“Let’s have a few facts first from you,” he countered. “What’s your name and who are you and where do you come from?”

“I am Luchare,” she said. Her voice was rather high-pitched but not nasal. She spoke with pride, not arrogance, just pride. I am who I am, was the unspoken message, that of one who valued herself. Hiero liked her, but kept that fact to himself.

“Very interesting, Luchare,” he said, “and a pretty name, no doubt of it. But what about my other questions? Where is your home? How did you get here?” And what am. I to do about you? was the unspoken one.

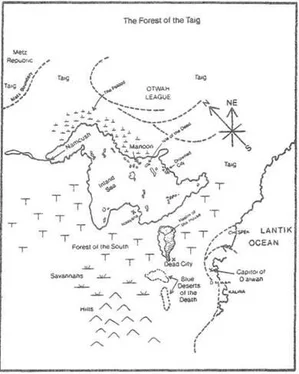

“I ran away from my home,” she said. Her voice, like his, was now flat and emotionless, but she watched him carefully, her eyes bright in the firelight. “My home is far off, far beyond this sea. I think there.” She turned and pointed unerringly to the northwest, in the direction of the Republic.

“I think it unlikely,” the priest said in a dry tone, “because that’s where I come from, and I never heard of anyone like you before. But don’t worry about direction,” he added in a voice he tried to soften; “that’s not important. Tell me about your country. Is it like this? What are your people like? You called those white people who set the birds on you ‘barbarians.’ That’s an odd term for a slave girl to use.”

Their conversation, it may be added, was not at first this smooth and continuous. There were many gaps, fumblings for alternate terms, corrections of pronunciation, and explanation of new words. But both were highly intelligent and quick at adapting. As a result, it went at an increasing rate of progress.

“My people are a mighty and strong one,” she said firmly. “They live in great cities of stone, not dirty huts of hide and leaves. They are great warriors too, and not even the big, homed one could have saved you as he did this afternoon if it had been they you fought.”

Just like a woman, Hiero thought bitterly; give Klootz all the credit. “ AM right,” he said, “your people are great and strong. But what are you doing here, which I gather must be a long way off from wherever you started?”

“First,” she said firmly, “it would be more correct if you told me who you axe, where you are from, and what rank you held in your own country,”

“I am Per Hiero Desteen, Priest, Scholar, and Senior Killmanof the Church Universal. And I fail to see why a bare-rumped chit of a slave girl cares what the rank of the man who has rescued her from an exceedingly nasty death is!” He glared angrily at her, but he might as well have spared himself the effort.

“Your church can’t be all that universal,” she said calmly, “if I haven’t heard of it. Which is not surprising, since it just so happens. Sir Priest, that we happen to have the only true church in my country, and if someone went around looking like you, with silly paint on his face, saying he was a priest, they’d put him in the house for mad people. And furthermore,” she went on in the same flat, lecturing voice, “I was not always a slave girl, as any man with breeding, sense or manners could tell who looked at me!”

Despite his Abbey training in handling people, Hiero found her very annoying. “I beg your pardon, your ladyship,” he rejoined acidly. “You were, I suppose, a princess in your own mighty kingdom, perhaps betrothed to an unwelcome suitor and forced to flee as a result, rather than marry him?”

Luchare stared, open-mouthed at him. “How did you know that? Are you some spy of my father’s or of Efrem’s, sent to bring me back?”

Hiero in turn stared back hard at her, before laughing in a nasty way. “My God, you’ve grabbed up the fantasy of every girl-child who has first heard the legends of the ancient past. Now stop trying to waste my time on this silliness, will you? I want to know about wherever you come from, and I solemnly warn you, I have my own methods of finding out, even if the manners you boast of, plus a little common gratitude, don’t get me the answers I want freely given! Now start talking! Where in the known universe do you come from, and if you really don’t know even that, at least tell me the name of the place, what it’s like, and how you got here!”

The girl looked at him darkly, her eyes narrowed as if in thought. Then, as if she had come to a decision, her face cleared, and she spoke reasonably and in softer tones.

“I am very sorry, Per Hiero—is that right?—I honestly didn’t mean to be rude. I’ve made believe I was someone extra important so long that it’s hard to be normal again. I come from a country which I guess is south of here, only, as you saw just now, I don’t know where south is. I did really live in a city, and the country, especially the wilds, is not what I’m used to. Oh, yes, my country is called D’alwah, and part of it lies on the coast, the salt sea of Lantik, What else did you want to know?”

“Well,” Hiero said more cheerfully, “that’s quite a bit better. I’m not really as nasty as I just sounded. Only remember that I’m fond of straight talk, my girl. Save the fairy tales for the kids from now on and we’ll get along. To start with, how did you get into the fix where I found you?”

As the tiny fire grew dimmer, until it was only an unregarded, winking ember, Luchare spun her tale. Hiero still believed not more than two-thirds of it, but even that was interesting enough to hold him riveted.

Judging from her description, she did indeed come from the far South and East, in fact just about where he himself wanted to go. Which made him listen to every word she dropped with extra special attention.

Her country was a land of wailed cities and giant trees, a tropical forest which reached up to the very sky. It was also a land of constant warfare, of blood and death, of great beasts and warlike men. A church and a priesthood not too unlike that of the Abbeys, so far as he could gather, governed the religion of the people and preached peace and cooperation. But the priests were seemingly incapable of stopping the constant warfare between the various city-states. These states were socially stratified, with castes of nobles, merchants, artisans, and peasants, plus autocratic rulers. There were standing armies, just as large as could be economically maintained without crippling their respective countries through taxation exacted from the peasants to maintain them.

Hiero was frankly incredulous. “Can your people read and write?” he asked. “Have they any of the old books of the past? Do you know of The Death?”

Of course they could read and write, she retorted. Or at least the priesthood and most of the nobles could. The poor were kept too busy to learn, except the few who got into the church. The merchants could do simple, practical arithmetic. What more was needed? As for The Death, everyone knew about it. Were not many of the Lost Cities nearby, and some of the deserts of The Death too? But books from the pre-Death age were forbidden, except perhaps to the priesthood. She herself had never seen one, though she had heard of their existence and also that anyone who found one had to turn it over to the authorities on pain of death.

“Good God!” the Metz exploded. “Your people—and I’m assuming that most of what you’ve told me is the truth—have picked up all the discarded social junk of the dead past at its worst. I knew some of the traders down here had slaves, but I thought they were probably the most primitive people we knew about. The Eastern League at Otwah can’t have heard about you either, because they’re not far behind us. Kingdoms, peasants, internecine warfare, armies, slavery, and general illiteracy! What your D’alwah place needs is a thorough housecleaning!”

Читать дальше