“Was that five ‘times tens’?” I said. “Yes, that’s a million.”

“Sixty … five … million … years,” said the thing. It paused, then hawked blood onto the ground again. “What you say difficult to comprehend.”

“Nevertheless, it’s true,” I said. For some reason, I took a perverse pleasure in impressing the thing. “I realize sixty-odd million years is an impossibly long time to conceive of.”

“We conceive it; we remember a time twice as long ago,” the troodon said.

“My God. You remember, what, a hundred and thirty million years ago?”

“Intriguing that you own a god,” said Diamond-snout.

I shook my head. “You’ve got a history of a hundred and thirty million years?” Dating back from here at the end of the Cretaceous, that would be around the Triassic-Jurassic boundary.

“History?” said the troodon.

“Continuous written record,” said Klicks. He paused for a moment, I guess realizing that the jelly creatures couldn’t possibly have writing as we know it, since they didn’t have hands. “Or a continuous record of the past in some other form.”

“No,” said the troodon, “we do not that have.”

“But you just said you remembered a time a hundred and thirty million years ago,” said Klicks, frustration in his voice.

“We do—”

“So how can you—”

“But we not aware that time travel is possible,” said Diamond-snout, overtop of Klicks. “Last night, that black and white disk that crashed into the ground. That was your vehicle for time displacement?”

“The Sternberger , yes,” said Klicks. “Its technical name is a Huang temporal phase-shift habitat module, but the press just calls it a time machine.”

“A time machine?” The reptilian head bobbed. “That phrase appeals. Tell how it works.”

Klicks appeared irritated. “Look,” he said. “We know nothing about you. You’ve crawled around in our heads. What the hell are you?”

For the first time, I noticed the way the troodon blinked, an odd gesture in which it closed its left eye, opened it, then briefly closed its right. “We entered you only to absorb your language,” Diamond-snout said. “Did no harm, yess?”

“Well—”

“We could enter you again to absorb additional information. But time-consuming process. Clumsy. Language center obvious in brain structure. Much mass devoted to it. Specific memories much harder to faucet. Faucet? No, to tap. Easier you tell us.”

“But we could communicate better if we knew more about you,” I said. “Surely you can see that a common set of references would make it simpler.”

“Yess. See that and raise you—No, just see that. Common reference points. Links. Very well. Ask questions.”

“All right, then,” I said. “Who are you?”

“I am me,” the reptile said.

“Great,” muttered Klicks.

“Unsatisfactory response?” asked the theropod. “I am this one. No name. Name not link.”

“You’re a single entity,” I said, “but you don’t have a name of your own. Is that it?”

“It is that.”

“How do you tell yourself from others of your own kind?” I asked.

“Others?”

“You know: different individuals. One of you is inside this troodon; another is inside that one. How do you distinguish yourselves?”

“I here. Other is there. Easy as 3.1415.”

Klicks hooted.

“What are you?” I asked, annoyed at Klicks.

“No link.”

“You are an invertebrate.”

“Invertebrate: animal without a backbone, yess?”

“Yes. What are your relatives?”

“Time and space.”

“No, no. I—Damn. I want to know what you are, what you evolved from. You’re unlike any form of life I’ve seen before.”

“As are you.”

I shook my head. “I’m not too dissimilar from the dinosaur you are now inhabiting.”

“Dinosaur is efficient creature. Strong. Keen senses. Yours are dull by comparison.”

“Yes,” I said, irritated. For years, I’d explained to people that dinosaurs weren’t the sluggish, stupid creatures so often portrayed in cartoons, but somehow I didn’t enjoy hearing the same sentiments expressed by a reptilian mouth. “But we are more similar than different. Each of us is bipedal—that means we each have two legs—”

“Bipedal links.”

“And we each have two arms, two eyes, two nostrils. Our left sides are nearly perfect mirror images of our right sides—”

“Bisexual symmetry.”

“Bilateral symmetry,” I corrected. “Clearly, the dinosaur and I are related—share a common ancestor. My kind did evolve from ancient reptiles, but there are other creatures about, tiny mammals, that are even more closely related to us. But you—I’ve studied the history of life since it began. I don’t know of anything similar to you.”

“Its body is completely soft,” said Klicks. “Creatures like that might go undetected in the fossil record.”

I turned to him. “But intelligent life arising millions of years before the first human? It’s incredible. It’s almost as if—”

I’d like to claim that I was about to state the correct conclusion, that at that instant I had pieced together the puzzle and had realized what was going on. But my next words were drowned out by a great roaring clap, like thunder, followed by several bellowing dinosaur calls and the cries of flying things startled into flight. I recognized the noise, for my home was due south of Pearson International Airport and, despite the complaints from me and my neighbors, it had become part of the background of our day-to-day lives ever since Transport Canada had approved inland supersonic flights of the Orient Express jetliners. High overhead, three tawny spheres moving at perhaps Mach 2 or 3 streaked across the sky. At the least, they were aircraft, but I knew in an instant that they were much more than that.

Spaceships.

“You under a misapprehension operate,” said Diamond-snout once the sky had stopped rumbling. “We are not from this planet.”

Klicks was flabbergasted, which pleased me no end. “Then where?” I said.

“From—home world. Name I not find in your memories. It’s—”

“Is it in this solar system?” I asked.

“Yess.”

“Mercury?”

“Quicksilver? No.”

“Venus?”

“No.”

“Not Earth. Mars?”

“Mars—ah, Mars! Fourth from sun. Yess. Mars is home.”

“Martians!” said Klicks. “Actual fucking Martians. Who’d believe it?”

Diamond-snout fixed Klicks with a steady gaze. “I would,” it said, absolutely deadpan.

I can be expected to look for truth but not to find it.

—Denis Diderot, French philosopher (1713-1784)

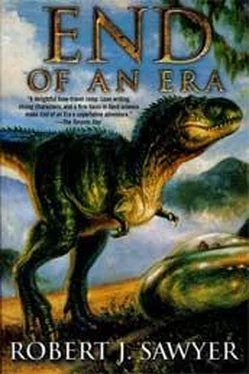

The traveler’s diary—the one that purported to tell the story of a trip back to the end of the Mesozoic Era—had to be a fake, of course. It had to be. Oh, it superficially resembled my writing style. In fact, whoever had put it together had obviously read my book Dragons of the North: The Dinosaurs of Canada . In preparing the manuscript for that book, I got sick of all the italics. See, Linnaeus established that biological naming would be in Latin, and non-English words are usually italicized in modern typesetting. Plus, Linnaeus said the genus part of the name should always be capitalized: Tyrannosaurus rex. Since there are no common English names for individual types of dinosaurs, popular books on the subject have slavishly followed this convention so that almost every tenth word is italicized or capitalized, bullying the reader’s eye.

I’d taken some flak from my colleagues for it, but in Dragons of the North I chucked out that convention. The first time I mentioned some Mesozoic critter, I’d use the Linnaean standard, but thereafter I’d treated the name as if it were a common English term, just like “cat” or “dog,” uncapitalized and unitalicized. Well, whoever had cobbled together this bogus diary had copied at least that much of my style.

Читать дальше