A hand took my elbow roughly and guided me through the crowd. I winked at Jenny, hoping I looked self-confident.

There were two medical attendants with me. They hustled me into an elevator and we zipped inward five levels. I was in a daze. A doctor in a white coat poked at me, took a blood sample, urinanalysis, skin sections—and then ordered me into a ’fresher.

I got a new set of standard ship work clothes when I came out, and a light supper. My time sense was all fouled up; it was early morning, ship’s time, but my stomach thought it was lunch. And I felt like I was a million years old.

After that they left me alone.

Finally someone stuck his head in a door and motioned me into the next room. The doctor was in there, reading a chart.

“Young man,” he said slowly, “you have given me and your parents and a lot of other people a great deal of trouble. That was an extremely foolish gesture to make. These past few days have been hard on all of us, but such heroics are not to be excused.”

He looked at me sternly. “I imagine the Commander will have more to say to you. I hope he disciplines you well. By freak chance, you seem to have avoided getting a serious dosage of radiation. Your blood count is nearly normal. I expect it will reach equilibrium again within a few hours.”

“I’m okay?”

“That is what I said. Your—”

There was a knock at the door. It opened and a bridge officer looked in. “Finished. Doctor?”

“Nearly.” He turned to me. “I want you to know that you came very close to killing yourself, young man. The background level out there is rising rapidly; it very nearly boiled you alive. Commander Aarons will make an example of you—”

“No doubt.” I got up. The Doctor pressed his lips together into a thin line, then nodded reluctantly to the officer. We left.

“What now?” I said in the tube outside. “The Commander’s office?”

“Nope. Mr. Jablons’.”

“Why?”

They don’t let me in on their secrets. The Commander is there now. He sent me for you. If it was up to me I’d have you thrashed, kid.”

I didn’t say anything more until we reached the electronics lab. There weren’t any more convenient excuses. No dodges, no explanations. I had pulled off a dumb stunt and saved my neck only by smashing up Roadhog.

I slumped as I walked beside the bridge officer, my shoulders sagging forward. My conversation with Zak drifted through my head. Self-knowledge is usually bad news. Yeah. I thought back over what had been happening to me, the way one moment I’d act reasonably mature, and then the next minute I’d come on like some twelve-year-old. I hadn’t dealt with Yuri. I hadn’t straightened out my feelings about women, I hadn’t even been able to take looking like a failure in Mr. Jablons’ eyes…

Fuzzy thoughts floated by. The corridor seemed to ripple as I followed the bridge officer. I felt like some Earthside dope-o on mindwipe.

I took a deep breath and my head cleared a little. The bridge officer scowled at me. I tried to give him a smile with some bravado in it. It didn’t work. We reached the electronics lab.

The Commander himself opened the door and waved the bridge officer away. He didn’t look angry. In fact, he hardly saw me as I came in and closed the door. He was gazing off into space, thinking.

Dad and Mr. Jablons were sitting at one of the work benches. Dr. Kadin was working at a high-vacuum tank in the middle of the room. His hands were inserted in the waldoes and he was moving something inside the tank.

Dad looked up when I came in. “Ah, there you are, Mr. Lucky.”

“Huh?”

“Look in the tank.”

I walked over and looked through the glass. The Faraday cup was inside. Some of the sticky dust had been taken out with the waldo arms and scattered over a series of pyrex plates. The plates were spotted with green and blue chemicals and one of the plates was fixed under a viewing microscope.

“That contaminant you found inside the cup wasn’t dust, Matt,” my father said. “It is a colony of—well, something like spores. They are still active, as far as we can tell.”

Dr. Kadin turned and looked at me. “Quite so. It would seem, young Mr. Bohles, that you have discovered life on Jupiter.”

Suddenly everybody in the room was smiling: Mr. Jablons laughed. “When they write this up in the history books, they’ll have to record that blank look of yours, Matt.”

I realized that my jaw was hanging open and quickly shut it. “Wha—How?”

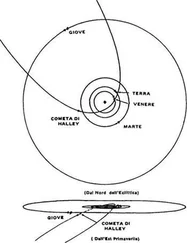

“How did it get there?” Dr. Kadin. said. “That is a puzzle. I imagine these spores—if that is indeed what they are—somehow traveled up through the Jovian atmosphere by riding along—‘piggyback’ I believe you say—on the electric fields produced by the turbulent storms.”

Mr. Jablons slapped his knee. “I knew it would happen! Half an hour ago we didn’t know if that dust was alive, and already a theory has raised its head.”

Dr. Kadin ignored him. “You might have a look at them through the microscope,” he said. “There are very interesting aspects.”

I bent my head over the eyepiece of the microscope. Against a yellow smear I could see three brownish lumps. They looked like barbells with a maze of squiggly blue lines inside them. They weren’t moving; the smear had killed them.

“Note the elongated structure,” Dr. Kadin said at my ear. “Most unusual for such a small cell. Of course, these do not appear to be at all similar to Earthly cells in other particulars, so perhaps such a difference is not surprising.”

“I don’t get you,” Dad said.

“I believe these organisms may use that shape to cause a separation of electrical charge in their bodies. Somehow, deep in the atmosphere, they shed charge. Then, when a storm blows them to the top of the cloud layer, they become attached to the complicated electrical field lines near the north pole.”

“That’s what brought them out to Satellite Fourteen?” I asked.

“I think so. It is the only mechanism I can imagine that would work.”

“Why did the Faraday cup malfunction?” Commander Aarons asked. It was the first thing be had said since I arrived.

“Well, consider. When an electron strikes the cup it passes through the positive grid and strikes the negative plate. From there it passes down a wire and charges a capacitor. These spores—or whatever—are also charged; they will be trapped in the same manner. But they do not pass down the wire; only between grid and plate, eventually filling it up. They still retained some of their charge, though, and when they piled up high enough to connect the grid and the plate they shorted out the circuit.” Dr. Kadin looked around, as if for approval.

“That could be why the Faraday cup failed, all right,” Mr. Jablons said.

“I couldn’t tell much from the microscope,” I said. “Dr. Kadin, what are those cells like?”

“They seem to be carbon-based. They are not carbon dioxide absorbers, however, like terrestrial plants; perhaps they breathe methane. They have a thick cell wall and some structures I could not identify. Calling them spores is only a guess, really.”

Commander Aarons shook his head. “You are certain these things couldn’t have been left there by accident—just be something from the Can that was on the Bohles boy’s gloves when he took it out?”

“No. They are like nothing I have ever seen.”

“But what are they doing out there?” Dad said. “Why should organisms evolve that can be thrown clear above the atmosphere? If that bunch hadn’t been trapped in Satellite Fourteen they could have gone all the way to the south pole, riding along on the magnetic fields.”

Читать дальше