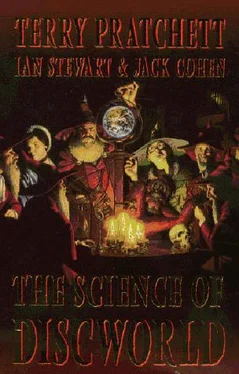

Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld I

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld I» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Science of Discworld I

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Science of Discworld I: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Science of Discworld I»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Science of Discworld I — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Science of Discworld I», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

We know the Moon is very different from the Earth in all sorts of ways. Its gravity is weaker, so it wouldn't be able to keep an atmosphere for very long, even if it had one, which it doesn't by any sensible use of the term. The Moon's surface is rock and rock dust, with no seas anywhere (water easily escapes too), although in 1997 NASA probes discovered substantial quantities of water ice at the Moon's poles, hidden from the warmth of the Sun by the permanent shadows of crater walls. That's good news for future lunar colonies, which could act as bases for the exploration of the solar system. The Moon is a good place to start from, because your spaceship doesn't need much fuel to escape the Moon's pull; the Earth is of course a bad place to start from, because down here gravity is so much stronger. How typical of humans to have evolved in the wrong place ...

How was the Moon formed? Did it condense out of the primal dustclouds along with the Earth? Did it form separately and get captured later? Are the craters extinct volcanoes, or are they marks made by lumps of rock smashing into the Moon? We know rather more about the Moon than we do about most other bodies in the solar system, because we've been there. In April 1969, Neil Armstrong stepped down on to the surface of the Moon, fluffed his lines, and made history. Between 1968 and 1972 the United States sent ten Apollo missions to the Moon and back. Of these, Apollos 8,9, and 10 were never intended to land; Apollo-11 was that historic first landing; and Apollo-13 never made it down to the surface, suffering a disastrous explosion early in its flight and turning into an excellent movie.

The rest of Apollos 11-17 landed, and between them they brought back 800 lb (400 kg) of moon rock. Most of it is still stored in the Lunar Curatorial Facility in NASA's Johnson Space Center at Clear Lake, Houston; a lot of it has never been seriously looked at at all, but what has been analysed has taught us a lot about the origins and nature of the Moon.

The Moon is about a quarter of a million miles (400,000 km) from the Earth. It is less dense than the Earth, on average, but the Moon's density is very similar to that of the Earth's mantle , a curious fact that may not be coincidence. The same side of the Moon always faces the Earth, though it wobbles a bit. The dark markings on it are called maria, Latin for 'seas', but they're not. They're flat-tish plains of rock which at one time was molten and flowed across the lunar surface like lava from a volcano. Nearly all of the craters are impact craters, where meteorites have smashed into the Moon. There are lots of them because there's a lot of rocks floating about in space, the Moon has no atmosphere to shield it by burning up the rocks through frictional heating, and the Moon has no weather to grind them back down again until they disappear. The Earth's atmosphere is a pretty good shield, but once geologists started looking they found remains of 160 impact craters down here, which is interesting given that a lot of them will have eroded away in the wind and the rain. But more of that when we get to dinosaurs.

Today the Moon always turns the same face to the Earth, which means that it rotates once round its axis every month, the same time that it takes to revolve around the Earth. (If it didn't rotate at all, it would always be pointing in the same direction, not the same direction relative to the Earth, but the same direction period. Imagine someone walking round you in a circle but always facing north, say. Then they don't always face you. In fact, you see all sides of them.) It wasn't always like this. Over hundreds of millions of years, the effect of tides has been to slow down the rotation rates of both Earth and Moon. Once the moon's rotation became synchronized with its revolutions round the Earth, the system stabilized. The moon also used to be quite a bit closer to the Earth, but over long periods of time it has moved further and further out.

Between 1600 and 1900 three theories of the formation of the Moon came into vogue and out again. One was that the Moon had formed at the same time as the Earth when the dustcloud condensed to form the solar system, Sun, planets, satellites, the whole ball of wax ... or rock, anyway. This theory, like early theories of the solar system's formation, falls foul of angular momentum. The Earth is spinning too fast, and the moon is revolving too fast, to be consistent with the Moon condensing from a dustcloud. (We misled you earlier when we said that the dustcloud theory explained the satellites too. Mostly it does, but not our enigmatic Moon. Lies-to-children, you see, now you're ready for the next layer of complication.)

Theory two was that the Moon is a piece of the Earth that broke away, maybe when the Earth was still completely molten and spinning rather fast. That theory bounced into the bin because nobody could find a pkusible way for a spinning molten Earth to eject anything that would remotely resemble the Moon, even if you waited a bit for things to cool down.

According to theory three, the Moon formed elsewhere in the solar system, and was wandering along when it happened to come within the Earth's gravitational clutches and couldn't get out again. This theory was very popular, even though gravitational capture is distinctly tricky to arrange. It's a bit like trying to throw a golfball into the hole so that it goes round and round just inside the rim. What usually happens is that it falls to the bottom (collides with the Earth) or does what every golfer has experienced to their utter horror, and goes in for a split second before climbing back out again (escapes without being captured).

The rock samples from Apollo missions added to the mystery of the Moon's origins. In some respects, Moon rock is astonishingly similar to Earth rock. If they were similar in most respects, this would be evidence for a common origin, and we'd have to take another look at the theory that they both condensed from the same dustcloud. But Moon rock doesn't resemble all Earth rock, only the mantle. The current theory, which dates from the early 1980s, is that the Moon was once part of the Earth's mantle. It wasn't ejected as a result of the Earth's spin: it was knocked into space about four billion years ago when a giant body, about the size of Mars, struck the early Earth a glancing blow. Computer calculations show that such an impact can, if conditions are right, strip a large chunk of mantle from the Earth, and sort of smear it out into space. This takes about 13 minutes (aren't computers good?). Then the ejected mantle, which is molten, begins to condense into a ring of rocks of various sizes. Some of it forms a big lump, the proto-Moon, and this quickly sweeps up most of the rest. What's left doesn't go away so easily, however, but over 100 million years nearly all of it crashes into either the Moon or the Earth, because of gravity.

Because Earth has weather, especially back then, oh boy, did it have weather then, the resulting impact craters all got eroded away; but because the Moon has no weather, the lunar impact craters didn't get eroded away, and a lot of them are still there now. The great charm of this theory is that it explains many different features of the Moon in one go, its similarity to the Earth's mantle, the fact that its surface seems to have undergone a sudden and extreme amount of heating about 4 billion years ago, its craters, its size, its spin, even those sea-like maria, released as the proto-Moon slowly cooled. The early solar system was a violent place.

In fact, the Dean's mis-designed sun might have done us some good after all ...

The Moon affects life on Earth in at least two or three ways that we know of, probably dozens more that we haven't yet appreciated.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Science of Discworld I»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Science of Discworld I» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Science of Discworld I» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.