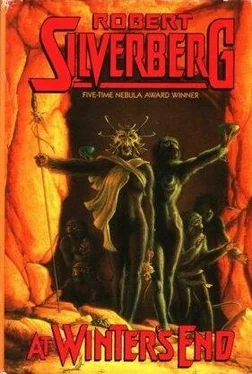

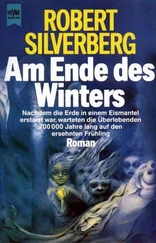

At Winter’s End

by Robert Silverberg

For Terry Carr, who was here for the beginning of this one, though not the end

An axe-age, a sword-age,

shields shall be sundered;

A wind-age, a wolf-age,

ere the world falls.

The sun turns black,

Earth sinks in the sea,

The hot stars down

from heaven are whirled;

Fierce grows the steam

and the life-feeding flame

Till fire leaps high

about heaven itself.

— Elder Edda

Everyone on Earth for a million years or more had known that the death-stars were coming, that the Great World was doomed. One could not deny that; one could not hide from that. They had come before and surely they would come again, for their time was immutable, every twenty-six million years, and their time had come ‘round once more. One by one they would crash down terribly from the skies, falling without mercy for thousands or even hundreds of thousands of years, bringing fire, darkness, dust, smoke, cold, and death: an endless winter of sorrows. Each of the peoples of Earth addressed its fate in its own fashion, for genetics is destiny — even, in a strange way, for life-forms that have no genes. The vegetals and the sapphire-eyes people knew that they would not survive, and they made their preparations accordingly. The mechanicals knew that they could survive if they cared to, but they did not care to. The sea-lords understood that their day was done and they accepted that. The hjjk-folk, who never yielded any advantage willingly, expected to come through the cataclysm unharmed, and set about making certain of that.

And the humans— the humans—

1

The Hymn of the New Springtime

It was a day like no day that had ever been in all the memory of the People. Sometimes half a year or more might go by in the cocoon where the first members of Koshmar’s little band had taken refuge against the Long Winter seven hundred centuries ago, and there would be not one single event worthy of entering in the chronicles. But that morning there were three extraordinary happenings within the span of an hour, and after that hour life would never again be the same for Koshmar and her tribe.

First came the discovery that a ponderous phalanx of ice-eaters was approaching the cocoon from below, out of the icy depths of the world.

It was Thaggoran the chronicler who came upon them. He was the tribe’s old man: it was his title as well as his condition. He had lived far longer than any of the others. As keeper of the chronicles it was his privilege to live until he died. Thaggoran’s back was bowed, his chest was sunken and hollow, his eyes were forever reddened at the rims and brimming with fluid, his fur was white and grizzled with age. Yet there was vigor in him and much force. Thaggoran lived daily in contact with the epochs gone by, and it was that, he believed, which sustained and preserved him: that knowledge of the past cycles of the world, that connection with the greatness that had flourished in the bygone days of warmth.

For weeks Thaggoran had been wandering in the ancient passageways below the tribal cocoon. Shinestones were what he sought, precious gems of high splendor, useful in the craft of divination. The subterranean passageways in which he prowled had been carved by his remote ancestors, burrowing this way and that through the living rock with infinitely patient labor, when they first had come here to hide from the exploding stars and black rains that destroyed the Great World. No one in the past ten thousand years had found a shinestone in them. But Thaggoran had dreamed three times this year that he would add a new one to the tribe’s little store of them. He knew and valued the power of dreams. And so he went prowling in the depths almost every day.

He moved now through the deepest and coldest tunnel of all, the one called Mother of Frost. As he crept cautiously on hands and knees in the darkness, searching with his second sight for the shinestones that he hoped were embedded in the walls of the passageway somewhere close ahead, he felt a sudden strange tingling and trembling, a feathery twitching and throbbing. The sensation ran through the entire length of his sensing-organ, from the place at the base of his spine where it sprouted from his body all the way out to its tip. It was the sensation that came from living creatures very near at hand.

Swept by alarm, he halted at once and held himself utterly still.

Yes. He felt a clear emanation of life nearby: something huge turning and turning below him, like a thick sluggish auger drilling through stone. Something alive, here in these cold lightless depths, roaming the mountain’s bleak dark heart.

“Yissou!” he muttered, and made the sign of the Protector. “Emakkis!” he whispered, and made the sign of the Provider. “Dawinno! Friit!”

In awe and fear Thaggoran put his cheek to the tunnel’s rough stone floor. He pressed the pads of his fingers against the chilly rock. He aimed his second sight outward and downward. He swept his sensing-organ from side to side in a wide arc.

Stronger sensations, undeniable and incontrovertible, came flooding in. He shivered. Nervously he fingered the ancient amulet dangling on a cord about his throat.

A living thing, yes. Dull-witted, practically mindless, but definitely alive, throbbing with hot intense vitality. And not at all far away. It was separated from him, Thaggoran perceived, by nothing more than a layer of rock a single arm’s-length wide. Gradually its image took form for him: an immense limbless thick-bodied creature standing on its tail within a vertical tunnel scarcely broader than itself. Great black bristles thicker than a man’s arm ran the length of its meaty body, and deep red craters in its pale flesh radiated powerful blasts of nauseating stench. It was moving up through the mountain with inexorable determination, cutting a path for itself with its broad stubby boulderlike teeth: gnawing on rock, digesting it, excreting it as moist sand at the far end of a massive fleshy body thirty man-lengths long.

Nor was it the only one of its kind making the ascent. From the right and the left now Thaggoran pulled in other heavy pulsing emanations. There were three of the great beasts, five, maybe a dozen of them. Each was confined in its own narrow tunnel, each embarked upon an unhurried journey upward.

Ice-eaters, Thaggoran thought. Yissou! Was it possible?

Shaken, astounded, he crouched motionless, listening to the pounding of the huge animals’ souls.

Yes, he was certain of it now: surely these were ice-eaters moving about. He had never seen one — no one alive had ever seen an ice-eater — but he carried a clear image of them in his mind. The oldest pages of the tribal chronicles told of them: vast creatures that the gods had called into being in the first days of the Long Winter, when the less hardy denizens of the Great World were perishing of the darkness and the cold. The ice-eaters made their homes in the black deep places of the earth, and needed neither air nor light nor warmth. Indeed they shunned such things as if they were poisons. And the prophets had said that a time would come at winter’s end when the ice-eaters would begin to rise toward the surface, until at last they emerged into the bright light of day to meet their doom.

Now, it seemed, the ice-eaters had commenced their climb. Was the endless winter at last reaching its end, then?

Perhaps these ice-eaters merely were confused. The chronicles testified that there had been plenty of false omens before this. Thaggoran knew the texts well: the Book of the Unhappy Dawn, the Book of the Cold Awakening, the Book of the Wrongful Glow.

But it made little difference whether this was the true omen of spring or merely another in the long skein of tantalizing disappointments. One thing was sure: the People would have to abandon their cocoon and go forth into the strangeness and mystery of the open world.

Читать дальше