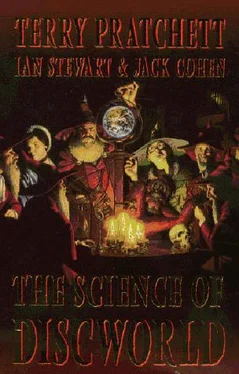

Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld I

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld I» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Science of Discworld I

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Science of Discworld I: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Science of Discworld I»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Science of Discworld I — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Science of Discworld I», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Forty million years before the Cambrian explosion, there were triploblasts on Earth, living right alongside those enigmatic Ediacarans.

We are triploblasts. Somewhere in the pre-Cambrian, surrounded by mouthless, organless Ediacarans, we came into our inheritance.

It used to be thought that life was a delicate, highly unusual phenomenon: difficult to create, easy to destroy. But everywhere we look on Earth we find living creatures, often in environments that we would have expected to be impossibly hostile. It's beginning to look as if life is an extremely robust phenomenon, liable to turn up almost anywhere that's remotely suitable. What is it about life that makes it so persistent?

Earlier we talked about two ways to get off the Earth, a rocket and a space elevator. A rocket is a thing that gets used up, but a space elevator is a process that continues. A space elevator requires a huge initial investment, but once you've got it, going up and down is essentially free. A functioning space elevator seems to contradict all the usual rules of economics, which look at individual transactions and try to set a rational price, instead of asking whether the concept of a price might be eliminated altogether. It also seems to contradict the law of conservation of energy, the physicist's way of saying that you can't get something for nothing. But, as we've seen, you can, by exploiting the new resources that become available once you get your space elevator up and running.

There is an analogy between space elevators and life. Life seems to contradict the usual rules of chemistry and physics, especially the rule known as the second law of thermodynamics, which says that things can't spontaneously get more complicated. Life does this because, like the space elevator, it has lifted itself to a new level of operation, where it can gain access to things and processes that were previously out of the question. Reproduction, in particular, is a wonderful method of getting round the difficulties of manufacturing a really complicated thing. Just build one that manufactures more of itself. The first one may be incredibly difficult, but all the rest come with no added effort.

What is the elevator for life? Let's try to be general here, and look at the common features of all the different proposals for 'the' origin of life. The main one seems to be the novel chemistry that can occur in small volumes adjacent to active surfaces. This is a long way from today's complex organisms, it's even a long way from today's bacteria, which are distinctly more complicated than their ancient predecessors. They have to be, to survive in a more complicated world. Those active surfaces could be in underwater volcanic vents. Or hot rocks deep underground. Or they could be seashores. Imagine layers of complicated (because that's easy) but disorganized (ditto) molecular gunge on rocks which are wetted by the tides and irradiated by the sun. Anything in there that happens to produce a tiny 'space elevator' establishes a new baseline for further change. For example, photosynthesis is a space elevator in this sense. Once some bit of gunge has got it, that gunge can make use of the sun's energy instead of its own, churning out sugars in a steady stream. So perhaps 'the' origin of life was a whole series of tiny 'space elevators' that led, step by step, to organized but ever more complex chemistry.

25. UNNATURAL SELECTION

THE LIBRARIAN KNUCKLED SWIFTLY through the outer regions of the University's library, although terms like 'outer' were hardly relevant in a library so deeply immersed in L-space.

It is known that knowledge is power, and power is energy, and energy is matter, and matter is mass, and therefore large accumulations of knowledge distort time and space. This is why all bookshops look alike, and why all second-hand bookshops seem so much bigger on the inside, and why all libraries, everywhere, are connected. Only the innermost circle of librarians know this, and take care to guard the secret. Civilization would not survive for long if it was generally known that a wrong turn in the stacks would lead into the Library of Alexandria just as the invaders were looking for the matches, or that a tiny patch of floor in the reference section is shared with the library in Braseneck College where Dr Whitbury proved that gods cannot possibly exist, just before that rather unfortunate thunderstorm.

The Librarian was saying 'ook ook' to himself under his breath, in the same way that a slightly distracted person searches aimlessly around the room saying 'scissors, scissors' in the hope that this will cause them to re-materialize. In fact he was saying 'evolution, evolution'. He'd been sent to find a good book on it.

He had a very complicated reference card in his mouth. The wizards of UU knew all about evolution. It was a self-evident fact. You took some wolves, and by careful unnatural selection over the generations you got dogs of all shapes and sizes. You took some sour crab-apple trees and, by means of a stepladder, a fine paintbrush and a lot of patience, you got huge juicy apples. You took some rather scruffy desert horses and, with effort and a good stock book, you got a winner. Evolution was a demonstration of narrativium in action. Things improved. Even the human race was evolving, by means of education and other benefits of civilization; it had began with rather bad-mannered people in caves, and it had now produced the Faculty of Unseen University, beyond which it was probably impossible to evolve further.

Of course, there were people who occasionally advanced more radical ideas, but they were like the people who thought the world really mas round or that aliens were interested in the contents of their underwear.

Unnatural selection was a fact, but the wizards knew, they knew, that you couldn't start off with bananas and get fish.

The Librarian glanced at the card, and took a few surprising turnings. There was the occasional burst of noise on the other side of the shelves, rapidly changing as though someone was playing with handfuls of sound, and a flickering in the air. Someone talking was replaced with the absorbent silence of empty rooms was replaced with the crackling of flame and displaced by laughter ...

Eventually, after much walking and climbing, the Librarian was faced with a blank wall of books. He stepped up to them with librarianic confidence and they melted away in front of him.

He was in some sort of study. It was book-lined, although with rather fewer than the Librarian would have expected to find in such an important node of L-space. Perhaps there was just the one book ... and there it was, giving out L-radiation at a strength the Librarian had seldom encountered outside the seriously magical books in the locked cellars of Unseen University. It was a book and father of books, the progenitor of a whole race that would flutter down the centuries ...

It was also, unfortunately, still being written.

The author, pen still in hand, was staring at the Librarian as if he'd seen a ghost.

With the exception of his bald head and a beard that even a wizard would envy, he looked very, very much like the Librarian.

'My goodness ...'

'Ook?' The Librarian had not expected to be seen. The writer must have something very pertinent on his mind.

'What manner of shade are you ... ?'

'Ook.' [36] 'Reddish-brown'.

A hand reached out, tremulously. Feeling that something was expected of him, the Librarian reached out as well, and the tips of the fingers touched.

The author blinked.

'Tell me, then,' he said, 'is Man an ape, or is he an angel?'

The Librarian knew this one.

'Ook,' he said, which meant: ape is best, because you don't have to fly and you're allowed sex, unless you work at Unseen University, worst luck.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Science of Discworld I»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Science of Discworld I» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Science of Discworld I» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.