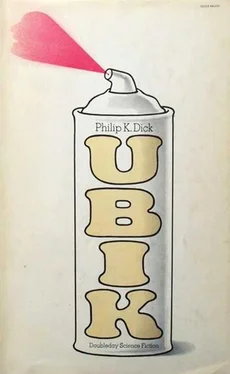

It takes more than a bag to seal in food flavor; it takes Ubik plastic wrap—actually four layers in one. Keeps freshness in, air and moisture out. Watch this simulated test.

“Do you have a cigarette?” Joe said. His voice shook, but not from weariness. Nor from cold. Both had gone. I’m tense, be said to himself. But I’m not dying. That process has been stopped by the Ubik spray.

As Runciter said it would, he remembered, in his taped TV commercial. If I could find it I would be all right; Runciter promised that. But, he thought somberly, it took a long time. And I almost didn’t get to it.

“No filter tips,” Runciter said. “They don’t have filtration devices on their cigarettes in this backward, no-good time period.” He held a pack of Camels toward Joe. “I’ll light it for you.” He struck a match and extended it.

“It’s fresh,” Joe said.

“Oh hell, yes. Christ, I just now bought it downstairs at the tobacco counter. We’re a long way into this. Well past the stage of clotted milk and stale cigarettes.” He grinned starkly, his eyes determined and bleak, reflecting no light. “In it,” he said, “not out of it. There’s a difference.” He lit a cigarette for himself too; leaning back, he smoked in silence, his expression still grim. And, Joe decided, tired. But not the kind of tiredness that he himself had undergone, Joe said, “Can you help the rest of the group?”

“I have exactly one can of this Ubik. Most of it I had to use on you.” He gestured with resentment; his fingers convulsed in a tremor of unresigned anger. “My ability to alter things here is limited. I’ve done what I could.” His head jerked as he raised his eyes to glare at Joe. “I got through to you—all of you—every chance I could, every way I could. I did everything that I had the capacity to bring about. Damn little. Almost nothing.” He lapsed then into smoldering, brooding silence.

“The graffiti on the bathroom walls,” Joe said. “You wrote that we were dead and you were alive.”

“I am alive,” Runciter rasped.

“Are we dead, the rest of us?”

After a long pause, Runciter said, “Yes.”

“But in the taped TV commercial—”

“That was for the purpose of getting you to fight. To find Ubik. It made you look and you kept on looking too. I kept trying to get it to you, but you know what went wrong; she kept drawing everyone into the past—she worked on us all with that talent of hers. Over and over again she regressed it and made it worthless.” Runciter added, “Except for the fragmentary notes I managed to slip to you in conjunction with the stuff.” Urgently, he pointed his heavy, determined finger at Joe, gesturing with vigor. “Look what I’ve been up against. The same thing that got all of you, that’s killed you off one by one. Frankly, it’s amazing to me that I was able to do as much as I could.”

Joe said, “When did you figure out what was taking place? Did you always know? From the start?”

“ ‘The start,’ ” Runciter echoed bitingly. “What’s that mean? It started months or maybe even years ago; god knows how long Hollis and Mick and Pat Conley and S. Dole Melipone and G. G. Ashwood have been hatching it up, working it over and reworking it like dough. Here’s what happened. We got lured to Luna. We let Pat Conley come with us, a woman we didn’t know, a talent we didn’t understand—which possibly even Hollis doesn’t understand. An ability anyhow connected with time reversion; not, strictly speaking, the ability to travel through time… for instance, she can’t go into the future. In a certain sense, she can’t go into the past either; what she does, as near as I can comprehend it, is start a counter-process that uncovers the prior stages inherent in configurations of matter. But you know that; you and Al figured it out.” He ground his teeth with wrath. “Al Hammond—what a loss. But I couldn’t do anything; I couldn’t break through then as I’ve done now.”

“Why were you able to now?” Joe asked.

Runciter said, “Because this is as far back as she is able to carry us. Normal forward flow has already resumed; we’re again flowing from past into present into future. She evidently stretched her ability to its limit. 1939; that’s the limit. What she’s done now is shut off her talent. Why not? She’s accomplished what Ray Hollis sent her to us to do.”

“How many people have been affected?”

“Just the group of us who were on Luna there in that subsurface room. Not even Zoe Wirt. Pat can circumscribe the range of the field she creates. As far as the rest of the world is concerned, the bunch of us took off for Luna and got blown up in an accidental explosion; we were put into cold-pac by solicitous Stanton Mick, but no contact could be established—they didn’t get us soon enough.”

Joe said, “Why wouldn’t the bomb blast be enough?”

Lifting an eyebrow, Runciter regarded him.

“Why use Pat Conley at all?” Joe said. He sensed, even in his weary, shaken state, something wrong. “There’s no reason for all this reversion machinery, this sinking us into a retrograde time momentum back here to 1939. It serves no purpose.”

“That’s an interesting point,” Runciter said; he nodded slowly, a frown on his rugged, stony face. “I’ll have to think about it. Give me a little while.” He walked to the window, stood gazing out at the stores across the street.

“It strikes me,” Joe said, “that what we appear to be faced with is a malignant rather than a purposeful force. Not so much someone trying to kill us or nullify us, someone trying to eliminate us from functioning as a prudence organization, but—” He pondered; he almost had it. “An irresponsible entity that’s enjoying what it’s doing to us. The way it’s killing us off one by one. It doesn’t have to prolong all this. That doesn’t sound to me like Ray Hollis; he deals in cold, practical murder. And from what I know about Stanton Mick—”

“Pat herself,” Runciter interrupted brusquely; he turned away from the window. “She’s psychologically a sadistic person. Like tearing wings off flies. Playing with us.” He watched for Joe’s reaction.

Joe said, “It sounds to me more like a child.”

“But look at Pat Conley; she’s spiteful and jealous. She got Wendy first because of emotional animosity. She followed you all the way up the stairs just now, enjoying it; gloating over it, in fact.”

“How do you know that?” Joe said. You were waiting here in this room, he said to himself; you couldn’t have seen it. And—how had Runciter known he would come to this particular room?

Letting out his breath in a ragged, noisy rush, Runciter said, “I haven’t told you all of it. As a matter of fact…” He ceased speaking, chewed his lower lip savagely, then abruptly resumed, “What I’ve said hasn’t been strictly true. I don’t hold the same relationship to this regressed world that the rest of you do; you’re absolutely right: I know too much. It’s because I enter it from outside, Joe.”

“Manifestations,” Joe said.

“Yes. Thrust down into this world, here and there. At strategic points and times. Like the traffic citation. Like Archer’s—”

“You didn’t tape that TV commercial,” Joe said. “That was live.”

Runciter, with reluctance, nodded.

“Why the difference,” Joe said, “between your situation and ours?”

“You want me to say?”

“Yes.” He prepared himself, already knowing what he would hear.

“I’m not dead, Joe. The graffiti told the truth. You’re all in cold-pac and I’m—” Runciter spoke with difficulty, not looking directly at Joe. “I’m sitting in a consultation lounge at the Beloved Brethren Moratorium . All of you are interwired, on my instructions; kept together as a group. I’m out here trying to reach you. That’s where I am when I say I’m outside; that’s why the manifestations, as you call them. For one week now I’ve been trying to get you all functioning in half-life, but—it isn’t working. You’re fading out one by one.”

Читать дальше