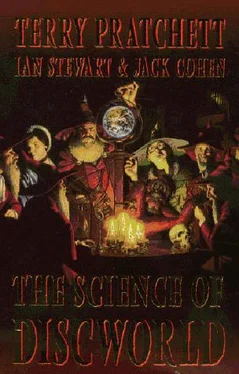

Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld I

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld I» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Science of Discworld I

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Science of Discworld I: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Science of Discworld I»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Science of Discworld I — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Science of Discworld I», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The difficulties involved in being sure are many. We don't have good records of past levels of carbon dioxide, so we lack a suitable 'benchmark' against which to assess today's levels, although we're beginning to get a clearer picture thanks to ice cores drilled up from the Arctic and Antarctic, which contain trapped samples of ancient atmospheres. If 'global warming' is under way, it need not show up as an increase in temperature anyway (so the name is a bit silly). What it shows up as is climatic disturbance. So even though the six warmest summers in Britain this century have all occurred in the nineties, we can't simply conclude that 'it's getting warmer', and hence that global warming is a fact. The global climate varies wildly anyway, what would it be doing if we weren't here?

A project known as Biosphere II attempted to sort out the basic science of oxygen/carbon transactions in the global ecosystem by setting up a 'closed' ecology, a system with no inputs, beyond sunlight, and no outputs whatsoever. In form it was like a gigantic futuristic garden centre, with plants, insects, birds, mammals, and people living inside it. The idea was to keep the ecology working by choosing a design in which everything was recycled.

The project quickly ran into trouble: in order to keep it running, it was necessary to keep adding oxygen. The investigators therefore assumed that somehow oxygen was being lost. This turned out to be true, in a way, but for nowhere near as literal a reason. Even though the whole idea was to monitor chemical and other changes in a closed system, the investigators hadn't weighed how much carbon they'd introduced at the start. There were good reasons for the omission, mostly, it's extremely difficult, since you have to estimate carbon content from the wet weight of live plants. Not knowing how much carbon was really there to begin with, they couldn't keep track of what was happening to carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide. However, 'missing' oxygen ought to show up as increased carbon dioxide, and they could monitor the carbon dioxide level and see that it wasn't going up.

Eventually it turned out that the 'missing' oxygen wasn't escaping from the building: it was being turned into carbon dioxide. So why didn't they see increased carbon dioxide levels? Because, unknown to anybody, carbon dioxide was being absorbed by the building's concrete as it 'cured'. Every architect knows that this process goes on for ten years or so after concrete has set, but this knowledge is irrelevant to architecture. The experimental ecologists knew nothing about it at all, because esoteric properties of poured concrete don't normally feature in ecology courses, but to them the knowledge was vital.

Behind the unwarranted assumptions that were made about Biosphere II was a plausible but irrational belief that because carbon dioxide uses up oxygen when it is formed, then carbon dioxide is opposite to oxygen. That is, oxygen counts as a credit in the oxygen budget, but carbon dioxide counts as a debit. So when carbon dioxide disappears from the books, it is interpreted as a debt cancelled, that is, a credit. Actually, however, carbon dioxide contains a positive quantity of oxygen, so when you lose carbon dioxide you lose oxygen too. But since what you're looking for is an increase in carbon dioxide, you won't notice if some of it is being lost.

The fallacy of this kind of reasoning has far wider importance than the fate of Biosphere II. An important example within the general frame of the carbon/oxygen budget is the role of rainforests. In Brazil, the rainforests of the Amazon are being destroyed at an alarming rate by bulldozing and burning. There are many excellent reasons to prevent this continuing, loss of habitat for organisms, production of carbon dioxide from burning trees, destruction of the culture of native Indian tribes, and so on. What is not a good reason, though, is the phrase that is almost inevitably trotted out, to the effect that the rainforests are the 'lungs of the planet'. The image here is that the 'civilized' regions, that is, the industrialized ones, are net producers of carbon dioxide. The pristine rainforest, in contrast, produces a gentle but enormous oxygen breeze, while absorbing the excess carbon dioxide produced by all those nasty people with cars. It must do, surely? A forest is full of plants, and plants produce oxygen.

No, they don't. The net oxygen production of a rainforest is, on average, zero. Trees produce carbon dioxide at night, when they are not photosynthesizing. They lock up oxygen and carbon into sugars, yes, but when they die, they rot, and release carbon dioxide. Forests can indirectly remove carbon dioxide by removing carbon and locking it up as coal or peat, and by releasing oxygen into the atmosphere. Ironically, that's where a lot of the human production of carbon dioxide comes from, we dig it up and burn it again, using up the same amount of oxygen.

If the theory that oil is the remains of plants from the carboniferous period is true, then our cars are burning up carbon that was once laid down by plants. Even if an alternative theory, growing in popularity, is true, and oil was produced by bacteria, then the problem remains the same. Either way, if you burn a rainforest you add a one-off surplus of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere, but you do not also reduce the Earth's capacity to generate new oxygen. If you want to reduce atmospheric carbon dioxide permanently, and not just cut short-term emissions, the best bet is to build up a big library at home, locking carbon into paper, or put plenty of asphalt on roads. These don't sound like 'green' activities, but they are. You can cycle on the roads if it makes you feel better.

Another important atmospheric component is nitrogen. It is a lot easier to keep track of the nitrogen budget. Organisms, plants especially, as every gardener knows, need nitrogen for growth, but they can't just absorb it from the air. It has to be 'fixed', that is, combined into compounds that organisms can use. Some of the fixed nitrogen is produced as nitric acid, which rains down after thunderstorms, but most nitrogen fixation is biological. Many simple lifeforms 'fix' nitrogen, using it as a component of their own amino-acids. These amino-acids can then be used in everybody else's proteins.

The Earth's oceans contain a huge quantity of water, about a third of a billion cubic miles (1.3 billion cubic km). How much water there was in the earliest stages of the Earth's evolution, and how it was distributed over the surface of the globe, we have little idea, but the existence of fossils from about 3.3 billion years ago shows that there must have been water around at that time, probably quite a lot. As we've already explained, the Earth, along with the rest of the solar system, Sun included, condensed from a vast cloud of gas and dust, whose main constituent was hydrogen. Hydrogen combines readily with oxygen to form water, but it also combines with carbon to form methane and with nitrogen to form ammonia.

The primitive Earth's atmosphere contained a lot of hydrogen and a fair quantity of water vapour, but initially the planet was too hot for liquid water to exist. As the planet slowly cooled, its surface passed a critical temperature, the boiling point of water. That temperature was probably not exactly the same as the one at which water boils now; in fact even today it's not one inflexible temperature, because the boiling point of water depends on pressure and other circumstances. Nor was it just a simple matter of the atmosphere's getting colder: its composition also changed because the Earth was spouting out gases from its interior through volcanic activity.

A crucial factor was the influence of sunlight, which split some of the atmospheric water vapour into oxygen and hydrogen. The hydrogen escaped from the Earth's relatively weak gravitational field, so the proportion of oxygen got bigger while that of water vapour got smaller. The effect of this was to increase the temperature at which the water vapour could condense. So as the temperature of the atmosphere slowly fell, the temperature at which water vapour would condense rose to meet it. Eventually the atmosphere going down passed the boiling point of water going up, and water vapour began to condense into liquid water ... and to fall as rain.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Science of Discworld I»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Science of Discworld I» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Science of Discworld I» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.