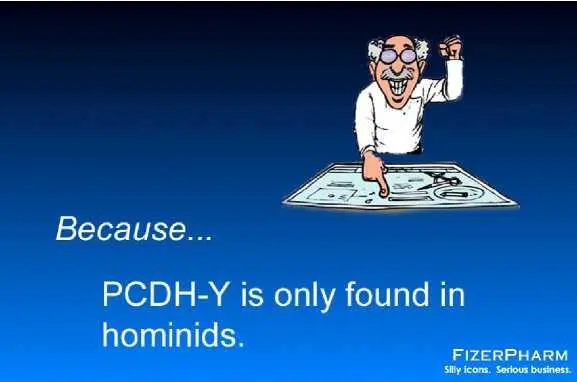

By now you might be wondering why vampires didn’t simply resort to nonhuman prey. It’s not as though Humans were the only available prey species on the planet; why go to all the trouble of evolving these radical, freakish adaptations to keep eating us when they could have just switched to warthogs or zebras? They may well have done so; but the fact that they went to such extreme lengths to accommodate human meat in the diet can only mean that they got something from us that wasn’t available from other species, something essential to their survival. We actually lost a fair number of inmates finding out what it was—you may remember a year or so ago when Amnesty International put out a press release praising Texas for going a whole two months without executing anyone? What they didn’t realise was that a hiatus in executions didn’t necessarily mean a hiatus in mortality. We basically used up death row that year.

And this is what we found: a secondary loss of the ability to synthesize PCDH-Y, a protein responsible for certain aspects of central nervous system development. Since this protein occurs only in other hominids, human prey was an essential component of the vampire diet.

So. What we have here is a very rare subspecies, forced to prey upon its closest kin, which themselves were quite rare (being also near the apex of the pyramid). They were forced to commit a number of evolutionary backflips just to stay in the game. They were easily smart enough to outmaneuver us, but we weren’t their biggest problem. Their biggest problem was just as smart as they were, and just as dependent on the limited supply of human prey. Their biggest problem was other vampires.

This is what happens when you put two vampires in the same room:

Competition for prey evidently ensured that vampires were solitary, very territorial, and mutually antagonistic. Our marketting people had entertained thoughts of teams of vampires working together to solve the world’s ills, but apparently natural selection never taught them to play nicely together. This picture was taken after an early attempt at marketing the cooperative angle, an avenue that we abandoned shortly afterwards

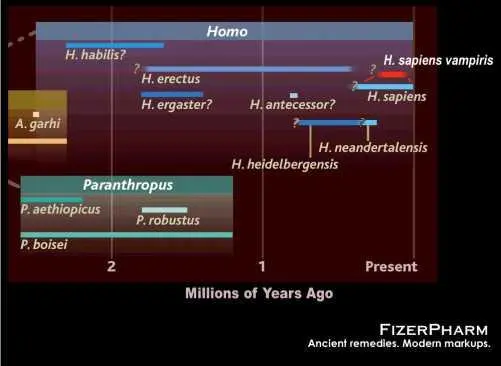

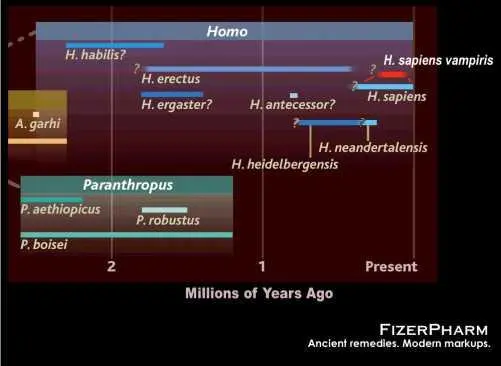

So now you have some idea of what these creatures are. Here’s where they came from: judging by nuclear introns and mitochondrial satellites, we think that vampires split off the human lineage something less than a half-million years ago, and persisted (albeit in small numbers) into the beginning of historical times. We trace their genesis to a paracentric inversion mutation on the Xq21.3 block on the X-chromosome, resulting in functional changes to genes that code for protocadherins. PCDH-Y is a protocadherin, and as I’ve mentioned they play a critical role in the development of the central nervous system. They occur in the headwaters of CNS development, as it were, and a relatively small change far upstream can lead to a whole variety of interrelated cascade effects. These include many of the features you’ve heard about today.

Now I’m not saying that a single mutation made all these improvements in a single lucky step; evolution doesn’t work that way. What I am saying is that a headwater mutation had such a huge impact on so many aspects of CNS development that basically the whole deck of cards got shuffled; suddenly there was far more variation for natural selection to work on, and so vampires could arise relativel quickly from that background chaos.

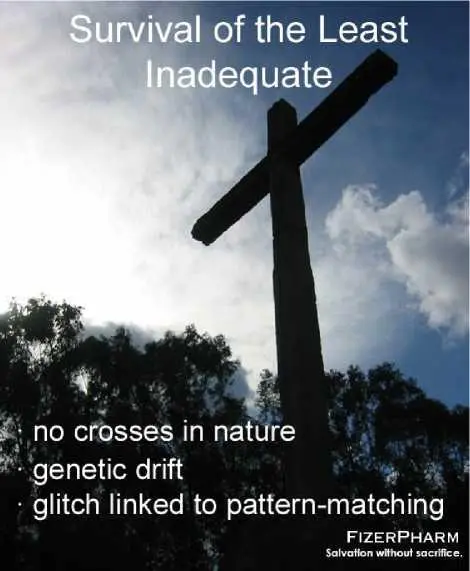

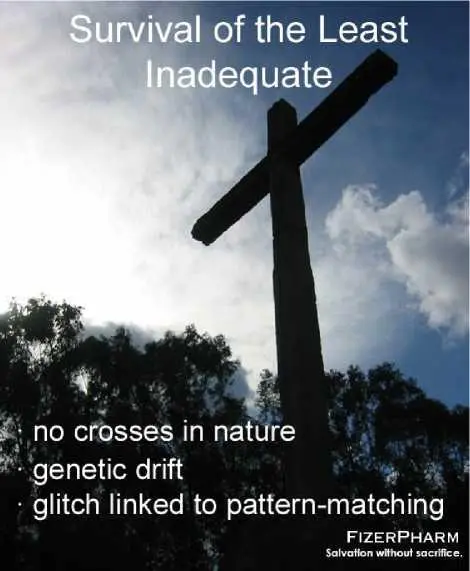

However, natural selection doesn’t optimise anything. "Survival of the fittest" is a profound misnomer: it would be more accurate to say "survival of the least inadequate". It doesn’t matter whether a given adaptation is the best possible solution; all that matters is whether it works better than the competition. Overall, vampires did work better than the competition, but that doesn’t mean they didn’t have a few design flaws. You’ve encountered the two biggies: the broken pathway which forced them to eat other hominids, and the defect that killed Donnie, the so-called crucifix glitch. It is this glitch that doomed them from the moment we developed Euclidean architecture. Vampires would have been barred from approaching any human dwellings that featured quartered windows, supporting crossbeams, and so on. (You can imagine how a resurrected vampire would react to a modern-day office building, with its facades of repeating windowframes. Take my word, it’s not a pretty sight.) And you can be damn sure that our ancestors figured that out pretty early in the game. The cross is not an exclusively Christian icon: it’s been used as a religious symbol back into prehistoric times. Now we know why.

You might wonder how such a lethal trait could get so fixed in the population to begin with. Shouldn’t natural selection have weeded it out sooner? The answer is surprisingly simple: the trait wasn’t lethal, not at first. An aversion to crosses is no disadvantage in a world where crosses don’t exist, and you don’t find many right- angles in nature. Any biology undergrad will tell you, neutrally selective traits can become fixed in small populations through a simple process called genetic drift. In this case the trait wasn’t even neutral: the same crosswiring responsible for the crucifix glitch was also involved in vampiric pattern-matching skills, and that was a trait that natural selection would have actively promoted — right up until the point that their prey discovered geometry.

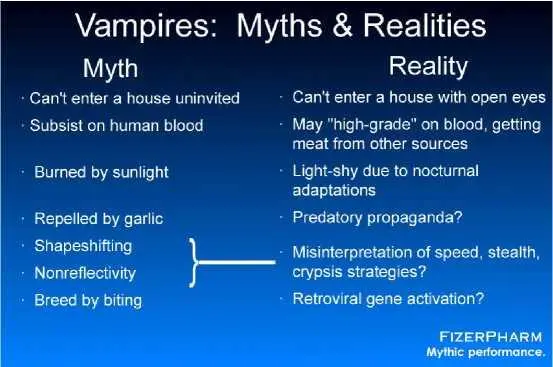

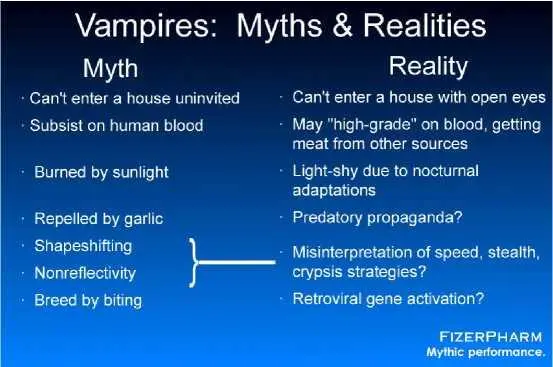

It’s tempting to speculate that this was also the source of the myth that vampires can’t enter someone’s house uninvited. It would be more accurate to say that vampires can’t come into your house unless they keep their eyes closed; and since that would make them extremely vulnerable to attack, they would only be advised to do that when the house’s inhabitants didn’t wish them ill.

We can also draw tentative conclusions about some of the other vampire myths that have sprung up over time. The whole bloodsucking aspect remains an open question: technically vampires are closer to what you might call obligate cannibals, eating human flesh rather than simply drinking the blood. However, given that the only thing they really needed from us was a certain type of protein, it’s theoreticaly possible that a blood diet could meet that need, although they’d have to drink a lot of the stuff. Perhaps this was a deliberate conservation strategy; drinking the blood leaves you with an anemic victim that can recover over time and serve as a future food source, while eating the flesh basically relegates your victim to single-serving status; and as we’ve seen, vampires could feed on other species to meet most of their dietary needs. They were much smarter than us, smart enough to figure out the virtues of resource conservation (a concept that baseline humans seem to have a hard time grasping even now).

Читать дальше

![Питер Уоттс - Водоворот. Запальник. Малак [litres]](/books/420290/piter-uotts-vodovorot-zapalnik-malak-litres-thumb.webp)