The man drove the car brutally throughout the short day. It seemed to her that she had never known anything but this terrifying drive in the feeble half-light; the silence, the cold, the snow, the arrogant figure beside her. His cold statue’s eyes were the eyes of a Mercury, ice-eyes, mesmeric and menacing. She wished for hatred. It would have been easier. The trees receded a little, a little more sky appeared, bringing the last gleams of the fading light. Suddenly, she was astonished to see two log huts, a gate between, blocking the road. Unless the gate was opened they could not pass. She watched it racing towards them, reinforced with barbed wire and metal. The car burst through with a tremendous shattering smash, a great rending and tearing, a frantic metallic screeching. Broken glass showered her, she ducked instinctively as a long, sharp, pointed sliver sliced the air just over her head, and the car rocked sickeningly on two wheels before turning over. At the last moment then, by some miracle of skill, or strength, or sheer will power, the driver brought it back on to its axis again, and drove on as if nothing had happened.

Shouts exploded behind them. A few shots popped ineffectively and fell short. She glanced back and saw uniforms running; then the small commotion was over, cut off by black trees. The road improved on this side of the frontier, the car travelled faster, more smoothly. She shifted her position, leaning away from the stream of ice-vapour entering through the smashed window, shook bits of broken glass off her lap. There was blood on her wrists, both hands were cut and bleeding; she looked at them in remote surprise.

I raced down stairs and passages. In sight of the main door I hid in the shadows, watched the men guarding it. Sounds of the party, now growing more animated, came from the dining hall, where drinking was evidently in full swing. Someone shouted to the guards out in the cold corridor. The men I was watching put their heads together, then left their post, passed close to me as they went to join the rest. Unnoticed by anyone, I slipped out through the door they were supposed to be guarding.

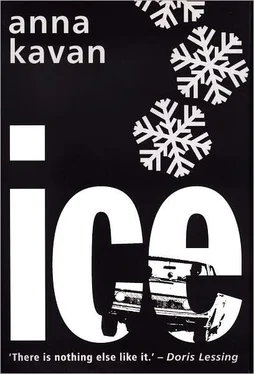

It was snowing hard. I could barely distinguish the nearest ruins, white stationary shadows beyond the moving fabric of falling white. Snowflakes turned yellow like swarms of bees round the lighted windows. A wide expanse of snow lay in front of me, a hollow marking the place where the warden’s black car had stood. I realized that various white mounds must be other cars, belonging, presumably, to his household, and waded towards them through the deep snow. I tried the door of the first one, found it unlocked. The whole vehicle was buried in snow, which had drifted deep against wheels and windscreen. Snow fell all over me when I opened the door, filled my sleeve as I tried to clean the glass. I thought the starter would never work, but at last the car began to move slowly forward. I revved the engine just enough to keep the tyres gripping, and followed the warden’s hardly visible tracks, which were rapidly being obliterated by fresh snow. Outside the encircling wall they practically vanished. I lost them altogether at the edge of the forest, blindly drove into a tree, scraping off the bark. The car stopped and refused to move. The wheels just spun round, uselessly churning the snow. As I got out, a mass of snow fell on me from the branches above. In two seconds my clothes were caked solid with driving snow. I tore down fir branches, threw them under the wheels, got back into the car and re-started. It was no good; the tyres would not grip, still went on spinning and hissing. I was sliding sideways, I pulled on the brake, jumped straight into a snowdrift, sank up to my armpits. The snow kept collapsing on me as I moved, slipped inside my collar, my shirt, I felt snow in my navel; to struggle out was an exhausting business. After breaking off more branches and piling them under the car without the least effect, I knew I was beaten and would have to give up. Weather conditions were quite impossible. Somehow or other I got the car going, and crawled back to the town. It was the only thing to do in the circumstances.

I started skidding again just as I reached the wall, lost control this time. Suddenly I saw the front wheels crumbling the edge of a deep bomb-crater; one more second, and I would be over; the drop was of many feet. I stood on the foot brake, the car spun right round, executed a complete circle before I jumped out and it nose dived, vanishing under the snow.

I was freezing, very tired, shivering so much I could hardly walk. Luckily my lodging was not far off. I slithered and staggered back there, crouched over the stove just as I was, plastered in frozen snow, my teeth chattering. The shivering was so violent I could not unfasten my coat, only succeeded in dragging it off by slow stages. In the same laborious fashion, by prolonged painful effort, I finally got rid of the rest of my freezing clothes, struggled into a dressing gown. It was then that I saw the cable and ripped open the envelope.

My informant reported the crisis due in the next few days. All air and sea services had ceased operating, but arrangements had been made to pick me up by helicopter in the morning. Still holding the flimsy paper, I crawled into bed, went on shivering under piles of blankets. The warden must have received the news earlier in the day. He had fled to save himself, abandoning his people to their fate. Of course such conduct was highly reprehensible, scandalous: but I did not condemn him. I did not think I would have acted differently in his place. Nothing he could have done would have saved the country. If he had revealed the critical situation a panic would have resulted, the roads would have been jammed, nobody would have escaped. In any case, judging by what I had just experienced, his chance of reaching the frontier was extremely slim.

The aircraft deposited me at a distant port just before the ship sailed. I was suffering from some kind of fever, shivering, aching, apathetic. I sat at the back of the car rushing me to the docks, did not even look out, went on board in a daze. The ship was already moving when I crossed the deck, meaning to go straight to my cabin. But now the scene caught my eye, and it gave me a shock; I stopped and stood staring. A sunlit harbour was sliding past me, a busy town; I saw wide streets, well-dressed people, modern buildings, cars, yachts on the blue water. No snow; no ruins; no armed guards. It was a miracle, a flashback to something dreamed. Then another shock, the sensation of a violent awakening, as it dawned on me that this was the reality, and those other things the dream. All of a sudden the life I had lately been living appeared unreal: it simply was not credible any longer. I felt a huge relief, it was like emerging into sunshine from a long cold black tunnel. I wanted to forget what had just been happening, to forget the girl and the senseless, frustrating pursuit I had been engaged in, and think only about the future.

Later, when the fever left me, my feelings remained unchanged. Thankful to have escaped from the past, I decided to go to the Indris; to make that tropical island my home, and the lemurs themselves my life work. I would devote the rest of my time to studying them, writing their history, recording their strange songs. No one else had done it, as far as I knew. It seemed a satisfactory project, a worthwhile aim.

From the shop on board I bought a big notebook and a stock of ball-point pens. I was ready to plan my work. But I could not concentrate. After all, I had not escaped the past. My thoughts kept wandering back to the girl; incredible that I should have wished to forget her. Such a forgetting would have been monstrous, impossible. She was like a part of me, I could not live without her. But now I wanted to go to the Indris, so there was a conflict. She prevented me, holding me back with thin arms.

Читать дальше