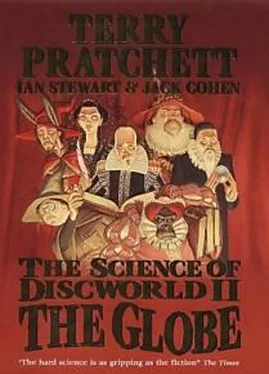

Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld II - The Globe

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld II - The Globe» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Science of Discworld II - The Globe

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Science of Discworld II - The Globe: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Science of Discworld II - The Globe»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Science of Discworld II - The Globe — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Science of Discworld II - The Globe», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

'Aha,' said the Dean. 'I think I can see this one ...'

Niklias nodded. 'My master commanded many changes before the device functioned to his satisfaction ... many gears and rollers and cranks, much rebuilding of strange mechanisms, much profanity which, I have no doubt, the gods noted. But finally we suspended the well-trained horse in its sling and the rider urged it into a trot as the cloth rolled beneath. And, yes, afterwards, oh sad that day, we measured the length of the cloth where the horse had trotted and the length of the smears of charcoal where a hoof had pressed on the cloth and ... I hardly dare say it, even now, the total length of the second was to the length of the first was as four is to five.'

'So for a fifth of the time all hooves were in the air!' said the Dean. Well done! I love a puzzle!'

'No, it was not well done!' shouted the slave. 'My master ranted! We did it again and again! And it was always the same!'

'I don't quite see the problem—' Ridcully began.

'He tore at his hair and raved at us, and most of the men fled! And then he went and sat in the waves on the shore, and after a long while I dared to go and speak to him, and he turned hollow eyes on me and said, "Great Antigonus is wrong. I proved him wrong! Not by thoughtful dispute, but by gross mechanical contrivances! I am ashamed! He is the greatest of philosophers! He had told us that the sun goes around the world, he had told us how the planets move! And if he is wrong, what is right? What have I done? I have squandered the wealth of my family. What fame is there for me now? What cursed work shall I do next? Should I steal the colours from a flower?

Shall I say to everyone, 'What you think is right, is not right'? Shall I weigh the stars? Shall I plumb the utter depths of the sea? Shall I ask the poet to measure the width of love and the direction of pleasure? What have I made of myself ..." and he wept.'

There was silence. None of the wizards moved.

Niklias settled down a little. 'And then he bade me go back and he told me to take the little money that was left. In the morning he was gone. Some say he fled to Egypt, some say to Italy.

But for myself. I think he did indeed plumb, at the last, the depth of the sea. For I do not know what he was, or what he had become. And presently people came and tore down most of the engines.'

He shifted his weight and looked at the remains of the strange devices, skeletal against the livid sunset. There was something wistful in his expression.

'No one comes now,' he said. 'Hardly anyone at all. This is where the Fates struck and the gods laughed at men. But I remember how he wept. And so I remain, to tell the story.'

22. THE NEW NARRATIVIUM

The wizards have been trying to find some 'psyence' in Roundworld, but it is proving even more elusive than the correct spelling. They are having problems because they are tackling a difficult question. There isn't a simple definition of 'science' that really captures what it is. And it's not the sort of thing that comes into existence at a single place and time. The development of science was a process in which non-science slowly became science. The two ends of the process are easily distinguished, but there's no special place in between where science suddenly came into being.

These difficulties are more common than you might expect. It is almost impossible to define a concept precisely -think of 'chair', for example. Is a large beanbag a chair? It is if the designer says it's a chair and someone uses it to sit on; it's not if a bunch of kids are throwing it at each other. The meaning of 'chair' does not just depend on the thing to which it is being applied: it also depends on the associated context. And as for processes in which something gradually changes into something else ... well, we're never comfortable with those. At what stage in its life does a developing embryo become a human being, for instance? Where do you draw the line?

You don't. If the end of a process is qualitatively different from the start, then something changes in between. But it need not be at a specific place in between, and if the change is gradual, there isn't a line. Nobody thinks that when an artist is painting something, there is one special stroke of the brush at which it turns into a picture. And nobody asks 'Whereabouts in that particular brushstroke does the change take place?' At first there is a blank canvas, later there's a picture, but there isn't a well-defined moment at which one ceases and the other begins. Instead, there is a long period of neither.

We accept this about a painting, but when it comes to more emotive processes like embryos becoming human beings, a lot of us still feel the need to draw a line. And the law encourages us to think like that, in black and white, with no intervening shades of grey. But that's not how the universe works. And it certainly didn't work like that for science.

To complicate things even further, important words have changed their meaning. An old text from 1340 states that 'God of sciens is lord', but there the word [57] Other recorded spellings are cience, ciens, scians, scyence, sience, syence, syens, syense, scyense. Oh, and science. Naturally, the wizards have invented another one.

'sciens' means 'knowledge', and the phrase is saying that God is lord of knowledge. For a long time science was known as 'natural philosophy', but by 1725 the word 'science' is being used in essentially its modern form. The word 'scientist', however, seems to have been invented by William Whewell in his 1840 The Philosophy of the Inductive Sciences to describe a practitioner of science. But there were scientists before Whewell invented a word for them, otherwise he wouldn't have needed a word, and there was no science when God was lord of knowledge. So we can't just go by the words people use, as if words never change their meanings, or as if things can't exist before we have a word for them.

But surely science goes back a long, long way? Archimedes was a scientist, wasn't he? Well, it depends. It certainly looks to us, now, as if Archimedes was doing science; indeed we have reached back into history, picked out some of his work (especially his buoyancy principle) and called it science. But he wasn't doing science then, because the context wasn't suitable, and his mind-set was not 'scientific'. We see him with hindsight; we turn him into something we recognise, but he wouldn't.

Archimedes made a brilliant discovery, but he didn't test his ideas like a scientist would now, and he didn't investigate the problem in a genuinely scientific way. His work was an important step along the path to science, but one step is not a path. And one thought is not a way of thinking.

What about the Archimedean screw? Was that science? This wonderful device is a helix that fits tightly inside a cylinder. You place the cylinder at a slant, with the bottom end in water; turn the helix, and after a while water comes out at the top. It is generally believed that the famous Hanging Gardens of Babylon were watered using massive Archimedean screws. How it works is more subtle than Ridcully imagines: in particular, the screw ceases to work if it is held at too steep an angle. Rincewind is right: an Archimedean screw is like a series of travelling buckets, separate compartments with water in them. Because they are separate, there is no continuous channel for the water to flow away along. As the screw turns, the compartments move up the cylinder, and the water has to go with them. If you hold the cylinder at too steep a slope, all the

'buckets' merge, and the water no longer climbs.

The Archimedean screw surely counts as an example of ancient Greek technology, and it illustrates their possession of engineering. We tend to think of the Greeks as 'pure thinkers', but that's the result of selective reporting. Yes, the Greeks were renowned for their (pure)

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Science of Discworld II - The Globe»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Science of Discworld II - The Globe» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Science of Discworld II - The Globe» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.