“How is he?”

“Who knows? They’ve got wards and wards of people and none of them can have visitors. It’s spooky, Larry. And there are lot of soldiers around.”

“On leave?”

“Soldiers on leave don’t carry guns or ride around in convoy trucks. A lot of people are really scared. You’re well off out where you are.”

“Hasn’t been anything on the news.”

“Out here there’s been a few things in the papers about getting flu boosters, that’s all. But some people are saying the army got careless with one of those little plague jars. Isn’t that creepy ?”

“It’s just scare talk.”

“There’s nothing like it where you are?”

“No,” he said, and then thought of his mother’s cold. And hadn’t there been a lot of sneezing and hacking going on in the subway? He remembered thinking it sounded like a TB ward. But there were plenty of sneezes and runny noses to go around in any city. Cold germs are gregarious, he thought. They like to share the wealth.

“Janey herself isn’t in,” Arlene was saying. “She’s got a fever and swollen glands, she said. I thought that old whore was too tough to get sick.”

“Three minutes are up, signal when through,” the operator broke in.

Larry said: “Well, I’ll be coming back in a week or so, Arlene. We’ll get together.”

“Fine by me. I always wanted to go out with a famous recording star.”

“Arlene? You don’t by any chance know a guy named Dewey the Deck, do you?”

“Oh!” she said in a very startled way. “Oh wow! Larry!”

“What?”

“Thank God you didn’t hang up! I did see Wayne, just about two days before he went into the hospital. I forgot all about it! Oh, gee!”

“Well, what is it?”

“It’s an envelope. He said it was for you, but he asked me to keep it in my cash drawer for a week or so, or give it to you if I saw you. He said something like ‘He’s goddam lucky Dewey the Deck isn’t collecting it instead of him.’”

“What’s in it?” He switched the phone from one hand to the other.

“Just a minute. I’ll see.” There was a moment of silence, then ripping paper. Arlene said, “It’s a savings account book. First Commercial Bank of California. There’s a balance of… wow! Just over thirteen thousand dollars. If you ask me to go somewhere dutch, I’ll brain you.”

“You won’t have to,” he said, grinning. “Thanks, Arlene. Hang on to that for me, now.”

“No, I’ll throw it down a storm-drain. Asshole.”

“It’s so good to be loved.”

She sighed. “You’re too much, Larry. I’ll put it in an envelope with both our names on it. Then you can’t duck me when you come in.”

“I wouldn’t do that, sugar.”

They hung up and then the operator was there, demanding three more dollars for Ma Bell. Larry, still feeling the wide and foolish grin on his face, plugged it willingly into the slot.

He looked at the change still scattered on the phone booth’s shelf, picked out a quarter, and dropped it into the slot. A moment later his mother’s phone was ringing. Your first impulse is to share good news, your second is to club someone with it. He thought—no, he believed—that this was entirely the former. He wanted to relieve both of them with the news that he was solvent again.

The smile faded off his lips little by little. The phone was only ringing. Maybe she had decided to go in to work after all. He thought of her flushed, feverish face, and of her coughing and sneezing and saying “Shit!” impatiently into her handkerchief. He didn’t think she would have gone in. The truth was, he didn’t think she was strong enough to go in.

He hung up and absently removed his quarter from the slot when it clicked back. He went out, jingling the change in his hand. When he saw a cab he hailed it, and as the cab pulled back into the flow of traffic it began to spatter rain.

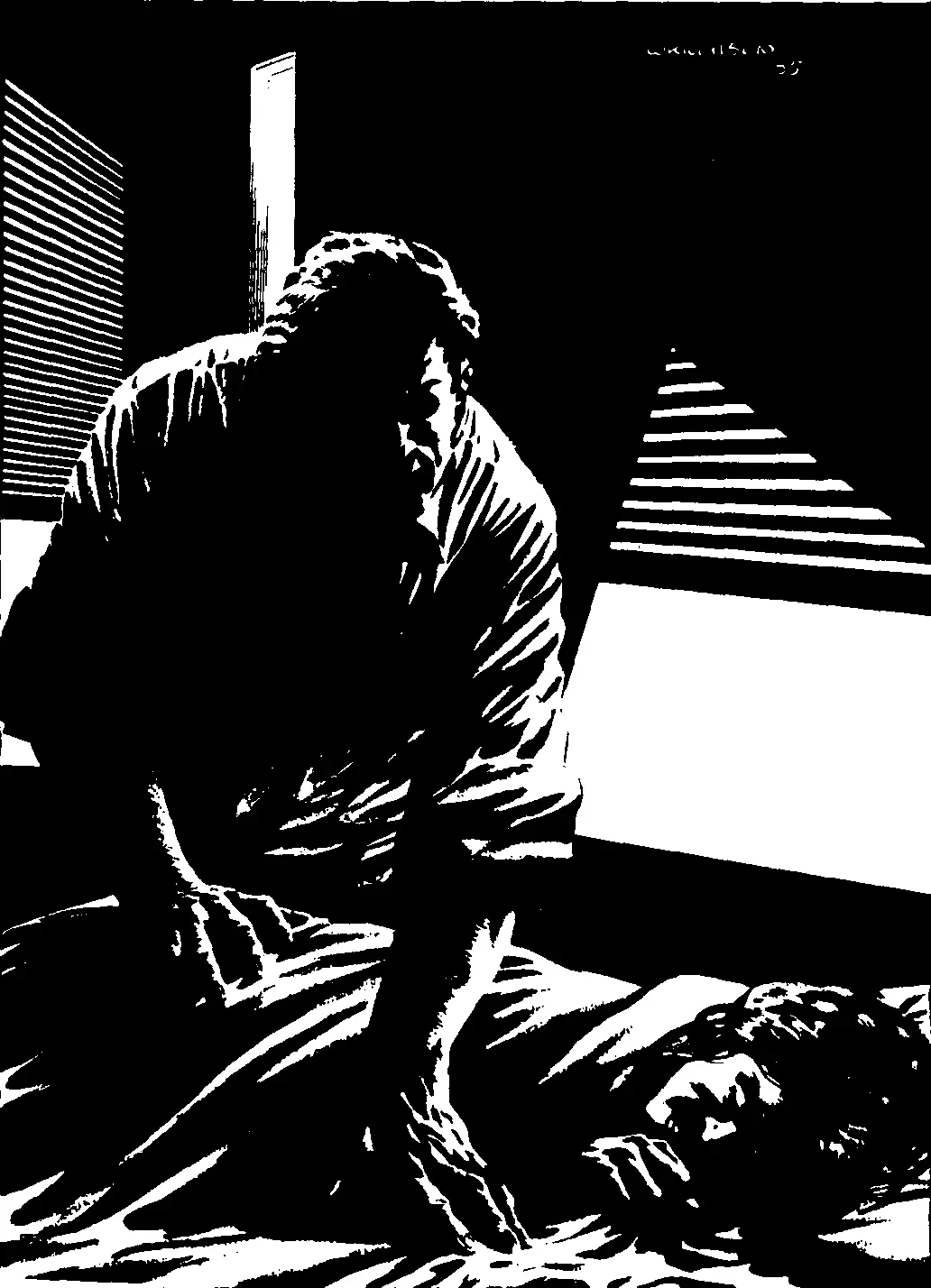

The door was locked and after knocking two or three times he was sure the apartment was empty. He had rapped loud enough to make someone on the floor above rap back, like an exasperated ghost. But he would have to go in and make sure, and he didn’t have a key. He turned to go down the stairs to Mr. Freeman’s apartment, and that was when he heard the low groan from behind the door.

There were three different locks on his mother’s door, but she was indifferent about using them all in spite of her obsession with the Puerto Ricans. Larry hit the door with his shoulder and it rattled loudly in its frame. He hit it again and the lock gave. The door swung back and banged off the wall.

“Mom?”

That groan again.

The apartment was dim; the day had grown dark very suddenly, and now there was thick thunder and the sound of rain had swelled. The living room window was half open, the white curtains bellying out over the table, then being sucked back through the opening and into the airshaft beyond. There was a glistening wet patch on the floor where the rain had come in.

“Mom, where are you?”

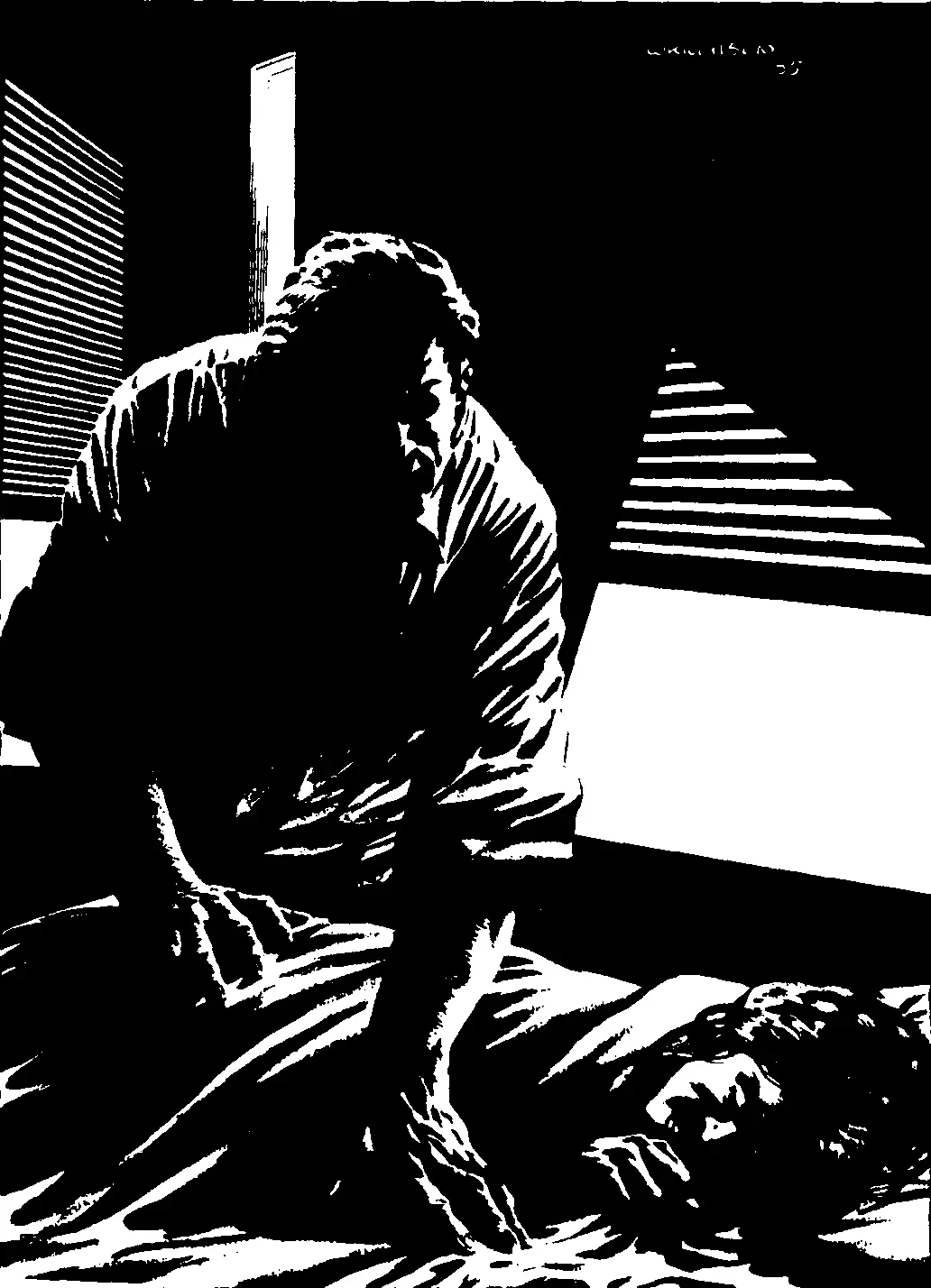

A louder groan. He went through into the kitchen, and thunder rumbled again. He almost tripped over her. She was lying on the floor, half in and half out of her bedroom.

“Mom! Jesus, Mom!”

She tried to roll over at the sound of his voice, but only her head would move, pivoting on the chin, coming to rest on the left cheek. Her breathing was stertorous and clogged with phlegm. But the worst thing, the thing he never forgot, was the way her visible eye rolled up to look at him, like the eye of a hog in a slaughtering pen. Her face was bright with fever.

“Larry?”

“Going to put you on your bed, Mom.”

He bent, locking his knees fiercely against the trembling that wanted to start up in them, and got her in his arms. Her housecoat fell open, revealing a wash-faded nightgown and fishbelly-white legs sewn with puffy varicose veins. Her heat was immense. That terrified him. No one could remain so hot and live. Her brains must be frying in her head.

As if to prove this, she said querulously: “Larry, go get your father. He’s in the bar.”

“Be quiet,” he said, distraught. “Just be quiet and go to sleep, Mom.”

“He’s in the bar with that photographer!” she said shrilly into the palpable afternoon darkness, and thunder cracked viciously outside. Larry’s body felt as if it was coated with slowly running slime. A cool breeze was moving through the apartment, coming from the half-open window in the living room. As if in response to it, Alice began to shiver and the flesh of her arms humped up in gooseflesh. Her teeth clicked. Her face was a full moon in the bedroom’s semidarkness. Larry scrambled the covers down, put her legs in, and pulled the blankets up to her chin. Still she shivered helplessly, making the top blanket quiver and quake. Her face was dry and sweatless.

“ You go tell him I said come outta there! ” she cried, and then was silent, except for the heavy bronchial sound of her breathing.

He went back into the living room, approached the telephone, then detoured around it. He shut the window with a bang and then went back to the phone.

The books were on a shelf underneath the little table it sat on. He looked up the number of Mercy Hospital and dialed it while more thunder cracked outside. A stroke of lightning turned the window he’d just closed into a blue and white X-ray plate. In the bedroom his mother screamed breathlessly, chilling his blood.

The phone rang once, there was a buzzing sound, then a click. A mechanically bright voice said: “This is a recording made at Mercy General Hospital. Right now all of our circuits are busy. If you will hold, your call will be taken as soon as possible. Thank you. This is a recording made at Mercy General Hospital. At the time of your call—”

Читать дальше