Not for the first time, Richard reflected that this age’s vaunted “communications industry” had chiefly provided people and nations with the means of frightening to death and simultaneously boring to extinction themselves and each other.

He did not inform his seatmate of this insight, but instead turned to the window as the bus slowed for Brentford, surveying that town with his novelist’s eyes, and was rewarded almost at once by a human phenomenon describable as “a scurry of plumbers": he counted three small cars with the insignia of that trade and five men with toolbags or big wrenches, hurrying places. He smiled, thinking how overbuilding invariably brings its digestive troubles.

The bus stopped, not far from the market and the confluence of the canalized Brent with the Thames. Two women climbed in, the one saying loudly to the other: “Yes, I just rang up Mother at Kew and she’s dreadfully upset She says the lawn is afloat.”

It happened quite suddenly then: an up-pooling of brown water from the drains in the street, and a runneling of equally dirty water from the entries of several buildings.

The event struck Richard with peculiar horror because, at a level almost below conscious thought, he saw it as sick, overfed houses discharging, quite independently of the human beings involved with them, the product of their sickness. Architectural diarrhea. He wasn’t thinking at all of how the first sign of a flood is often the backing up of the sewers.

And then there was a scamper of people, and at their heels a curb-to-curb rush of cleaner water, perhaps six inches deep, down the street, washing away the dirty.

It pretty well had to be coming from the Thames. The tidy Thames, Spenser’s “Sweete Themmes.”

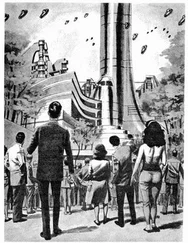

The second and larger installment of destruction was delivered by the Wanderer through the seas covering almost three-quarters of Earth’s surface. This watery film may be cosmically trivial, but it has always been a sort of infinity, of distance and of depth and of power, to the dwellers of Earth. And it has always had its gods: Dagon, Nun, Nodens, Ran, Rigi, Neptune, Poseidon. And the music of the seas is the tides.

The harp of the seas, which Diana the moon goddess strums with rapt solemnity, is strung with bands of salt water miles thick, hundreds of miles wide, thousands of miles long.

Across the great reaches of the Pacific and Indian Oceans stretch the bass strings: from the Philippines to Chile, from Alaska to Colombia, Antarctica to California, Arabia to Australia, Basutoland to Tasmania. Here the deeper notes are sounded, some vibrations lasting a full day.

The Atlantic provides the middle voice, cantabile. Here the tempo is quicker and more regular, and the half-day the measure: the familiar, semidaily tides of Western history. Major vibrating bands link Newfoundland to Brazil, Greenland to Spain, South Africa to the Antarctic.

Where the strings cross they may damp each other out, as at the tidal nodes near Norway and the Windward Islands and at Tahiti, where the sun alone controls the little tides — far-distant Apollo plucking feebler than Diana, forever bringing highs at noon and midnight, lows at sunset and dawn.

The treble of the ocean harp is provided by tidal echoes and re-echoes in bays, estuaries, straits, and seas half landlocked. These shortest strings are often loudest and fiercest, as a violin will dominate a bass viol: the high-mounting tides of Fundy and the Severn Estuary, of Northern France and the Strait of Magellan, of the Arabian and Irish Seas.

Touched by the soft fingers of the moon, the water bands vibrate gently — a foot or two up and down, five feet, ten, rarely twenty, most rarely more.

But now the harp of the seas had been torn from Diana’s and Apollo’s hands and was being twanged by fingers eighty times stronger. During the first day after the Wanderer’s appearance the tides rose and fell five to fifteen times higher and lower than normally and, during the second day, ten to twenty-five, the water’s response swiftly building to the Wanderer’s wild harping. Tides of six feet became sixty; tides of thirty, three hundred — and more.

The giant tides generally followed the old patterns — a different harpist, but the same harp. Tahiti was only one of the many areas on Earth — not all of them far inland — unruffled by the presence of the Wanderer, hardly aware of it except as a showy astronomic spectacle.

The coasts contain the seas with walls which the tides themselves help bite out. In few places are the seas faced with long sweeps of flat land where the tide each day can take miles-long strides landward and back: the Netherlands and Northern Germany, a few other beaches and salt marshes, Northwest Africa.

But there are many flat coasts only a few feet or a few dozen feet above the ocean. There the multiplied tides raised by the Wanderer moved ten, twenty, fifty, and more miles inland. With great heads of water behind them and with narrowing valleys ahead, some moved swiftly and destructively, fronted and topped by wreckage, filled with sand and soil, footed by clanking stones and crashing rocks. At other spots the invasion of the tide was silent as death.

At points of sharp tides and sharp but not very high coastal walls — Fundy, the Bristol Channel, the estuaries of the Seine and the Thames and the Fuchun — spill-overs occurred: great mushrooms of water welling out over the land in all directions.

Shallow continental shelves were swept by the drain of low tides, their sands cascaded into ocean abysses. Deep-sunk reefs and islands appeared; others were covered as deeply. Shallow seas, and gulfs like the Persian, were drained once or twice daily. Straits were grooved deeper. Seawater poured across low isthmi. Counties and countries of fertile fields were salt-poisoned. Herds and flocks were washed away. Homes and towns were scoured flat. Great ports were drowned.

Despite the fog of catastrophe and the suddenness of the astronomic strike, there were prodigies of rescue performed: a thousand Dunkirks, a hundred thousand brave improvisations. Disaster-focused organizations such as coast guards and the Red Cross functioned meritoriously; and some of the preparations for atomic and other catastrophe paid off.

Yet millions died.

Some saw disaster coming and were able to take flight and did. Others, even in areas most affected, did not.

Dai Davies strode across the mucky, littered bottom-sands of the Severn Estuary through the dissipating light fog with the furious energy and concentration of a drunkard at the peak of his alcoholic powers. His clothes and hands were smeared where he’d twice slipped and fallen, only to scramble up and pace on with hardly a check. From time to time he glanced back and corrected his course when he saw his footsteps veering. And from time to time he swigged measuredly from a flat bottle without breaking his stride.

The Somerset shore had faded long since, except for the vaguest loom through the remaining mist of maritime industrial structures upriver toward Avonmouth. Long since there had died away the insincere cheers and uncaring admonitions — “Come back, you daft Welshman, you’ll drown!” — of the pub-mates he’d met this morning.

He chanted sporadically: “Five miles to Wales across the sands, from noon to two while the ebb tide stands,” occasionally varying it with such curses as “Effing loveless Somersets! — I’ll shame ’em!” and “Damned moon-grabbing Yanks!” and such snatches of his half-composed Farewell to Mono as, “Frore Mona in your meteor-skiff…Girlglowing, old as Fomalhaut…Trailing white fingers in my pools…Drawing my waters to and fro…”

There was a faint roaring ahead. A helicopter ghosted by, going downriver, but the roaring remained. Dai crossed a particularly slimy dip in which his shoes sank out of sight and had to be jerked plopping out. He decided it must be Severn channel and that he was now mounting onto the great sandy stretch of bottom known as the Welsh Grounds.

Читать дальше