Doc, nearest to Margo’s line of fire, waltzed around with arm outstretched, as if doing a dance, took three long steps down the slope, and managed to check himself with his feet against a rock ridge three inches high.

Hunter ran to Margo, grabbed the gray pistol with one hand and pulled her finger off the trigger with the other, shouting: “It’s only me!” in her face.

Only then did she stop screaming her killer’s scream to gasp to him a fiendishly grinning, “Uh-huh.”

The Ramrod ran forward toward Ida.

Harry McHeath knelt by Wojtowicz, who was saying: “Wow, oh wow!” Then: “Hell, kid, I was planning on dropping after the first shot, anyhow. They just creased my shoulder — I think. Better we look.”

Doc came loping up to Margo and Hunter, demanding: “My God, what is that gun? I got an arm in the beam edge, and it was like I was throwing the hammer and forgot to let go of it.”

Margo said rapidly to Hunter: “You don’t have to worry about it being out of power. It’s still half-charged — see, the violet line, right there.”

Doc said: “Let me—” and then suddenly snapped erect and quickly stared around him. “McHeath,” he shouted, “bring me Wojtowicz’s gun! Rama Joan, look after Wojtowicz. Hixon, get Hanks’ gun — if that hero cares to give it up. Ross, give Margo back her pistol. She knows how to use it. Margo, you and I are going to reconnoiter this area until we’re sure there’s no more vermin. Get on my left hand and shoot anything with a gun that isn’t one of us, but watch how you swing that beam.”

Margo, who had gone very pale, started to grin again and placed herself by Doc as directed, assuming a wary half-crouch. Wanda, coming up to help the Ramrod revive Ida, took one look at Margo and shrank away from her.

The Little Man said thoughtfully: “I really think it was the Black Dahlia killer, but now we’l probably never know what he looked like. Why, we might even have recognized him.”

Wojtowicz, wincing as Rama Joan ripped his bloody shirt off his shoulder with her teeth, snarled up at Doddsy: “Oh, nuts!”

Rama Joan pushed blood off her lips with her tongue and said quietly: “Fetch your first-aid kit, Mr. Dodd.”

Doc took the gun McHeath offered him, threw a fresh cartridge into the chamber and started up the slope, saying to Margo: “Come on, while there’s still light. We’ve got to secure our camp site.”

Barbara Katz suppressed a wince as the big policeman shoved his head and flashlight through the back window on her side of the sedan and demanded loudly but unexcitedly: “You niggers steal this car?”

She began to talk rapidly, in the role of secretary-companion to Knolls Kelsey Kettering III, meanwhile sliding her hand back and forth on the window frame to draw the policeman’s attention to the hundred-dollar bill in it, but he only went on shining his flashlight in their faces.

When it stabbed at KKK Barbara realized with a shock that the wrinkle-meshed face did look rather like that of an old darkie. And he had turned almost stuporous again — the heat had been too much for him. But then the little pale blue eyes opened and a cracked but arrogant voice commanded: “Stop shining that thing in my face, you blue-coated idiot!”

This seemed to satisfy the policeman, for he switched off his flash, and Barbara felt the bill drawn smoothly from under her fingers. He took his head out of the window and said good-humoredly: “O.K., I guess you can go on now. But tell me one thing, what do you folks think you’re running away from? Most say high tides, but there’s no hurricane. A couple cars talked about something coming from Cuba. You’re all running like rabbits. It doesn’t make sense.”

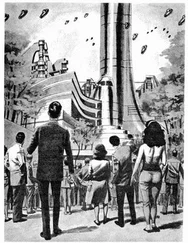

Barbara stuck her head out of the window. “It is the tides,” she insisted. “The new planet is making them.” She looked back east down the road they’d just traveled to where the Wanderer was rising all purple with a yellow monster-shape on it. The glittering spindle of the deformed moon, one end of the spindle foreshortened by the curve of its orbit, might be a sack the monster was carrying.

“Oh, that,” the policeman said, his big face grinning. “That’s something way off in the heavens. It doesn’t matter. I’m talking about things on Earth.”

“But that’s the moon breaking up around it,” she argued.

“Wrong shape for the moon,” he pointed out to her patiently. “The moon’s somewhere else.”

“But the new planet is making high tides,” she pleaded with him. “The first tide wasn’t so bad, but they’ll get higher. Florida’s not more than three hundred feet high anywhere. They may wash straight over it.”

He spread his hands, as if to invoke the testimony of the balmy night fragrant with orange blossoms, and chuckled tolerantly.

Barbara said: “I’m trying to warn you. That planet’s a doom-sign.” He continued to chuckle.

She felt herself seethe with sudden anger. “Well, if nothing that matters is happening,” she demanded, “why are you stopping all cars?”

The grin vanished. “We’re keeping order in Citrus Center,” he said harshly, moving toward the next car in line. “Tell your boy to drive on before I change my mind. Your boss ought to know better than to let his nigger girl talk for him. You college-educated niggers are the worst. They try to teach you science, but you get it all mixed up with your crazy African superstitions.”

They drove north in silence while the Wanderer slowly climbed, and the moon-spindle crawled across it, and the monster changed to a big purple D.

Knolls Kelsey Kettering III began to breathe gaspingly. Hester said: “We got to find him a bed. He got to stretch out.”

Benjy slowed to read a sign. “You are leaving Glades and entering Highlands County.” Suddenly he laughed whoopingly. “That high lands sure sound good!”

But would they be high enough? Barbara wondered.

Richard Hillary woke shivering and aching. He’d pushed aside in his sleep the straw covering him. And through the straw under him, crushed flatly, had mounted the chill of the ground — the chill of the Chiltern Hills, his mind, half sleep-locked, alliterated it. Overhead the strange planet flared, revolved back to its dismal D again. He recalled some of the other faces it had shown — equally ugly faces, looking more like signs or a psychologist’s toys than natural formations — one a bloat-centered X; another, a big yellow bull’s eye in a purple target. Still, it seemed to bulk out more like a true globe how, less like a circular flat signboard. And there was a beauty akin to that of Brancusi’s “Bird in Space” in its curving white half-ring. Could that last conceivably be the moon, as a fellow-trudger had assured him? Surely not. Yet the moon had traveled the sky all last night and where else was the moon now?

He sat up quietly, hugging himself for warmth, rebuttoning his coat collar and turning up the inadequate flap. The straw stack from which he’d taken his bedding was all gone now, and where he’d had at most a dozen comrades when he’d laid down some two hours ago, there were now scores of low straw mounds, each covering one or more sleepers. How quietly they had come — hushing each other, perhaps, as they scooped up and hugged their straw; late arrivers at a sleeping hostel. He envied those huddled in pairs their shared warmth, and he remembered very wistfully the Young Girl of Devizes who had seemed at the time so stupid and coarse. He remembered her sausage-and-mashed, too.

He looked toward the farmhouse where he’d bought a small bowl of soup last night and paid for his straw. Its lights were still on, but the windows were irregularly obscured. He realized with mild amazement that this was because of the people outside crowded together against its walls like bees for warmth. Surely many of the late-comers must have gone hungry; the ready food would be gone like the straw. Or perhaps the farmer’s wife would be baking? He sniffed, but got only a briny smell. Had she opened a barrel of salt beef? But now his mind was wandering foolishly, he told himself.

Читать дальше