Cornell Woolrich!

Jeeeezus, if Hans had said I was sitting next to Ernest fucking Hemingway it couldn’t have collapsed me more thoroughly. Bertrand Russell, Bob Feller, Dick Bong, Walt Kelly … all my heroes … it wouldn’t have gotten to me half as much. Cornell goddam Woolrich! I damn near fainted.

“But I thought he’d died years ago,” I said.

They laughed at me. He was old, no doubt about that, but he was very much alive. He wasn’t writing any more; his mother — whom he’d lived with through all of his adult life, in a resident hotel in Manhattan — had recently died; and he was just getting out and around.

I was flabbergasted. I’d sat and talked with Cornell Woolrich, one of my earliest writing heroes, and hadn’t even known it. I wanted to find him in that crowded apartment and just be near him for a while longer.

They were bemused by my goshwow attitude, but they were also a little perplexed. Hans said, “I do not remember seeing him here. Where is he?”

And I led them back to the easy chair in the far rear corner of the room. And he was gone. And he was nowhere in the apartment. And no one else had talked to him. And I never saw him again. And be died soon after that night, I learned later.

To this day, I’ve felt there was something strange and pivotal in my meeting with Woolrich. He could not possibly have known who I was, nor could he have much cared. But we talked writing, and I was the only one who saw or talked to him that night. I’m sure of that. Don’t ask me how I know, I cannot give you a rational explanation; and I firmly do not believe in ghosts or astrology or UFO’s or much else of the nonsense gobbledygook that people substitute for the ability to handle reality. But from the time I left him in that easy chair till the moment I went back to find him, I was right in front of the only exit from that apartment and there was no way he could have gotten past me without my seeing him.

For years I thought about that night in New York.

And one afternoon I sat down and wrote the first two pages of a story titled “Tired Old Man,” in which I thought I would fictionalize that evening, and (as I had with Leiber) pay homage to a writer whose words had so deeply affected me.

But the two pages went into the idea file, unresolved. They stayed there for six years, until earlier this month, June 1975. I was in the process of writing an original story for this book, and had started on another idea I’d had a while back, and in looking for the note for that story (which will be included in SHATTERDAY, coming from Pyramid in three months), I chanced upon the two pages of “Tired Old Man.” And without my even knowing why, or realizing what I was doing, in a lunatic move that could only make this book late to my publisher and late to the printer and late to the on-sale date and late to your hands, I took up the writing of the story as if it had been six years earlier.

And as impossible as it had been for me to write it six years before, because I hadn’t known how to write it six years before, it was that easy for me to start with the very next sentence — as if I’d written the last word of the previous sentence only a moment earlier, not six years before — and go all the way through to the end in one sitting.

Marki Strasser in the story is Cornell Woolrich.

At least, in the impetus for the character. It isn’t supposed to be Woolrich in the story, it’s … well … that’s what the story is about, as you’ll see … but I wanted you to know how “Tired Old Man” came to be written; in answer to the people who always ask me, “Where do you get your ideas?”

And that brings me, at last, to the end of this introduction. I assure you when I started, some 42 typewritten pages earlier, I had no idea I’d run on like this.

But it’s nice getting together with you like this, if for no other reason than to keep out the darkness for just a few minutes longer. And in the course of writing these words, I went back and read the section of BLACK ALIBI in which the young girl, Teresa Delgado, is stalked and killed by the black panther as she screams for her mother to open the door and let her in. And it still conjures up the stark terror I first felt when I saw it in a Val Lewton film at the age of nine.

And for giving rebirth to that “tolerable terror” I thank you. We’ve got to get together again like this.

That is, if you get through the night.

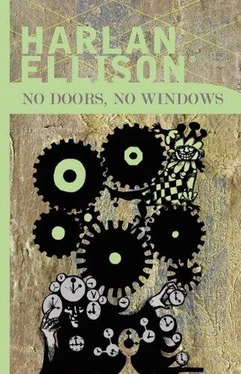

HARLAN ELLISON

Los Angeles

One: The Whimper of Whipped Dogs

On the night after the day she had stained the louvered window shutters of her new apartment on East 52nd Street, Beth saw a woman slowly and hideously knifed to death in the courtyard of her building. She was one of twenty-six witnesses to the ghoulish scene, and, like them, she did nothing to stop it.

She saw it all, every moment of it, without break and with no impediment to her view. Quite madly, the thought crossed her mind as she watched in horrified fascination, that she had the sort of marvelous line of observation Napoleon had sought when he caused to have constructed at the Comédie-Française theaters, a curtained box at the rear, so he could watch the audience as well as the stage. The night was clear, the moon was full, she had just turned off the 11:30 movie on channel 2 after the second commercial break, realizing she had already seen Robert Taylor in Westward the Women , and had disliked it the first time; and the apartment was quite dark.

She went to the window, to raise it six inches for the night’s sleep, and she saw the woman stumble into the courtyard. She was sliding along the wall, clutching her left arm with her right hand. Con Ed had installed mercury-vapor lamps on the poles; there had been sixteen assaults in seven months; the courtyard was illuminated with a chill purple glow that made the blood streaming down the woman’s left arm look black and shiny. Beth saw every detail with utter clarity, as though magnified a thousand power under a microscope, solarized as if it had been a television commercial.

The woman threw back her head, as if she were trying to scream, but there was no sound. Only the traffic on First Avenue, late cabs foraging for singles paired for the night at Maxwell’s Plum and Friday’s and Adam’s Apple. But that was over there, beyond. Where she was, down there seven floors below, in the courtyard, everything seemed silently suspended in an invisible force-field.

Beth stood in the darkness of her apartment, and realized she had raised the window completely. A tiny balcony lay just over the low sill; now not even glass separated her from the sight; just the wrought-iron balcony railing and seven floors to the courtyard below.

The woman staggered away from the wall, her head still thrown back, and Beth could see she was in her mid-thirties, with dark hair cut in a shag; it was impossible to tell if she was pretty: terror had contorted her features and her mouth was a twisted black slash, opened but emitting no sound. Cords stood out in her neck. She had lost one shoe, and her steps were uneven, threatening to dump her to the pavement.

The man came around the corner of the building, into the courtyard. The knife he held was enormous — or perhaps it only seemed so: Beth remembered a bone-handled fish knife her father had used one summer at the lake in Maine: it folded back on itself and locked, revealing eight inches of serrated blade. The knife in the hand of the dark man in the courtyard seemed to be similar.

The woman saw him and tried to run, but he leaped across the distance between them and grabbed her by the hair and pulled her head back as though he would slash her throat in the next reaper-motion.

Читать дальше