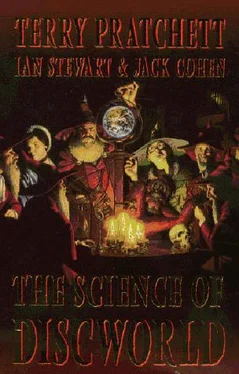

Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld I

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld I» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Science of Discworld I

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Science of Discworld I: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Science of Discworld I»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Science of Discworld I — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Science of Discworld I», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Around 1850, two people independently began to wonder whether nature might play a similar game, but on a much longer timescale and in a much grander manner, and without any sense of purpose or goal (which had been the flaw in previous musings along similar lines). They considered a self-propelled magic: 'natural' selection as opposed to selection by people. One of them was Alfred Wallace; the other, far better known today, was Charles Darwin. Darwin spent years travelling the world. From 1831 to 1836 he was hired as ship's naturalist aboard HMS Beagle, and his job was to observe plants and animals and note down what he saw. In a letter of 1877 he says that while on the Beagle he believed in 'the permanence of species', but on his return home in 1836 he began to think about the deeper meaning of what he had seen, and realized that 'many facts indicated the common descent of species'. By this he meant that species that are different now probably came from ancestors that once belonged to the same species. Species must be able to change. That wasn't an entirely new idea, but he also came up with an effective mechanism for such changes, and that was new. Meanwhile Wallace was studying the flora and fauna of Brazil and the East Indies, and comparing what he saw in the two regions, and was coming to similar conclusions, and much the same explanation. By 1858 Darwin was still mulling over his ideas, contemplating a grand publication of everything he wanted to say about the subject, while Wallace was getting ready to publish a short article containing the main idea. Being a true English gentleman, Wallace warned Darwin of his intentions so that Darwin could publish something first, and Darwin rapidly penned a short paper for the Linnaean Society, followed a year later by a book, The Origin of Species, a big book, but still not on the majestic scale that Darwin had originally intended. Wallace's paper appeared in the same journal shortly afterwards, but both papers were officially 'presented' to the Society at the same meeting.

What was the initial reaction to these two Earth-shattering articles? In his annual report for that year, the President of the Society, Thomas Bell, wrote that 'The year has not, indeed, been marked by any of those striking discoveries which at once revolutionize, so to speak, the department of science in which they occur.' However, this perception quickly changed as the sheer enormity of Darwin's and Wallace's theory began to sink in, and they took a lot of stick from Mustrum Ridcully's spiritual brethren for daring to come up with a plausible alternative to Biblical creation. What was this epoch-making alternative? An idea so simple that everybody else had missed it. Thomas Huxley is said to have remarked, on reading Origin: 'How extremely stupid not to have thought of that.'

This is the idea. You don't need a human being to push animals into new forms; they can do it to themselves, more precisely: to each other. This was the mechanism of natural selection. Herbert Spencer, who did the important journalistic job of interpreting Darwin's theory to the masses, coined the phrase, 'survival of the fittest' to describe it. The phrase had the advantage of convincing everybody that they understood what Darwin was saying, and it had the disadvantage of convincing everybody that they understood what Darwin was saying. It was a classic lie-to-children, and it deceives many critics of evolution to this day, causing them to aim at a long-disowned target, besides giving a spurious 'scientific' background to some extremely stupid and unpleasant political theories.

Starting from an enormous range of observations of many species of plants and animals, Darwin had become convinced that organisms could change of their own accord, so much so that they could even, over very long periods, change so much that they gave rise to new species.

Imagine a lot of creatures of the same species. They are in competition for resources, such as food, competing with each other, and with animals of other species. Now suppose that by random chance, one or more of these animals has offspring that are better at winning the competition. Then those animals are more likely to survive for long enough to produce the next generation, and the next generation is also better at winning. In contrast, if one or more of these animals has offspring that are worse at winning the competition, then those animals are less likely to produce a succeeding generation, and even if they somehow do, that next generation is still worse at winning. Qearly even a tiny advantage will, over many generations, lead to a population composed almost entirely of the new high-powered winners. In fact, the effect of any advantage grows like compound interest, so it doesn't take all that long. Natural selection sounds like a very straightforward idea, but words like 'competition' and 'win' are loaded. It's easy to get the wrong impression of just how subtle evolution must be. When a baby bird falls out of the nest and gets gobbled up by a passing cat, it is easy to see the battle for survival as being fought between bird and cat. But if that is the competition, then cats are clear winners, so why haven't birds evolved away altogether? Why aren't there just cats?

Because cats and birds long ago came, unwittingly, to a mutual accommodation in which both can survive. If birds could breed unchecked, there would soon be far too many birds for their food supply to support them. A female starling, for instance, lays about 16 eggs in her life. If they all survived, and this continued, the starling population would multiply by eight every generation, 16 babies for every two parents. Such 'exponential' growth is amazingly rapid: by the 70th generation a sphere the size of the solar system would be occupied entirely by starlings (instead of by pigeons, which appears to be its natural destiny).

The only 'growth rate' for the population that works is for each breeding pair of adult starlings to produce, on average, exactly one breeding pair of adult starlings. Replacement, but no more, and no less. Anything more than replacement, and the population explodes; anything less, and it eventually dies out. So of those 16 eggs, an average of 14 must not survive to breed. And that's where the cat comes in, along with all the other things that make it tough to be a bird, especially a young one. In a way, the cats are doing the birds a favour, collectively, though maybe not as individuals. (It depends if you're one of the two that survive to breed or the 14 that don't.)

Rather more obviously, the birds are doing the cats a favour, cat food literally drops out of the skies, manna from heaven. So what stops it getting out of hand is that if a group of greedy cats happens to evolve somewhere, they rapidly eat themselves out of existence again. The more restrained cats next door survive to breed, and quickly take over the vacated territory. So those cats that eat just enough birds to maintain their food supply will win a competition against the greedy cats. Cats and birds aren't competing because they're not playing the same game. The real competitions are between cats and other cats, and between birds and other birds. This may seem a wasteful process, but it isn't. A female starling has no trouble laying her 16 eggs. Life is reproductive, it makes reasonably close, though not exact, copies of itself, in quantity, and 'cheaply'. Evolution can easily 'try out' many different possibilities, and discard those that don't work. And that's an astonishingly effective way to home in on what does work.

As Huxley said, it's such an obvious idea. It caused so much trouble from religionists because it takes the gloss off one of their favourite arguments, the argument from design. Living creatures seem so perfectly put together that surely they must have been designed, and if so, there must have been a Designer. Darwinism made it clear that a process of random, purposeless variation trimmed by self-induced selection can achieve equally impressive results, so there can be the semblance of design without any Designer.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Science of Discworld I»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Science of Discworld I» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Science of Discworld I» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.