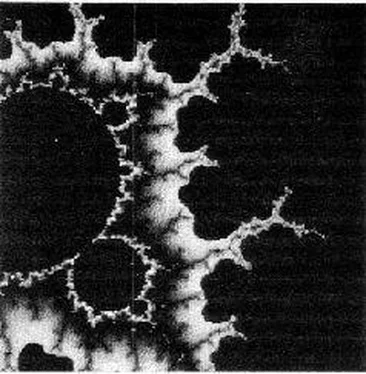

The stunning beauty of the images it generates means that its appeal is both emotional and universal. Invariably these images bring gasps of astonishment from those who have never encountered them before; we have seen people almost hypnotized by the computer-produced films that explore its—quite literally—infinite ramifications.

Thus it is hardly surprising that within a decade of Benoit Mandelbrot’s 1980 discovery it began to have an impact on the visual arts and crafts, such as the designs of fabrics, carpets, wallpaper, and even jewelry. And, of course, the Hollywood dream factories were soon using it (and its relatives) twenty-four hours a day…

The psychological reasons for this appeal are still a mystery, and may always remain so; perhaps there is some structure, if one can use that term, in the human mind that resonates to the patterns in the M-Set. Carl Jung would have been surprised—and delighted—to know that thirty years after his death, the computer revolution whose beginnings he just lived to see would give new impetus to his theory of archetypes and his belief in the existence of a “collective unconscious.” Many patterns in the M-Set are strongly reminiscent of Islamic art; perhaps the best example is the familiar comma-shaped “Paisley” design. But there are other shapes that remind one of organic structures—tentacles, compound insect eyes, armies of seahorses, elephant trunks… then, abruptly, they become transformed into the crystals and snowflakes of a world before any life began.

Yet perhaps the most astonishing feature of the M-Set is its basic simplicity. Unlike almost everything else in modern mathematics, any schoolchild can understand how it is produced. Its generation involves nothing more advanced than addition and multiplication; it does not even require subtraction or division, much less any higher functions…

In principle—though not in practice!—it could have been discovered as soon as men learned to count. But even if they never grew tired, and never made a mistake, all the human beings who have ever existed would not have sufficed to do the elementary arithmetic required to produce an M-Set of quite modest magnification…

(From “The Psychodynamics of the M-Set,” by Edith and Donald Craig, in Essays Presented to Professor Benoit Mandelbrot on his 80th Birthday : MIT Press, 2004.)

“Are we paying for the dog, or the pedigree?” Donald Craig had asked in mock indignation when the impressive sheet of parchment had arrived. “She’s even got a coat of arms, for heaven’s sake!”

It had been love at first sight between Lady Fiona McDonald of Glen Abercrombie—a fluffy half-kilogram of Cairn terrier—and the nine-year-old girl. To the surprise and disappointment of the neighbors, Ada had shown no interest in ponies. “Nasty, smelly things,” she told Patrick O’Brian, the head gardener, “with a bite at one end and a kick at the other.” The old man had been shocked at so unnatural a reaction from a young lady, especially one who was half Irish at that.

Nor was he altogether happy with some of the new owners” projects for the estate on which his family had worked for five generations. Of course, it was wonderful to have real money flowing into Conroy Castle again, after decades of poverty—but converting the stables into computer rooms! It was enough to drive a man to drink, if he wasn’t there already.

Patrick had managed to derail some of the Craigs” more eccentric ideas by a policy of constructive sabotage, but they—or rather Miz Edith—had been adamant about the remodeling of the lake. After it had been dredged and some hundreds of tons of water hyacinth removed, she had presented Patrick with an extraordinary map.

“ This is what I want the lake to look like,” she said, in a tone that Patrick had now come to recognize all too well.

“What’s it supposed to be?” he asked, with obvious distaste. “Some kind of bug?”

“You could call it that,” Donald had answered, in his don’t-blame-me-it’s-all-Edith’s-idea voice. “The Mandelbug. Get Ada to explain it to you someday.”

A few months earlier, O’Brian would have resented that remark as patronizing, but now he knew better. Ada was a strange child, but she was some kind of genius. Patrick sensed that both her brilliant parents regarded her as much with awe as with admiration. And he liked Donald considerably more than Edith; for an Englishman, he wasn’t too bad.

“The lake’s no problem. But moving all those grown cypress trees—I was only a boy when they were planted! It may kill them. I’ll have to talk it over with the Forestry Department in Dublin.”

“How long will it take?” asked Edith, totally ignoring his objections.

“Do you want it quick, cheap, or good? I can give you any two.”

This was now an old joke between Patrick and Donald, and the answer was the one they both expected.

“Fairly quick—and very good. The mathematician who discovered this is in his eighties, and we’d like him to see it as soon as possible.”

“Nothing I’d be proud of discovering.”

Donald laughed. “This is only a crude first approximation. Wait until Ada shows you the real thing on the computer; you’ll be surprised.”

I very much doubt it, thought Patrick.

The shrewd old Irishman was not often wrong. This was one of the rare occasions.

Jason Bradley and Roy Emerson had a good deal in common, thought Rupert Parkinson. They were both members of an endangered, if not dying, species—the self-made American entrepreneur who had created a new industry or become the leader of an old one. He admired, but did not envy them; he was quite content, as he often put it, to have been “born in the business.”

His choice of the Kipling Suite at Brown’s for this meeting had been quite deliberate, though he had no idea how much, or how little, his guests knew about the writer. In any event, both Emerson and Bradley seemed impressed by the ambience of the room, with the historic photographs around the wall, and the very desk on which the great man had once worked.

“I never cared much for T. S. Eliot,” began Parkinson, “until I came across his Choice of Kipling’s Verse. I remember telling my Eng. Lit. tutor that a poet who liked Kipling couldn’t be all bad. He wasn’t amused.”

“I’m afraid,” said Bradley, “I’ve never read much poetry. Only thing of Kipling’s I know is ‘If—’ ”

“Pity: he’s just the man for you—the poet of the sea, and of engineering. You really must read ‘McAndrew’s Hymn’; even though its technology’s a hundred years obsolete, no one’s ever matched its tribute to machines. And he wrote a poem about the deep sea cables that you’ll appreciate. It goes:

“The wrecks dissolve above us; their dust drops down from afar—

Down to the dark, to the utter dark, where the blind white sea-snakes are.

There is no sound, no echo of sound, in the deserts of the deep,

Or the great grey level plains of ooze where the shell-burred cables creep.”

“I like it,” said Bradley. “But he was wrong about ‘no echo of sound.’ The sea’s a very noisy place—if you have the right listening gear.”

“Well, he could hardly have known that , back in the nineteenth century. He’d have been absolutely fascinated by our project—especially as he wrote a novel about the Grand Banks.”

“He did?” both Emerson and Bradley exclaimed simultaneously.

“Not a very good one—nowhere near Kim —but what is? Captains Courageous is about the Newfoundland fishermen and their hard lives; Hemingway did a much better job, half a century later and twenty degrees further south…”

Читать дальше