Tobias S. Buckell

ARCTIC RISING

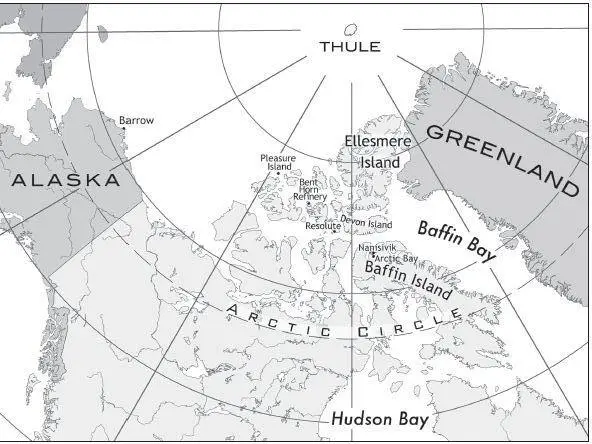

Centuries ago, the fifty-mile-wide mouth of the Lancaster Sound imprisoned ships in its icy bite. But today, the choppy polar waters between Baffin Island to the south of the sound, and Devon Island on the north, twinkled in the perpetual sunlight of the Arctic’s summer months, and tons of merchant traffic constantly sailed through the once impossible-to-pass Northwest Passage over the top of Canada.

A thousand feet over the frigid, but no longer freezing and ice-choked waters, the seventy-five-meter-long United Nations Polar Guard airship Plover hung in a slow-moving air current. The turboprop engines growled to life as the fat, cigar-shaped vehicle adjusted course, then fell silent.

Inside the cabin of the airship, Anika Duncan checked her readings, then leaned over the matte-screened displays in the cockpit to look out the front windows.

The airship’s cabin had once held twelve passengers, but was now retrofitted with a bunk, a small kitchen area, supply closets, and a cramped navigation station. Tourists had once sat in the cabin underneath the giant gasbag as the airship glided over New York’s tallest buildings. After that tour of duty, the United Nations Polar Guard purchased it well used and very cheap.

Airships didn’t use much fuel. They could put observers into the air to monitor ship traffic for days at a time, wafting from position to position with air currents.

It saved money. And Anika knew the UNPG was always struggling with a lean budget. It showed on her paycheck, too.

“Which ship should we take a closer look at, Tom?” Anika asked.

She’d unzipped her bright red cold-sea survival suit and rolled it down to her waist, as it was too hot for her to wear fully zipped up as regulations required. She had her frizzy hair pulled back in a bouncy ponytail: a week without relaxant meant it had a mind of its own right now. She’d consider letting it turn to dreads if she could, but the UNPG didn’t approve. And yet, she thought to herself, they expected her to sit up in the air for a week without a real shower.

Someone once told her to just shave it. But she liked her hair. Why hide it? As long as it was tied up, regs said she could have longer hair.

Now Thomas Hutton, her copilot, was all about the regs and then some. He had his blond hair millimeter short. Shorter than required. But even he wore his survival suit halfsies.

It was one of those balancing acts: if they kept it cold enough in the airship’s cabin to wear the suits zipped up, using the tiny, cramped toilet was torture.

Particularly, Tom said, for the guys.

“Tom?” she prompted.

“Yeah, I’m looking, I’m looking.” He walked back from the nav station, the top half of his suit floppily smacking along behind him as he peered down through the windows along the way.

Four ships were funneling their way into the Lancaster Sound from the east, where Greenland lurked beneath the curve of the horizon. The ships looked like bath toys from up at this height. Three of the ships had large wing-shaped parafoils hanging in the sky overhead. The parafoils, connected to the ships by cables, reached up to where the strong winds were blowing to drag the ships through the water.

“I want to take a closer look at that oil burner,” Tom finally announced.

“You are getting predictable,” Anika said as he slid into the copilot’s seat. Though one of the things she liked about Tom was his easy predictability. Her own life had been chaotic enough before coming so far north. It was a different pace up here. A different chapter of her life. And she liked it. “It is supposed to be a random check?”

He pointed at the black plume of smoke trailing from the stacks of the fourth ship in the distance. “That one sticks out like a sore thumb. Hard to say no to.”

Anika tapped the scratched and well-worn touch screens around her. She pulled up video from one of the telephoto-lens cameras mounted on the prow of the cabin and zoomed in on the fourth ship.

Thirty meters long with a bulbous-prowed hull, flaking rust, and colored industrial gray, the ship was pushing fifteen knots in its rush to pass through the sound.

“They seem to be in a hurry.”

Tom glanced over. “Fifteen knots? She hits a berg at that speed she’ll Titanic herself quickly enough.”

The Arctic still had an island of ice floating around the actual Pole. It was kept alive by a fusion of conservationists, tourism, and the creation of a semi-country and series of ports that sprang up called Thule. They’d used refrigerator cables down off platforms to keep the ice congealed around themselves despite the warmed-up modern Arctic, a trick learned from old polar oil riggers who’d done that to create temporary ice islands back at the turn of the century.

It was an old trick that didn’t really work anywhere else but near the Pole now. But even the carefully artificial polar ice island that was Thule still calved chunks, some of which would get as far south as Lancaster.

Hit one at the speed this ship was going, they’d sink easily enough.

“Shall we get closer to him and sniff him over?” Anika asked. “Remind him to slow down.”

Tom grinned. “Yeah, their credentials should come through shortly. The scatter camera’s up. Let’s see if this ship’s radioactive.”

* * *

The neutron scatter camera, mounted on a gimbaled platform right next to the telephoto cameras, hunted for radioactive signatures. Port authorities had been using them to hunt for potential terrorist bombs for decades. But what they found, over time, was a secondary use for the scatter cameras: catching nuclear waste dumpers.

At the turn of the century, after the tsunami that washed over East Asia, UN monitors found themselves contacted by East African countries about industrial pollutants washing up on the beaches. People had been falling sick after approaching large, well-insulated drums washed up from deep in the ocean. People had also been showing statistically high rates of cancer near coastlines throughout countries where standing navies and coast guards just didn’t exist.

Toxic waste, including spent nuclear fuel, was clearly getting dumped off non-monitored coasts by commercial shipping.

The gig started when a shady company got the lowest bid for safely storing fuel or industrial waste. Ostensibly, they were transporting it out of country to another location.

In reality, once offshore of some struggling African country with no navy, they’d dump it.

Even so-called “first world” countries weren’t immune. A statistical study of waste-transporting merchant ships thirty years ago showed a higher number of merchant ships “sinking” in the deeper Mediterranean.

Charter an old leaker, stuff it with barrels full of whatever the host country and its businesses didn’t want. Take the big payout, head out to sea, and then experience difficulties. Instant massive profit.

The African and Mediterranean dumping had faded with the EU and East African naval buildups and public outrage. More dumping was going on off Arabic coasts these days. The post oil-boom nations were too busy trying to destroy each other for what little black gold was left to have the capability to worry about what was going on off their coastlines.

Читать дальше