“We did at least bring some money with us?” he asked her dryly.

“Oh yes, Mr. Kettering, we took everything from the wall safes,” she assured him, drawing a little comfort from the thickness of the sheaves of bills she could feel through the fabric of her shoulder bag.

The Rolls was slowing down. The last car to pass them was off in the saw grass, its hood half submerged, and the four men who’d been in it were standing shoetop-deep, blocking the roads and waving.

The sight galvanized her. “Don’t slow down!” she cried, grabbing the back of Benjy’s seat “Drive straight through!”

Benjy slowed a little more.

“Do as Miss Katz says, Benjamin,” old KKK ordered him, with a harshness that set him coughing on the next word, which was, “Faster!”

Barbara could see Benjy’s head drawn down into his shoulders and imagined his eyes wincing half shut as he stepped on the gas.

The four men waited until they were two car lengths away, then jumped aside, yelling angrily. It hadn’t been a very good bluff.

She looked back and saw one of them grappling with another, who’d pulled out a gun.

Maybe I did the wrong thing, she thought.

Like hell!

Dai Davies was sitting on top of the bar, watching his candle-girls rill out their last white tears, their maiden-milk, and topple their black wicks in their waxpools and drown. Gwen and Lucy were gone and at this moment Gwyneth. It was a double loss, for he needed their simple warmth and light: the sun had set, and a clear but intense darkness was settling on the great gray watery mead that was all he could see through the diamond-paned windows and door. He’d hoped for a twinkle of lights from far Wales, but it hadn’t come.

The Severn tide had entered the pub some time ago and was now so high he’d tucked his feet up. Two brooms, a mop, a pail, a cigar box, and seven sticks of firewood floated around, circling slowly. He’d fleetingly thought of leaving at one point, and had tucked two pints in his side pockets against that eventuality, but he’d recalled that this was the highest bit of ground for a space around, and the candles had been warm and dear, and now he’d taken on more alcohol, he knew, than would allow sprightly perambulation for a bit.

In any case it was the best sport of all to play King Canute atop a crocodile’s coffin. Two inches more and the tide would stand and turn, he suddenly decided — and loudly ordered the water to do so.

After all, one o’clock, or a bit after that, had been low tide, and so now must be high or near — if this mad salt flooding obeyed any of the old rules at all.

He deeply sniffed at the open fifth in his hand — an American import, Kentucky Tavern by Erskine Caldwell — and watched Eliza shiver and fade and unexpectedly flame up blue and bright.

The lead-webbed windows pressed in at a new surge of the tide. Water gushed through the hole he’d kicked in the door. Then he distinctly felt the bar under him shift a little — in fact, the whole building moved. He took a sour hot swig of the bottle and cried laughingly: “For once it’s the pub that staggers, not Dai!” Then a great seriousness gripped him, and he knew at last exactly what was happening and he cried with a wild pride: “Die, Davies! Die! Deserve your name. But die dashingly. Die with a whiskey bottle in your hand, wafting your love to come again to Cardiff. But…” And then, for once wholly conquering his carping jealousy of Dylan Thomas — “Do not go gentle into that good night. Rage, rage, against the dying of the light.”

And at that very moment, just as Eliza winked out, and the last pearly light seemed to die all over the gray Severn plain, there came a loud knocking at the door, a heavy, slow, authoritative triple knock.

Supernatural fear took hold of him and gave him strength to move against the whiskey, to drop down into the icy water and slosh through it thigh-deep and pull the door open. There, just outside, pressed against the doorframe by the tide, he saw by the dying light of Mary and Jane and Leonie a long, dark, empty skiff.

He sloshed his way back to the bar, the water steadying if impeding him, and gathered three fresh bottles in the crook of his left arm, and on his way back grabbed up the two floating brooms.

The skiff was waiting. He tossed in the brooms, put in the bottles carefully, and then laid his upper body across the boat and grasped the opposite gunwale. He almost blacked out then, but the water was cold on his crotch and he jumped up clumsily and wriggled and pulled until he was in, face down on the wet wood. Then he did black out. His last kick caught the doorframe and sent the skiff moving out and away.

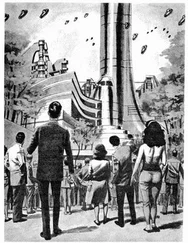

Richard Hillary trudged through the dying twilight ten yards to the side of a road noisy with cars. The cars were moving slowly, almost bumper to bumper, in three lanes abreast so that there was no room at all for traffic in the opposite direction. No use to try for a lift, the cars were all packed with people — and if an empty place should turn up, it would immediately be taken by someone with more obvious claim to it or simply someone nearer the road. Besides, he was walking almost as fast as the cars were moving, rather faster than the majority of the pedestrians.

Cars and folk on foot and he were all somewhere beyond Uxbridge, moving northwest. It had been a relief when the glaring sun had gone down, though every sign of time passing momentarily speeded up the walkers and pushed the vehicles closer together.

Never had Richard experienced such a revolutionary disaster, neither in his life nor in the flow of events around him — not even in the bombing raids remembered from childhood — and all in six hours. First the bus turning north out of the little street flood at Brentford…the driver mum to passengers’ protests except for a reiterated “Traffic Authority orders!"…wireless reports of the larger flood in the heart of London, of the American flying saucer seen in New Zealand and Australia and called a planet…the wireless choked by static just as someone began to recite a list of “civilian directives"…people frantically wondering how to get in touch with families, and he feeling both wounded and relieved that in his own case there was no one who mattered very much. Then the bus stopping at West Middlesex Hospital, with the information that it had been commandeered to move patients…more unsuccessful protests…advice to move northwest by foot, “away from the water"…the refusal to believe…wandering briefly around the grounds of a new brick university…cars and white-faced refugees in greater and greater numbers from the east…the helicopter scattering paper thriftily…a fresh-inked sheet that read only: “ WESTERN MIDDLESEX MOVE TO CHILTERN HILLS. HIGH WATER EXPECTED TWO HOURS AFTER MIDNIGHT.”Finally, joining a northwest trek that grew and grew — becoming part of a dazed and trudging mob.

Richard judged he had been walking about two hours. He was tired; his chin was tucked against his chest, his gaze fixed on his muddy boots. There had been clear signs of recent flooding in a low stretch just overpassed: turbid pools and grass plastered flat. He had no idea of exactly where he was, except that he was well past Uxbridge and had crossed the Colne and the Grand Junction Canal, and that he could see hills far ahead.

The twilight was strangely bright. He almost walked into a clump of people who had halted and were staring back over his head. He turned around to see what they were looking at and there, riding low in the eastern sky, he saw at last the agent of their disaster, looking at least as big as the moon might look in dreams. It was mostly yellow, but with a wide purple bar running down its middle and from the ends of the bar two sharply curving purple arms going out to make a great D. He thought, D for danger, D for disaster, D for destruction. The thing might be a planet, but it didn’t look beautiful — it looked like a garish insignia of the sort you might see in a bomb factory.

Читать дальше