“ I think our mystery customer is after the Titanic. ”

Although most of the human race had seen his handiwork, Donald Craig would never be as famous as his wife. Yet his programming skills had made him equally rich, and their meeting was inevitable, for they had both used supercomputers to solve a problem unique to the last decade of the twentieth century.

In the mid-90s, the movie and TV studios had suddenly realized that they were facing a crisis that no one had ever anticipated, although it should have been obvious years in advance. Many of the classics of the cinema—the capital assets of the enormous entertainment industry—were becoming worthless, because fewer and fewer people could bear to watch them. Millions of viewers would switch off in disgust at a western, a James Bond thriller, a Neil Simon comedy, a courtroom drama, for a reason which would have been inconceivable only a generation before. They showed people smoking.

The AIDS epidemic of the ’90s had been partly responsible for this revolution in human behavior. The twentieth century’s Second Plague was appalling enough, but it killed only a few percent of those who died, equally horribly, from the innumerable diseases triggered by tobacco. Donald’s father had been among them, and there was poetic justice in the fact that his son had made several fortunes by “sanitizing” classic movies so that they could be presented to the new public.

Though some were so wreathed in smoke that they were beyond redemption, in a surprising number of cases skillful computer processing could remove offending cylinders from actors” hands or mouths, and banish ashtrays from tabletops. The techniques that had seamlessly welded real and imaginary worlds in such landmark movies as Who Framed Roger Rabbit had countless other applications—not all of them legal. However, unlike the video blackmailers, Donald Craig could claim to be performing a useful social function.

He had met Edith at a screening of his sanitized Casablanca , and she had at once pointed out how it could have been improved. Although the trade joked that he had married Edith for her algorithms, the match had been a success on both the personal and professional levels. For the first few years, at least…

“…This will be a very simple job,” said Edith Craig when the last credits rolled off the monitor. “There are only four scenes in the whole movie that present problems. And what a joy to work in good old black and white!”

Donald was still silent. The film had shaken him more than he cared to admit, and his cheeks were still moist with tears. What is it, he asked himself, that moves me so much? The fact that this really happened, and that the names of all the hundreds of people he had seen die—even if in a studio reenactment—were still on record? No, it had to be something more than that, because he was not the sort of man who cried easily…

Edith hadn’t noticed. She had called up the first logged sequence on the monitor screen, and was looking thoughtfully at the frozen image.

“Starting with Frame 3751,” she said. “Here we go—man lighting cigar—man on right screen ditto—end on Frame 4432—whole sequence forty-five seconds—what’s the client’s policy on cigars?”

“Okay in case of historical necessity; remember the Churchill retrospective? No way we could pretend he didn’t smoke.”

Edith gave that short laugh, rather like a bark, that Donald now found more and more annoying.

“I’ve never been able to imagine Winston without a cigar—and I must say he seemed to thrive on them. After all, he lived to ninety.”

“He was lucky; look at poor Freud—years of agony before he asked his doctor to kill him. And toward the end, the wound stank so much that even his dog wouldn’t go near him.”

“Then you don’t think a group of 1912 millionaires qualifies under ‘historical necessity’?”

“Not unless it affects the story line—and it doesn’t. So I vote clean it up.”

“Very well—Algorithm Six will do it, with a few subroutines.”

Edith’s fingers danced briefly over the keyboard as she entered the command. She had learned never to challenge her partner’s decisions in these matters; he was still too emotionally involved, though it was now almost twenty years since he had watched his father struggling for one more breath.

“Frame 6093,” said Edith. “Cardsharp fleecing his wealthy victims. Some on the left have cigars, but I don’t think many people would notice.”

“Agreed,” Donald answered, somewhat reluctantly. “If we can cut out that cloud of smoke on the right. Try one pass with the haze algorithm.”

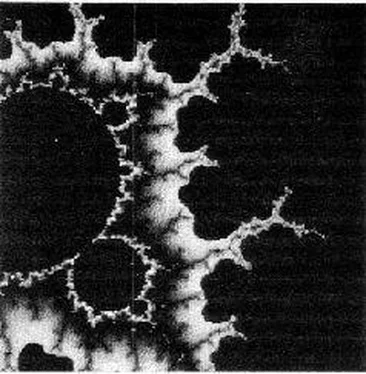

It was strange, he thought, how one thing could lead to another, and another, and another—and finally to a goal which seemed to have no possible connection with the starting point. The apparently intractable problem of eliminating smoke, and restoring hidden pixels in partially obliterated images, had led Edith into the world of Chaos Theory, of discontinuous functions, and trans-Euclidean meta-geometries.

From that she had swiftly moved into fractals, which had dominated the mathematics of the Twentieth Century’s last decade. Donald had begun to worry about the time she now spent exploring weird and wonderful imaginary landscapes, of no practical value—in his opinion—to anyone.

“Right,” Edith continued. “We’ll see how Subroutine 55 handles it. Now Frame 9873—just after they’ve hit… This man’s playing with the pieces of ice on deck—but note those spectators at the left.”

“Not worth bothering about. Next.”

“Frame 21,397. No way we can save this sequence! Not only cigarettes , but those page boys smoking them can’t be more than sixteen or seventeen. Luckily, the scene isn’t important.”

“Well, that’s easy; we’ll just cut it out. Anything else?”

“No—except for the sound track at Frame 52,763—in the lifeboat. Irate lady exclaims: ‘That man over there—he’s smoking a cigarette! I think it’s disgraceful, at a time like this!’ We don’t actually see him, though.”

Donald laughed.

“Nice touch—especially in the circumstances. Leave it in.”

“Agreed. But you realize what this means? The whole job will only take a couple of days—we’ve already made the analog-digital transfer.”

“Yes—we mustn’t make it seem too easy! When does the client want it?”

“For once, not last week. After all, it’s still only 2007. Five years to go before the centennial.”

“That’s what puzzles me,” said Donald thoughtfully. “Why so early?”

“Haven’t you been watching the news, Donald? No one’s come out into the open yet, but people are making long-range plans—and trying to raise money. And they’ve got to do a lot of that —before they can bring up the Titanic. ”

“I’ve never taken those reports seriously. After all, she’s badly smashed up—and in two pieces.”

“They say that will make it easier. And you can solve any engineering problem—if you throw enough cash at it.”

Donald was silent. He had scarcely heard Edith’s words, for one of the scenes he had just watched had suddenly replayed itself in his memory. It was as if he was watching it again on the screen; and now he knew why he had wept in the darkness.

“Goodbye, my dear son,” the aristocratic young Englishman had said, as the sleeping boy who would never see his father again was passed into the lifeboat.

And yet, before he had died in the icy Atlantic waters, that man had known and loved a son—and Donald Craig envied him. Even before they had started to drift apart, Edith had been implacable. She had given him a daughter; but Ada Craig would never have a brother.

Читать дальше