“Seven-thirty, about,” Benjy answered without hesitation. “Hour ago. It have it all on the backs of those calendar sheets.”

“Tear off the top one,” she told him. “What kind of a car does Mr. K have?”

“Only the two Rolls,” he told her. “Limousine and sedan.”

“Get the sedan ready for a long trip,” she told him sharply. “All the extra gas she can carry — take it from the limousine! We’ll need blankets, too, and all Mister K’s medicines and lots of food and more of this coffee in thermos jugs…and a couple of those table-water bottles in the corner!”

They stared at her fascinatedly. Her excitement was contagious, but they were puzzled. “Why for, child?” Hester demanded. Helen started to giggle again.

Barbara looked at them impressively, then said: “Because there’s a high tide coming! As high as this one’s low — and higher!”

“That because of the — Wanderer?” Benjy asked, handing her the sheet she’d asked for.

She nodded decisively as she studied its back. She said: “Mr. K has a smaller telescope. Where would that be?”

’Telescope?” Hester asked with grinning incredulity. She said: “Now, why for — oh, sho, astronomy what you and Mr. K have in common. Now, I expect he put that one — the one he spy on the gals with — back in the gun room.”

“Gun room?” Barbara asked, her eyes brightening. “What about ready cash?”

“It’d be in one of the wall safes,” Hester said, frowning at Barbara just a little.

The saucer students were at last beginning to feel alive again after their ducking and their exhausting race with the waves. The men had built a driftwood fire beside the empty highway near the low concrete bridge at the head of the wash, and everyone was drying out around it, which necessitated considerable comradely trading around of clothes and of the unwetted blankets and stray articles of dress from the truck.

Rama Joan cut down the trousers of her salt-streaked evening clothes to Bermuda shorts, ruthlessly chopped off the tails and half the arms of the coat, replaced the ruined dicky and white tie with the green scarf of her turban, and gathered her red-gold hair in a pony tail. Ann and Doc admired her.

Everybody looked pretty battered. Margo noticed that Ross Hunter appeared trimmer than the other men, then realized it was because, while most of them were getting slightly stubbly cheeks and chins, he simply still had the beard that had made him Beardy.

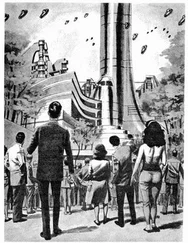

As the sky blued and brightened, their spirits rose and it became just a bit hard to think that all of last night had actually happened, and that a violet and gold planet was at this moment terrorizing Japan, Australia, and the other islands of the half-planet-spanning Pacific Ocean.

But they could see a monster slide blocking the road not two hundred yards north, while Doc pointed out the wreckage of the beach house and the platform lodged against the gleaming fence of Vandenberg Two, little more than a mile away.

“Still,” he said, “humanity’s skepticism about its own experiences grows like mushrooms. How about another affidavit for us all to sign, Doddsy?”

“I’m keeping a journal of events in waterproof ink,” the Little Man retorted briskly. “It’s open to inspection at any time.” He took his notebook and slowly riffled the pages to emphasize that point “If anyone’s memory of events differs from mine, I’ll be happy to make a note of that — providing he’ll initial the divergent recollection.”

Wojtowicz, staring down over the Little Man’s shoulder, said: “Hey, Doddsy, some of those pictures you got of the Wanderer don’t look right to me.”

“I smoothed out the details and made them quite diagrammatic,” the Little Man admitted. “However, I did draw them…from the life. But if you want to make some memory pictures of the new planet — and initial them! — you’re welcome to put them in the book.”

“Not me, I’m no artist,” Wojtowicz excused himself grinningly.

“You’ll be able to check up tonight, Wojtowicz,” Doc said.

“Jeeze, don’t remind me!” the other said, clapping his hand to his eyes and doing a little comedy stagger.

Only the Ramrod remained miserable, sitting apart on the wide bridge-rail and staring hungrily out toward the sea’s rim where the Wanderer had set.

“She chose him” he muttered wonderingly. “I believed, yet I was passed over. He was drawn into the saucer.”

“Never mind, Charlie,” said Wanda, laying her plump hand on his thin shoulder. “Maybe it wasn’t the Empress but only her handmaiden, and she got the orders mixed.”

“You know, that was truly weird, that saucer swooping down on us,” Wojtowicz said to the others. “Just one thing about it — are you sure you saw Paul pulled up into it? I don’t like to say this, but he could have been sucked out to sea, like almost happened to several of us.”

Doc, Rama Joan, and Hunter averred they’d seen it with their own eyes. “I think she was more interested in the cat than Paul,” Rama Joan added.

“Why so?” the Little Man asked. “And why ‘she’?”

Rama Joan shrugged. “Hard to say, Mr. Dodd. Except she looked like a cat herself, and I didn’t notice any external sex organs.”

“Neither did I,” Doc confirmed, “though I won’t say I was peering for them at the time with lewd avidity.”

“Do you think the saucer actually had an inertialess drive — like E. E. Smith’s bergenholms or something?” Harry McHeath asked Doc.

“Have to, I’d think, the way it was jumping around. In a situation like this, science fiction is our only guide. On the other hand—”

Margo took advantage of everyone being engrossed in the conversation to fade back between the bushes in the direction the other women had taken earlier on their bathroom trips. She climbed over a small ridge beside the wash and came out on a boulder-strewn, wide earth ledge about twenty feet above the beach.

She looked around her. She couldn’t see anyone anywhere. She took out from under her leather jacket the gray pistol that had fallen from the saucer. It was the first chance she’d had to inspect it closely. Keeping it concealed while she’d dried her clothes had been an irksome problem.

It was unburnished gray — aluminum or magnesium, by its light weight — and smoothly streamlined. There was no apparent hole in the tapering muzzle for anything material to come out. In front of the trigger-bump was an oval button. The grip seemed shaped for two fingers arid a thumb. In the left side of the grip, away from her palm as she held it in her right hand, was a narrow vertical strip that shone violet five-eighths of its length up, rather like a recessed thermometer.

She gripped the gun experimentally. Just beyond the end of the muzzle she noted a boulder two feet wide sitting on the rim of the ledge. Her heart began to pound. She pointed the gun at the boulder and tapped the trigger. Nothing happened. She pressed it a little harder, then a little harder than that, and suddenly — there was no recoil, but suddenly the boulder was shooting away, and a three-foot bite of ledge with it, to fall almost soundlessly into the sand a hundred feet off, though some of the sand there whooshed up and flew on farther. A breeze blew briefly from behind her. A little gravel rattled down the slope.

She took a gasping breath and a big swallow. Then she grinned. The violet column didn’t look much shorter, if any. She put the gun back inside her jacket, belting the latter a notch tighter. A thoughtful frown replaced her grin.

She climbed back over the top of the ridge, and there on the other side was Hunter, his whiskers showing copper hairs among the brown in the sun’s rays just topping the hills.

Читать дальше