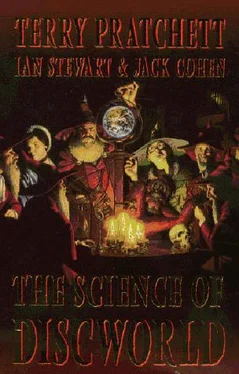

Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld I

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld I» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Science of Discworld I

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Science of Discworld I: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Science of Discworld I»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Science of Discworld I — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Science of Discworld I», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Second time round, it could easily be our branch that got pruned.

This vision of evolution as a 'contingent' process, one with a lot of random chance involved, has a certain appeal. It is a very strong way to make the point that humans are not the pinnacle of creation, not the purpose of the whole enterprise [43] In the words of Discworlcd's God of Evolution: 'The purpose of the whole thing is to be the whole thing.'

. How could we be, if a few random glitches could have swept us from the board altogether? However, Gould rather overplayed his hand (and he backed off a bit in subsequent writings). One minor problem is that more recent reconstructions of the Burgess Shale beasts suggests that their diversity may have been somewhat overrated, though they were still very diverse.

But the main hole in the argument is convergence. Evolution settles on solutions to problems of survival, and often the range of solutions is small. Our present world is littered with examples of 'convergent evolution', in which creatures have very similar forms but very different evolutionary histories. The shark and the dolphin, for instance, have the same streamlined shape, pointed snout, and triangular dorsal fin. But the shark is a fish and the dolphin is a mammal.

We can divide features of organisms into two broad classes: universals and parochials. Universals are general solutions to survival problems, methods that are widely applicable and which evolved independently on several occasions. Wings, for instance, are universals for flight: they evolved separately in insects, birds, bats, even flying fish. Parochials happen by accident, and there's no reason for them to be repeated. Our foodway crosses our airway, leading to lots of coughs and splutters when 'something goes down the wrong way'. This isn't a universal: we have it because it so happened that our distant ancestor who first crawled out of the ocean had it. It's not even a terribly sensible arrangement, it just works well enough for its flaws not to count against us when combined with everything else that makes us human. Its deficiencies were tolerated from the first fish-out-of-water, through amphibians and dinosaurs, to modern birds, and from amphibians through mammal-like reptiles to mammals like us. Because evolution can't easily 'un-evolve' major features of body-plans, we're stuck with it.

If our distant ancestors had got themselves killed off by accident, would anything like us still be around? It seems very unlikely that creatures exactly like us would have turned up, because a lot of what makes us tick is parochials. But intelligence looks like a clear case of a universal, cephalopods evolved intelligence independently of mammals, and anyway, intelligence is such a generic trick. So it seems likely that some other form of intelligent life would have evolved instead, though not necessarily adhering to the same timetable. On an alternative Earth, intelligent crabs might invent a fantasy world shaped like a shallow bowl that rides on six sponges on the back of a giant sea urchin. Three of them could at this very moment be writing The Science of Dishworld.

Sorry. But it is true. But for a fall of rock here, a tidal pattern there, we wouldn't have been us. The interesting thing is that we almost certainly would have been something else.

31. THE FUTURE IS NEWT

HEX WAS THINKING HARD AGAIN. Running the little universe was taking much less time than k had expected. It more or less ran itself now, in fact. The gravity operated without much attention, rainclouds formed with no major interference and rained every day. Balls went around one another.

HEX didn't think it was a shame about the crabs going. HEX hadn't thought it was marvellous that the crabs had turned up. HEX thought about the crabs as something that had happened. But it had been interesting to eavesdrop on Crabbity, the way the crabs named themselves, thought about the universe (in terms of crabs), had legends of the Great Crab clearly visible in the Moon, passed on in curious marks the thoughts of great crabs, and wrote down poetry about the nobility and frailty of crab life, being totally accurate, as it turned out, on this last point.

HEX wondered: if you have life, then intelligence will arise somewhere. If you have intelligence, then extelligence will arise somewhere. If it doesn't, intelligence hasn't got much to be intelligent about. It was the difference between one little oceanic crustacean and an entire wall of chalk.

The machine also wondered if it should pass on these insights to the wizards, especially since they actually lived in one of the world's more interesting outcrops of extelligence. But HEX knew that its creators were infinitely cleverer than it was. And great masters of disguise, obviously.

The Lecturer in Recent Runes had designed a creature.

'Really, all we need is a basic limpet or whelk, to begin with,' he said, as they looked at the blackboard. 'We bring it back here where proper magic works, try a few growth spells, and then let Nature take its course. And, since these extinctions seem to be wiping out everything, it'll gradually become the dominant feature.'

'What's the scale again?' said Ridcully, critically.

'About two miles to the tip of the cone,' said the Lecturer. 'About four miles across the base.'

'Not very mobile, then,' said the Dean.

'The weight of the shell will certainly hamper it, but I imagine it should be able to move its own length in a year, perhaps two.'

'What'll it eat, then?'

'Everything else.'

'Such as...'

'Everything. I'd advise suction holes around the base here so that it can filter seawater for useful things like plankton.'

'Plankton being…?'

'Oh, whales, shoals offish and so on.'

The wizards looked long and hard at the huge cone-shaped object.

'Intelligence?' said Ridcully.

'What for?' said the Lecturer in Recent Runes.

'Ah.'

'It will withstand anything except a direct hit with a comet, and I estimate it'll have a lifespan of about 500,000 years.'

'And then it'll die?' said Ridcully.

'Yes. I estimate it will, by then, take it twenty-four hours and one second to absorb enough food to last it for twenty-four hours.'

'So after that it will be dead?'

'Yes.'

'Will it know?'

'Probably not.'

'Back to the drawing board, Senior Lecturer.'

Ponder sighed.

'It's no good ducking,' he said. 'That won't help. We're paying special attention to comets. We'll let you know in plenty of time.'

'You've got no idea what it was like!' said Rincewind, creeping along the beach. 'And the noise!'

'Have you seen the Luggage?'

'It certainly made my ears ring, I can tell you!'

'And the Luggage?'

'What? Oh ... gone. Have you looked at that side of the planet? There's a whole new set of mountain ranges!'

The wizards had let time run forward for a while after the strike. It made such a depressing mess of everything. Now, drawing on its bottomless reserves of bloodimindium, life was returning in strength. Crabs were already back although, here, at least, they didn't seem inclined to make even simple structures. Perhaps something in their souls told them it'd be a waste of time in the long run.

Rincewind mentally crossed them off the list. Look for signs of intelligence, the Archchancellor had said. As far as Rincewind was concerned, anything really intelligent would be keeping out of the way of the wizards. If you saw a wizard looking at you, Rincewind would advise, then you should walk into a tree or say 'dur?'.

All along the beaches, and out below the surf, everything was acting with commendable stupidity.

A soft sound made him look down. He'd almost stepped on a fish.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Science of Discworld I»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Science of Discworld I» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Science of Discworld I» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.