“Jeee-sus.”

“Welcome to the real world.”

“So Aarons is going for J-11. What about probing Jupiter’s atmosphere near the poles?”

Zak shrugged. “Most of the bio boys say that stuff you found comes from deep down—too deep for us to reach.”

“Ummm. Hey, you said the crew’s been selected?”

“Yeah. Aarons said—oh, I get it.” He grinned. “You want to go.”

“Sure. Wouldn’t you?”

“Well, yeah, but…” He scowled. “My stock’s not so high right now, anyway.”

“Huh? Why not?”

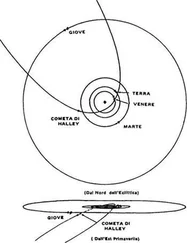

Zak smiled wryly. “It’s because of you, basically. You remember how Kadin got all fired up about those meteor swarm orbits?”

“Yeah.”

“He assigned a couple of numerical specialists to comb back through the deep-memory storage and get all the records we had. That’ll give us a history of the activity, Kadin thought. Maybe the early automated satellites—the post-Voyager craft—had picked up some odd stuff. So these numerical types went in and got everything out of storage, even the post-Voyager stuff, and started going through it, and…”

He paused significantly. A suspicion blossomed in my mind. “And you… Rebecca and Isaac…”

Zak nodded sourly.

“You said you had a foolproof place to store ’em.” I couldn’t help laughing.

“No need to cackle with glee,” Zak muttered.

“And it had your ident code, right? So they knew right away whose it was.”

“I never thought anybody’d go back into that old crap.”

“Who nailed you?”

“Aarons called me in. Christ, I didn’t think it would be that big a thing. I mean, with all that’s going on—”

“What’d he say?”

“He gave me a long look and said something about improper use of facilities, and how I’d have a watchdog program on all my work from now on.”

“You got off easy.”

“Yeah. I guess. But I’m not any fair-haired boy, I can tell that. The comp center people keep laughing behind my back.”

“Laughing?”

“Yeah. They seem to find some of what Rebecca and Isaac did, well, amusing.”

“Ummm. Not, uh, exciting?”

“I guess not.” Zak looked sour. I could tell he was more bothered by the laughter than the watchdog program. I mean, to have your sexual fantasies taken as inept comedy…

I suppressed a smile and slapped him on the back. “Come on and have some breakfast.”

“Don’t you want to see the crew manifest for Sagan? ”

“Oh yeah.” Zak handed me a disposable printout. I scanned the names. Military people, mostly.

“Going to be some trip, all right,” Zak mused.

“Yeah.” Suddenly I wanted to go. To trace the swarms to their origin.

Zak could read my face. “Come on,” he said. “Forget it. You may be the accidental savior, but you’re still a kid.”

We had breakfast. Zak didn’t mind wolfing down a second; it helped console him. I was kind of quiet, thinking about J-11. Zak scooped up the tofu eggs and grumbled over his bad luck.

“You know,” he said at last, “maybe I should’ve stuck to real life. Forget Rebecca and the business angle.”

“Meaning what?”

“I should’ve put my effort into finding Lady X.”

“You’ll never learn, Zak.”

Zak had a shift to work, so I wandered around for a while at loose ends. I wound up in the inner levels, near Hydroponics, and decided to put in some of my chore time there. Everybody has to do twenty hours a month of simple labor—recycling, cleaning filters, hauling stuff, anything that’s so tedious that nobody wants to do it full time. Hydroponics work is mandatory for everybody, though, both because we have to maximize the food cultivated in the space allowed, and because it’s psychologically good for you.

I checked in, got a work suit and found Mom. She was titrating a new fertilizing solution, checking its chemical balance. I left her to that and worked for a while putting patches on the duro tubing. I had to crawl through the close-packed, leafy tangle. In low G the plants grow two, maybe three times Earth norm. Tomatoes look like watermelons, and watermelons—well, you’ve got to see one to believe it. I went by the huge vat that holds Turkey Lurkey and peeked in. The big sweaty pale mass was perking right along, growing so fast you could almost see it swelling up. All the Can’s meat comes from Turkey Lurkey. The chem wizards alter its taste with minute trace impurities, to make it seem like beef or fish or chicken. A lot of people Earthside thought Turkey Lurkey was here because eating live animals was wrong. Maybe that’s a superior philosophical position, but the plain fact is that Turkey Lurkey is the only efficient way we could have any meat at all. There wasn’t room for beef cattle or even chickens. Maybe the ethical issue was wrong anyway, because who was to say Turkey Lurkey wasn’t conscious? Sure, it had a nervous system that made a nineteenth century telegraph line look like an IBM 9000, but what did that mean? Some neurophilosophers Earthside now think that consciousness may be a continuum, right down to plants. Who’s to say? The plants aren’t talking.

On our break I talked to Mom. As soon as I could, I brushed aside the talk about finding the stuff in the satellite. I mean, for some reason, praise from your own mother seems kind of obligatory. She’d say good things no matter what. And anyway, I wasn’t interested in the past. I wanted in on the J-11 mission.

Mom didn’t have any advice about that one, other than to suggest that I go see Commander Aarons about it. I knew that wouldn’t work. So I talked about other things, and eventually we got around to the things Zak had said to me while I was out there, and about Earthside and my memories and all. I told Mom how I felt. It wasn’t easy.

“Yes, I remember Dr. Matonin mentioning that to me,” Mom said.

“Huh? When?”

“Oh, years ago.”

“How’d she know?”

“Why, they have a profile on everyone.”

“Why’d she never say anything to me about it?”

“I suppose she thought it wouldn’t do any good.”

“She told you. ”

“Only to make me more aware of the problem. We weren’t gossiping behind your back, Matt.”

“What was the good Doctor’s therapy?” I asked dryly.

Mom smiled. “No therapy. There’s a limit to what anyone else can do about these things, Matt.”

“Right,” I muttered gruffly. “Damned right.”

Something in that conversation crystallized my thoughts. I felt a slow, sullen anger building up inside me. I went over to the storage shed and threw bags of fertilizer onto the slideways. Hefting them up and dumping them down gave my muscles a chance to do my thinking for me. Long ago I’d learned that when I felt this way, a workout was the best solution. Fertilizer bags can’t fight back.

And as I sweated and grunted it all started to make sense. Doctor Matonin and her mother-henning. Those dumb Socials. Yuri’s father, making his son look like a fool by acting out some antique dream of Earthside. They were all putting blinders on us, shaping us with their dimly remembered ideas about growing up.

I thought about Jenny. The only time we had really said anything worth a damn to each other was on Roadhog. Outside the Can. On our own. Away from all the eyes and ever-ready advice. Away from the rules and guidelines, and the whole goddam suffocating adult world.

I had learned something out there in the long, black hours on Roadhog. I would have seen it eventually, I knew, if I’d just kept on with the orbital missions. My crazy run to get the Faraday cup had just speeded up the process. Getting outside the Can gave you a perspective. It was a big help to look back on your whole life and see it stuffed into a tin box, literally see it for the tight little world it was. Because otherwise, you’d buy the official Can point of view. You’d go along. And you’d never really grow up. You’d turn into a Zak, wiseassing your way through life. Or a Yuri, crippled by a blockhead parent. That was the danger of compression, of packing people so close together they had to get along. In those circumstances, everybody had to back down, live life according to the consensus rules.

Читать дальше