Biblical prophets. It's a story that the recipient is sympathetic to, wants to happen.

There are said to be only seven basic story plots, so perhaps our minds are much less varied than we think, so that the newspaper astrologer and the fortune-teller are navigating a much smaller phase space of human experience than we thought. This would account for so many people feeling that the predictions show deep insight.

But when astronomers predict the future, and get it right, people are, paradoxically, much less impressed. When they predict eclipses correctly, every time, this seems less meaningful than the astrologers nearly getting many people right, sometimes. Remember Y2K, the prophecy that planes would fall out of the sky soon after the year 2000 dawned and your toaster wouldn't work? That prophecy cost the world several billion dollars in work to avert the problem -and it didn't happen. A waste of time, then? Not at all. It didn't happen because people took precautions. If they hadn't done, the cost would have been much higher. It was a Biblical prophecy: 'If this goes on ...' And, lo, the multitude heeded.

This recursive dependence of prophecy upon people's responses to it, unlike most of the other kinds of thing that we say, relates back to our facility with our own made-up little futures, the stories that we tell ourselves. They confirm us in our identities. It is no wonder that when someone -an astrologer or Nostradamus, say -pokes his finger into this mental place where we live, and inserts some of his own stories, we want to believe him. His stories are more exciting than ours. We wouldn't have thought, going down the stairs to get a train to work, 'I wonder if I'm going to meet a tall dark guy today?' But once it's been put into our minds, we smile at all the dark men, even some quite short ones. And so our lives are changed (perhaps in quite major ways, if you are a man doing the smiling) as are the stories that we ourselves proposed for our futures.

This way that we react, fairly predictably, to what the world throws at us, casts doubt on our otherwise unshakeable belief that we get to choose what we do. Do we truly possess free will? Or are we like the amoeba, drifting this way and that, propelled by the dynamic of a phase space that cannot be perceived from outside?

In Figments of Reality we included a chapter with the title 'We wanted to have a chapter on free will but we decided not to, so here it is'. There we examined such issues as whether, in a world without genuine free will, it would be fair to blame a person for their actions. We conclude that in a world without genuine free will, there might not be any choice: they would get blamed anyway because the possibility of them not being blamed did not exist.

We won't go over that ground in detail, but we do want to summarise the main thrust of the argument. We start by observing that there is no effective scientific test for free will. You can't run the universe again, with everything exactly as it was, and see if a different choice can be made second time round. Moreover, there seems to be no room in the laws of physics for genuine free will. Quantum indeterminacy, seized on so readily by many philosophers and scientists as a catch-all explanation of 'consciousness', is the wrong kind of thing altogether: random unpredictability is not the same as choosing between clear alternatives.

There are many ways in which the known laws of physics could offer an illusion of free will, for example by exploiting chaos or emergence, but there is no way to set up a system that could make different choices even though every particle in the universe, including those making up the system, is in the same state on both occasions.

Add to this one rather interesting aspect of human social behaviour: although we feel as if we have free will, we don't act as if we believe that anybody else has. When somebody does something uncharacteristic, 'not like them', we don't say 'Oh, Fred is exercising his free will. He's been a lot happier since he smiled at the tall, dark stranger.' We say 'What the devil has got into Fred?' Only when we find a reason for his actions, an explanation not involving the exercise of free will (like drunkenness, or 'doing it for a bet') do we feel satisfied.

All of this suggests that our minds do not actually make choices: they make judgements. Those judgements reveal not what we have chosen, but what kind of mind we possess. 'Well, I never would have guessed,' we say, and feel we've learned something that we can use in future dealings with that person.

So what about that strong feeling that we get, of making a choice? That's not what we're doing, it's what it feels like to us when we're doing it, just as that vivid grey quale of the visual system is not actually out there on the elephant, but an added decoration that exists in our heads.

'Choosing' is what our minds feel like from inside when they're judging between alternatives.

Free will is not a real attribute of human beings at all: it is merely the quale of judgement.

FREEDOM OF INFORMATION

People believed that elves could look like anything they wanted to, but this was, strictly speaking, wrong. Elves looked the same all the time (rather dull and grey, with large eyes, rather similar to bushbabies without the charm) but they could, without effort, cause others to see them differently.

Currently the Queen looked like a fashionable lady of the time, in black lace, sparkling here and there with diamonds. Only with a hand over one eye and extreme concentration could even a trained wizard dimly see the true nature of the elf, and even then his eye would water alarmingly.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Globe»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Globe» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Globe» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.