"But you aren't comfortable in your mind about any 'allergy attack' in this case," Velvelig said shrewdly, and chan Tergis shook his head again.

"No, Sir, I'm not," he admitted. "Lamir's receiving range is shorter than his transmission range, that's why he's closer to Fort Brithik than to us. He'd have to be seriously ill to be unable to reach me with a transmission from his end, especially if he tranced to do it. And he's never let better than three days go by without sending at least a test message."

"Is it possible he's come down with something a bit more serious than an allergy attack? Something that came on quickly enough that he didn't realize he needed to get a message off to you before it put him out of commission?"

"Certainly it's possible. Probable, though?" Chan Tergis shrugged. "I'd have to say I don't think it's very likely."

"I see," Velvelig said again.

"This is a prime example of why we shouldn't have Voice relay stations with only single Voices assigned to them," chan Tergis said. "If one Voice goes down, for any reason, there ought to be another one ready to back him up the way they do in the inner and middle rings. And we wouldn't have had to play musical chairs with Baulwan and chan Lyrosk this way, either. To be honest, we've virtually built communications breakdowns into the system ourselves simply by stretching our supply of Voices so thin."

"I agree with you, Senior-Armsman," Velvelig said dryly. "Unfortunately, there are those nasty budgetary considerations. And, let's face it, the supply of Voices willing to go haring off into the wilderness is limited-very limited."

"I realize that, Sir." Chan Tergis' tone held a hint of what might almost have been apology, and Velvelig's use of his own rank had apparently jogged his mental elbow into remembering the proper form of military address when speaking to a superior … for the moment, at least. But his expression was also stubborn.

"I'm not saying there weren't what seemed to be perfectly good reasons for accepting the kind of stretch we're working with out here," he continued. "I'm only saying that we've just found out why what looked like good reasons really weren't. Not now."

"A point which I'm quite sure hasn't been lost on First Director Limana and the rest of the Portal Authority," Velvelig said. "In the meantime, we're still left with our uncertainty about the reasons for the silence coming from down-chain."

Chan Tergis nodded, and Velvelig inhaled deeply.

"Very well, Senior-Armsman. I want you to continue trying to reach Voice Ilthyr. But I also want you to send a message up-chain. I want higher authority informed about this."

"You think something serious is wrong?" Chan Tergis' question came out sounding remarkably like a statement, Velvelig thought, and shrugged.

"I don't know that I'd say I think something is seriously wrong. But I'm certainly open to the possibility that something may be wrong. It's hard for me to visualize something that could have kept any warning from getting out to us, but in light of what chan Tesh and chan Baskay have been saying, I'm not going to rule anything out, either."

"I'm not exactly in favor of taking any chances, either, Sir, but it's almost three hundred miles from Fort Shaylar to Fort Brithik, and it's another twelve hundred miles from Fort Brithik to Fort Ghartoun. That's the next best thing to sixteen hundred miles of nothing but horse trails and wilderness, and Lamir's relay station is five hundred miles this side of Brithik. I can't think of anything that could cover that much ground in just three days!"

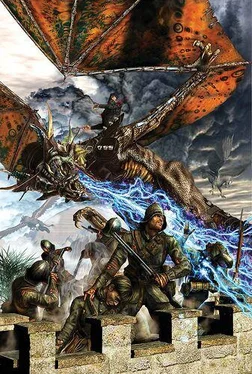

"Neither can I," Velvelig said mildly. "On the other hand, two months ago I couldn't have imagined anything that threw honest-to-gods fireballs or lightning bolts, either. Under the circumstances, it probably wouldn't be a bad idea to accustom ourselves to stretching our mental horizons, don't you think? And if it should happen that for some strange reason we drop off the Voicenet, I'd like to think someone might notice."

"Yes, Sir. I understand."

"Good, Senior-Armsman. Now-" Velvelig made a shooing motion with his right hand "-go do it."

"Now that's a sight for sore eyes, Sir. If you don't mind my saying so."

Platoon-Captain His Grand Imperial Highness Janaki chan Calirath drew rein as they topped out across the modest ridge line, then looked across at Chief-Armsman Lorash chan Braikal with a quizzical expression.

"I don't mind at all, Chief," he said mildly. "In fact, I agree. Although, to be honest, it's not my sore eyes I'm thinking about."

The chief-armsman's mouth twitched, but he'd been an Imperial Marine for seventeen years, and his expression had learned to behave itself … more or less.

"As the Platoon-Captain says, of course, Sir," chan Braikal responded after a moment. "Far be it from me to confuse the Platoon-Captain's anatomical parts."

"I should certainly hope not, Chief." Janaki's voice was admirably severe, but his eyes twinkled, and chan Braikal snorted. Then the noncom's expression turned more serious.

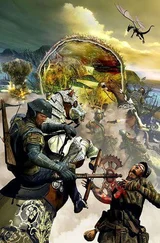

"All joking aside, Sir, I really am glad to see that," he said, waving one hand at the incredible energy raising the thick clouds of dust under the baking sun of the Queriz Depression. Black banners of smoke from the funnels of steam shovels and bulldozers mingled with the dust, hanging in a lung-clogging pall, and they could see the long, gleaming line of steel rails stretching out towards the southern horizon beyond it.

"I am, too," Janaki agreed, and uncased his binoculars. He raised them to his eyes, and the distant scene jumped into sharp focus as he turned the adjusting knob.

There had to be at least a thousand workers immediately visible down there, he reflected, and every one of them was as busy as an entire clan of beavers. Bulldozers and shovels chewed the roadbed out of the bone-dry, mostly flat terrain, rampaging through their self-induced fog of dust like steam- and smokesnorting monsters. Steam-powered tractors followed along behind them on caterpillar treads, dumping heavy loads of gravel for more bulldozers, scrapers, and steamrollers to level into place and tamp firmly.

Then more tractors followed behind, hauling heavy trailers stacked high with railroad ties and rails.

Workers balanced precariously atop the loads tossed ties and rails over the trailers' sides with the easy rhythm of long practice, and each balk of timber, each gleaming length of steel, landed precisely where it was supposed to be.

More workers moved forward, adjusting the ties, setting them into the waiting gravel ballast of the steadily advancing roadbed. Gangs of track-layers followed them, lifting the rails, swinging them into place on the heavy, creosote-soaked ties, holding them there while plate men fished the rail ends, then stood aside while flashing hammers drove the spikes.

The Crown Prince of Ternathia-who was well on his way to becoming the crown prince of all of Sharona-lowered the binoculars and shook his head. This was scarcely the first Trans-Temporal Express railhead he'd ever watched advancing across a virgin universe, but right off the top of his head, he couldn't remember ever seeing such a focused, frenzied, carefully choreographed boil of energy.

And just why should you find that particularly surprising, Janaki? he asked himself sardonically. You've never seen them laying track towards something that looks entirely too much like an inter-universal war, either, have you?

"That sore part of me that isn't eyes is really looking forward to parking itself in a passenger car's seat," he informed chan Braikal as he returned his binoculars to their case. "Of course, after this long in the saddle, my memory of what passenger cars are like has become a bit vague."

"I'm sure it will all come back to the Platoon-Captain," chan Braikal said. "And I hope you won't take this wrongly, Sir, but the main reason I'll be glad to see those passenger cars has more to do with speed than places to sit. The further and faster towards the rear we get these prisoners-and you-the better I'll like it."

Читать дальше