The site for the transmitter had been carefully chosen, high up, surrounded by forest, backed by mountains, an easy place to defend against ground attack. They had cleared the area immediately around the installation, but the trees were not far away. We lived in prefabricated buildings that let in the rain. Everything felt damp to the touch. The floors were concrete, always covered in mud. Everywhere we walked became a morass. Everyone grumbled about the discomfort and the poor quality of the food.

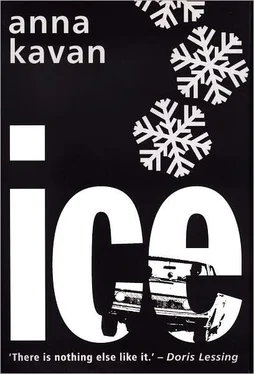

Something had gone wrong with the weather. It should have been hot, dry, sunny; instead it rained all the time, there was a dank chill in the air. Thick white mists lay entangled in the tops of the forest trees; the sky was a perpetually steaming cauldron of cloud. The forest creatures were disturbed, and departed from their usual habits. The big cats lost their fear of man, came up to the buildings, prowled round the transmitter; strange unwieldy birds flopped overhead. I got the impression that birds and animals were seeking us out for protection against the unknown danger we had unloosed. The abnormalities in their behaviour seemed ominous.

To pass the time and for want of something better to do, I organized the work on the transmitter. It was not far from completion, but the workers had grown discouraged and apathetic. I assembled them and spoke of the future. The belligerents would listen and be impressed by the impartial accuracy of our reports. The soundness of our arguments would convince them. Peace would be restored. Danger of universal conflict averted. This was to be the final reward of their labours. In the meantime, I divided them into teams, arranged competitions, awarded prizes to those who worked best. Soon we were ready to start broadcasting. I recorded events on both sides with equal respect for truth, put out programmes on world peace, urged an immediate cease fire. The minister wrote, congratulating me on my work.

I could not make up my mind whether to cross the frontier or to stay where I was. I did not think the girl could be alive in the demolished town. If she had been killed there it was pointless to go. If she was safe somewhere else there was no point in going either. Considerable personal risk was involved. Although a non-combatant, I was liable to be shot as a spy, or imprisoned indefinitely.

But I was becoming tired of the work here now that everything was running smoothly. I was tired of trying to keep dry in the perpetual rain, tired of waiting to be overtaken by ice. Day by day the ice was creeping over the curve of the earth, unimpeded by seas or mountains. Without haste or pause, it was steadily moving nearer, entering and flattening cities, filling craters from which boiling lava had poured. There was no way of stopping the icy giant battalions, marching in relentless order across the world, crushing, obliterating, destroying everything in their path.

I made up my mind to go. Without telling anyone, in the drenching rain, I drove to the blocked pass, and from there found my way over the tree covered mountains on foot. I had only a pocket compass to guide me. It took me several hours of climbing and struggling through wet vegetation to reach the frontier station, where I was detained by the guard.

I asked to be taken to the warden. He had lately moved his headquarters to a different town. An armoured car drove me there; two soldiers with submachine guns came too, ‘for my protection’. It was still raining. We crashed through the downpour under heavy black clouds which shut out the last of the day. Darkness was falling as we entered the town. The headlights showed the familiar scene of havoc, rubble, ruins, blank spaces, all glistening in rain. The streets were full of troops. The least damaged buildings were used as barracks.

I was taken into a heavily-guarded place and left in a small room where two men were waiting. The three of us were alone: they stared at me, but said nothing. We waited in silence. There was only the sound of the rain beating down outside. They sat together on one bench; I, wrapped in my coat, on another. That was all the furniture in the room, which had not been cleaned. Thick dust lay over everything.

After a while they began to converse in whispers. I gathered that they had come about some post that was vacant. I stood up, started pacing backwards and forwards. I was restless, but knew I should have to wait. I was not listening to what the others were saying, but one raised his voice so that I had to hear. He was certain that he would get the job. He boasted: ‘I’ve been trained to kill with my hands. I can kill the strongest man with three fingers. I’ve learnt the points in the body where you can kill easily. I can break a block of wood with the side of my hand.’ His words depressed me. This was the kind of man who was wanted now. The two were presently called to an interview and I was left waiting alone. I was prepared to have to wait a long time.

It was not so long before a guard came to conduct me to the officers’ mess. The warden was sitting at the head of the high table. Other long tables were more crowded. I was to sit at his table, but not near him, at the far end. We should be too far apart to talk comfortably. Before taking my seat, I went up to salute him. He looked surprised and did not return my greeting. I noticed all the men sitting round immediately leaned together and began speaking in undertones, glancing furtively at me. I seemed to have made an unfavourable impression. I had assumed he would remember me, but he appeared not to know who I was. To remind him of our former connexion might make things worse, so I sat down in my distant place.

I could hear him talking amiably to the officers near him. Their conversation was of arrests and escapes. I was not interested until he told the story of his own flight, involving; big car, a snowstorm, crashing frontier gates, bullets, a girl. He never once looked in my direction or took any notice of me.

From time to time troops could be heard marching past outside. Suddenly there was an explosion. Part of the ceiling collapsed and the lights went out. Hurricane lamps were brought and put on the table. They showed fragments of plaster lying among the dishes. The food was ruined, uneatable, covered in dust and debris. It was taken away. A long and tedious wait followed; then finally bowls of hard boiled eggs were put down in front of us. Intermittent explosions continued to shake the building, a haze of whitish dust hung in the air, everything was gritty to touch.

The warden was playing a game of surprising me. He beckoned at the end of the meal. ‘I enjoyed your broadcasts. You have a gift for that sort of thing.’ I was astonished that he knew of the work I had been doing. His voice was friendly, he spoke to me as an equal, and just for a moment, I felt identified with him in an obscure sort of intimacy. He went on to say I had timed my arrival well. ‘Our transmitter will soon be in operation, and yours will be put out of action.’ I had always told the authorities we needed a more powerful installation; that it was only a question of time before the existing apparatus was jammed by a stronger one. He assumed that I had heard this was about to happen, and had defected accordingly. He wanted me to broadcast propaganda for him, which I agreed to do, if he would do something for me. ‘Still the same thing?’ ‘Yes.’ He looked at me in amusement, but suspicion flashed in his eyes. Nevertheless he remarked casually, ‘Her room’s on the floor above; we may as well pay her a visit,’ and led the way out. But when I said, ‘I have to deliver a personal message; could I see her alone?’ he did not reply.

We went down one passage, up some stairs and along another. The beam of his powerful torch played on floors littered with rubbish. Footprints showed in the dust; I looked among them for her smaller prints. He opened a door into a dimly lit room. She jumped up. Her white startled face; big eyes staring at me under glittering hair. ‘You again!’ She stood rigid, held the chair in front of her as for protection, hands clenched on the back, knuckles standing out white. ‘What do you want?’ ‘Only to talk to you.’ Looking from one of us to the other, she accused: ‘You’re in league together.’ I denied it: though in a strange way there seemed to be some truth in the charge…. ‘Of course you are. He wouldn’t bring you here otherwise.’

Читать дальше