“Boys will be boys,” Sid Feller murmured, sizing up Stag Preston with a cool, promoter’s eye.

“Here he is,” Mandle pontificated, " Stag Preston !”

It was a mixture of disappointed ah’s and damn’s from the youthful crowd, intermingled with applause. The great American tradition of applauding any thing, by habit, not merit.

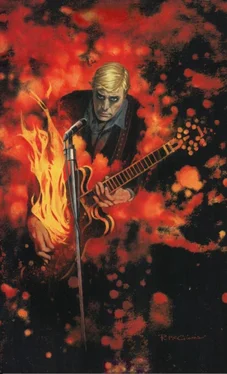

Then Stag Preston came on:

Like Gang Busters…

Like Attila The Hun…

Like Quantrill and all his raiders…

Like Stag Preston under full steam and I’m goin’ all the way and get outta my line of fire because this is it , baby, it with nitro!

He belted out “Car Hop Angel” with a drive that won the kids immediately. It was a good number, combining all the demanded idiosyncrasies of rockabilly, but with style; a little—not too much—imagination; room for vocal tricks; and enough leering suggestiveness in the phrasing to make the hipper ones titter. He went over. Big. Very big.

When he broke, and slid to one knee for the finish, they came up out of their seats as though electrocuted. They stamped and screamed and demanded more, banging their hands together and whistling, clapping the seats of their wooden chairs, hooting. The A&R men’s jaw lines hardened; Sid Feller let a vague smile tilt at the corner of his mouth.

The combo began a soft comp, swaying in on the opening bars of Stag’s flip-side record, “I Don’t Know You Anymore.”

They settled back to silence, bright-eyed, letting him prove himself again.

He sang. Lord, how he sang , Shelly thought, later.

He sang with something more than his gonads. He sang with his … what the hell, use it … his heart. He sang so that every pimply-faced adolescent in that audience knew he was singing about him … about her. About the great affair that had just ended. About the tears in the back seat. About the look of youthful desire. About experiments on summer beaches with the others around the fire toasting the marshmallows, unaware. He sang about every sloppy, inept, melodramatic relationship indulged in by every fifteen, sixteen, seventeen-year-old there. He had it down pat. He had it all right there, and they took it from his extended hands. They didn’t bother to examine it … the smell and the sound and the tough touch of it was right.

When Stag Preston finished that number, his success was a foregone conclusion. The A&R men did not stay for the nine more songs he sang, nor for the fifteen encores.

Fifteen encores, and when he left the stage, the name Stag Preston no longer brought ah or damn to the teen-aged lips. It was the beginning of the underground whisper campaign so necessary to a rock’n’roll singer’s success. Shelly knew it by heart, knew every inch of the self-devouring tapeworm of mouth-to-mouth promotion. As a small time DJ, before his path and Freeport’s had crossed, he had experienced the dynamiting done by flak-merchants. Now he knew what he had to do.

While Stag and the A&R men and Freeport cavorted vocally (Kid, you’ve got it knocked ! You are only the greatest!) in the locker room, Shelly sought out The Ringleaders.

Only Shelly thought of them that way. To Dick Clark they were “his regulars,” the kids who made up the nucleus of his studio audience … the kids who carried the word in phone calls, letters and mimeographed fansheets to other fanatics all over the country. To Anka or Bobby Rydell they were “the kids,” the group from which these teen-idols had but recently risen, and to whom they returned for the most easily identifiable praise and the subversive spreading of fame and adoration. To Shelly they were a million unpaid, deadly effective little PR men and women, scuttling around the countryside without pay or prestige—and with so much power the mind boggled at the concept. The hard little blonde with the kohl around her eyes who showed up every day on American Bandstand; the three Italian boys who boxed in the Golden Gloves and when they weren’t working on construction gangs organized fan clubs for half a dozen press agents; the bespectacled, scrawny girl in Bayonne, New Jersey, who spent all her money on a lithographed poop sheet about Elvis Presley, distributed free to anyone who would send her a four-cent stamp; hundreds of them, the ones who held the reins of influence in their adolescent paws. The ones who swayed public opinion without anyone’s realizing they were doing it. The ones who fed the gossip to local papers, who wrote letters to tv shows demanding their favorite; the dedicated, lonely, stardust-covered ones who would be appalled at the suggestion of accepting the tens of thousands of dollars to which they were entitled for public relations work that could never be done half so well by twenty-grand-a-year men.

These were the line troopers.

These were the informants, the stringers, the busy-bees.

These were the ones Shelly Morgenstern sought out, in that audience, while Stag Preston cinched his future behind the scenes. This was Shelly’s job. Sew them up. Make them feel Stag Preston was one of them, was them in fact. So the postcards would go out the next morning or even that night:

Dear Trudi,

Tonight I heard a great new star. You got to hear him. His name is Stag Preston and he is dreamy. He has only made one record and it isn’t out as yet but when you hear it you will flip on account of he really has that beat. His name is Stag Preston and his song is I Don’t Know You Any More and on the flip side there is Car Hop Angel which really is swinging. I just had to write you so you could tell all the kids in San Francisco. That is about all and how are things with you? Are you still seeing Frank or is that off?

Love, Francine Hasher.

And within a few days the record shops would begin to receive calls for Stag’s pressing, the radio stations would find they were being besieged for a record they had never heard about, the jukebox gangsters would find there was interest in someone named Stag Preston, and how about maybe we buy a piece of this kid, he smells like he’s gonna be a mover.

Then the records would begin to flood out. Whoever did the release would have worked the artists and the photogs and the printing plants overtime to get the flyers and the poop sheets and the labels and the special 45 sleeves ready.

And then…

And then…

Shelly Morgenstern heard the faraway clicking of an adding machine. All those bucks, all that line, a real fine taste—to pay off the Mercedes, to keep Carlene happy (he put the thought of her long, smooth body out of his mind; not now, I’ll tell you when), to get him as far away from the roots and soul of Sheldon Morgenstern as possible.

Mandle had given him a list of half a dozen Ringleaders. He sought them out and drew them aside, playing them like instruments, letting the scent of fame wash over them…

“You’ll be the first Stag Preston fans in the country. Stag’s going to be up there with the biggest of them, and you kids can help. How’d you like that?”

“We get regular letters from Paul Anka when we push his records,” one sharp-eyed girl remarked.

Shelly grinned becomingly. “Honey, Stag is a de mon at writing letters. And he’s got a bug for taking pictures all over the place. He’ll not only send you letters, but some good pictures, too.”

They purred.

“Bob Mandle will be plugging Stag from now on; he thinks he’s great, kids, and we need your help, too. Now how about it?”

They didn’t sing the “Battle Hymn of the Republic," but they might as well have … they were Shelly’s gang. He owned them. They were, in the parlance, in his pocket.

If you like carrying grenades with the pins pulled.

Читать дальше