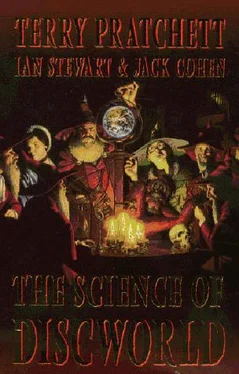

Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld I

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld I» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Science of Discworld I

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Science of Discworld I: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Science of Discworld I»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Science of Discworld I — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Science of Discworld I», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

When we look at today's organisms, some of them seem very simple while others seem more complex. A cockroach looks a lot simpler than an elephant. So we are liable to think of a cockroach as being 'primitive' and an elephant as 'advanced', or we may talk of 'lower' and 'higher' organisms. We also remember that life has evolved, and that today's complex organisms must have had simpler ancestors, and unless we are very careful we think of today's 'primitive' organisms as being typical of the ancestors of today's complex organisms. We are told that humans evolved from something that looked more like an ape, and we conclude that chimpanzees are more primitive, in an evolutionary sense, than we are.

When we do this, we confuse two different things. One is a kind of catalogue-by-complexity of today's organisms. The other is a catalogue-by-time of today's organisms, yesterday's ancestors, the day before's ancestors-of-ancestors, and so on. Although today's cockroach may be primitive in the sense that it is simpler than an elephant, it is not primitive in the sense of being an ancient ancestral organism. It can't be: it's today's cockroach, a dynamic go-ahead cockroach that is ready to face the challenges of the new millennium.

Although ancient fossil cockroaches have the same appearance as modern ones, they operated against a different backgrounds. What you needed to be a viable cockroach in the Cretaceous was probably rather different from what you need to be a viable cockroach today. In particular, the DNA of a Cretaceous cockroach was probably significantly different from the DNA of a modern cockroach. Your genes have to run very fast in order for your body to stand still.

The general picture of evolution that theorists have homed in on resembles a branching tree, with time rising like the sap from the trunk at the bottom, four billion years in the past, to the tips of the topmost twigs, the present. Each bough, branch, or twig represents a species, and all branches point upwards. This 'Tree of Life' picture is faithful to one key feature of evolution, once a branch has split, it doesn't join up again. Species diverge, but they can't merge [41] There's a silly reason for this, and a sensible one. The silly reason is that species are usually defined to be different if they don't interbreed. If two separate species don't interbreed, it's difficult to put them back together again. The sensible one is that evolution occurs by random mutations - changes to the DNA code - followed by selection. Once a change has occurred, it's unlikely for it to be undone by further random mutations. It's like driving along country roads at random, reaching some particular place, and then continuing at random. What you don't expect is to reverse your previous path and end up back where you started.

.

However, the tree image is misleading in several respects. There is, for instance, no relation between the thickness of a branch and the size of the corresponding population, the thick trunk at the bottom may represent fewer organisms, or less total organic mass, than the twig at the top. (Think about the human twig ...) The way branches split may also be misleading: it implies a kind of long-term continuity of species, even when new ones appear, because on a tree the new branches grow gradually out of the old ones. Darwin thought that speciation, the formation of new species, is generally gradual, but he may have been wrong. The theory of 'punctuated equilibrium' of Stephen Jay Gould and Niles Eldredge maintains the contrary: speciation is sudden. In fact there are excellent mathematical reasons for expecting speciation to have elements of both, sometimes sudden, sometimes gradual.

Another problem with the Tree of Life image is that many of its branches are missing, many species go unrepresented in the fossil record. The most misleading feature of all is the way humans get placed right at the top. For psychological reasons we equate height with importance (as in the phrase 'your royal highness'), and we rather like the idea that we're the most important creature on the planet. However, the height of a species in the Tree of Life indicates when it flourished, so every modern organism, be it a cockroach, a bee, a tapeworm, or a cow, is just as exalted as we are.

Gould, in Wonderful Life, objected to the 'tree' image for other reasons, and he based his objections on a remarkable series of fossils preserved in a layer of rock known as the Burgess Shale. These fossils, which date from the start of the Cambrian era [42] According to the most recent dating methods, the Cambrian began 543 million years ago. The Burgess shale was deposited about 530-520 million years ago.

, are the remains of soft-bodied creatures living on mud-banks at the base of an algal reef, which became trapped under a mudslide. Very few fossils of soft-bodied creatures exist, because normally only the harder parts survive fossilization. However, the significance of the Burgess Shale fossils went unrecognized from their discovery by Charles Walcott in 1909, until Harry Whittington took a closer look at them in 1971. The organisms were all squashed flat, and it was virtually impossible to recognize what shape they'd been while alive. Then Simon Conway Morris teased the squished layers apart, and reconstructed the original forms using a computer, and the strange secret of the Burgess Shale was revealed to the world.

Until that point, palaeontologists had classified the Burgess Shale organisms into various conventional types, worms, arthropods, whatever. But now it became clear that most of those assignments were mistaken. We knew, for example, just four conventional types of arthropod: trilobites (now extinct), chelicerates (spiders, scorpions), crustaceans (crabs, shrimp), and uniramians (insects and others). The Burgess Shale contains representatives of all of these, but it also contains twenty other radically different types. In that one mudslide, preserved in layers of shale like pressed flowers in the pages of a book, we find more diversity than in the whole of life today.

Musing on this amazing discovery, Gould realized that most branches of the Tree of Life that grew from the Burgess beasts must have 'snapped off' by way of extinction. Long ago, 20 of those 24 arthropod body plans disappeared from the face of the Earth. The Grim Reaper was pruning the Tree of Life, and being heavy-handed with the shears. So Gould suggested that a better image than a tree would be something like scrubland. Here and there 'bushes' of species sprouted from the primal ground level. Most, however, ceased to grow, and were pruned to a standstill hundreds of millions of years ago. Other bushes grew to tall shrubs before stopping ... and one tall tree made it right up to the present day. Or maybe we've reconstructed it incorrectly, amalgamating several different trees into one.

This new image changes our view of human evolution. One ani Tmal in the Burgess Shale, named Pikaia, is a chordate. This is the group that evolved into all of today's animals that have a spinal cord, including fishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals. Pikaia is our distant ancestor. Another creature in the Burgess Shale, Nectocaris, has an arthropod-like front end but a chordate back, and it has left no surviving progeny. Yet they both shared the same environment, and neither is more obviously 'fit' to survive than the other. Indeed, if one had been less evolutionarily fit, it would almost certainly have died out long before the fossils were formed. So what determined which branch survived and which didn't? Gould's suggestion was: chance.

The Burgess Shale formed on a major geological boundary: at the end of the Precambrian era and the start of the Palaeozoic. The early part of the Palaeozoic is known as the Cambrian period, and it is a time of enormous biological diversity, the 'Cambrian explosion'. The Earth's creatures were recovering from the mass extinction of the Ediacarans, and evolution took the opportunity to play new games, because for a while it didn't matter much if it played them badly. The 'selection pressure' on new body-plans was small because life hadn't fully recovered from the big die-back. In these circumstances, said Gould, what survives and what does not is mostly a matter of luck, mudslide or no mudslide, dry climate or wet. If you were to re-run evolution past this point, it's quite likely that totally different organisms would survive, different branches of the Tree of Life would be snipped off.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Science of Discworld I»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Science of Discworld I» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Science of Discworld I» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.