“Yeah, you look it,” said the sergeant.

“I’m speaking Terran, aren’t I?”

“Sure are. A hundred thousand Blowflies can speak it. They think it gives them a certain something.” He waved the cannon again. “The cage, Rogan.”

Rogan took him.

For twelve days he mooched around the prisoner-of-war compound. The dump was very big, very full and swiftly became fuller. Prisoners were fed regularly, guarded constantly and that was all.

Of his fellows behind the wire at least fifty sly-eyed specimens boasted of their confidence in the future when the sheep would be sorted from the goats and justice would be done. The reason, they asserted, was that for a long time they’d been secret leaders of Dirac Angestun Gesept and undoubtedly would be raised to power when Terran conquerors got around to it. Then, they warned, friends would be rewarded as surely as foes would be punished. This bragging ceased only when three of them somehow got strangled in their sleep.

At least a dozen times Mowry seized the chance to attract the attention of a patrolling sentry when no Sirian happened to be nearby. “Psst! My name’s Mowry—I’m a Terran.”

Ten times he received confessions of faith such as, “You look it!” or “Is zat so?”

A lanky character said, “Don’t give me that!”

“It’s true—I swear it!”

“You really are a Terran— hi? ”

“Yar,” said Mowry, forgetting himself.

“Yar to you, too.”

Once he spelled it so there’d be no possibility of misunderstanding. “See here, Buster, I’m a T-E-R-R-A-N.”

To which the sentry replied, “Says Y-O-U” and hefted his gun and continued his patrol.

Came the day when prisoners were paraded in serried ranks, a captain stood on a crate, held a loud-hailer before his mouth and roared all over the camp, “Anyone here named James Mowry?”

Mowry galloped eagerly forward, bow-legged from force of habit. “I am.” He scratched himself, a performance that the captain viewed with unconcealed disfavour. Glowering at him, the captain demanded, “Why the heck haven’t you said so before now? We’ve been searching all Jaimec for you. Let me tell you, Mister, we’ve got better things to do. You struck dumb or something?”

“I—”

“Shut up! Military Intelligence wants you. Follow me.”

So saying, he led the other through heavily guarded gates, along a path toward a prefab hut.

Mowry ventured, “Captain, again and again I tried to tell the sentries that.”

“Prisoners are forbidden to talk to sentries,” the captain snapped.

“But I wasn’t a prisoner.”

“Then what the blazes were you doing in there?” Without waiting for a reply he pushed open the door of the prefab hut and introduced him with, “This is the crummy bum.”

The Intelligence officer glanced up from a wad of papers. “So you’re Mowry, James Mowry?”

“Correct.”

“Well now,” said the officer, “we’ve been primed by beam-radio and we know all about you.”

“Do you really?” responded Mowry, pleased and gratified. He braced himself for the coming citation, the paean of praise, the ceremonial stroking of a hero’s hair.

“Another mug like you was on Artishain, their tenth planet,” the officer went on. “Feller named Kingsley. They say he hasn’t sent a signal for quite a piece. Looks like he’s got himself nabbed. Chances are he’s been stepped on and squashed flat.”

Mowry said suspiciously, “What’s this to me?”

“We’re dropping you in his place. You leave tomorrow.”

“Hi? Tomorrow?”

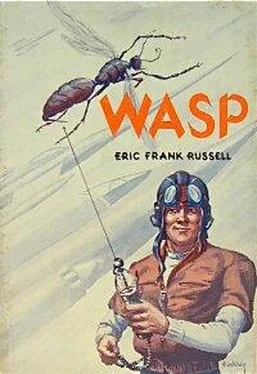

“Sure thing. We want you to become a wasp. Nothing wrong with you, is there?”

“No,” said Mowry, very feebly. “Only my head”