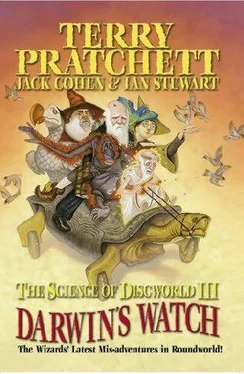

Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Erasmus, a physician, could also turn a nifty hand to machinery, and he invented a new steering mechanism for carriages, a horizontal windmill to grind Josiah's pigments, and a machine that could speak the Lord's Prayer and the Ten Commandments. When the 1791 riots against `philosophers' (scientists) and for `Church and King' put paid to the Lunar Society, Erasmus was just putting the finishing touches to a book. Its title was Zoonomia, and it was about evolution.

Not, however, by Charles's mechanism of natural selection. Erasmus didn't really describe a mechanism. He just said that organisms could change. All plant and animal life, Erasmus thought, derived from living `filaments'. They had to be able to change, otherwise they'd still be filaments. Aware of Lyell's Deep Time, Erasmus argued that: In the great length of time, since the earth began to exist, perhaps millions of ages before the commencement of the history of mankind, would it be too bold to imagine, that all warm-blooded animals have arisen from one living filament, which the first great cause endowed with animality, with the power of acquiring new parts, attended by new propensities, directed by irritations, sensations, volitions, and associations; and thus possessing the faculty of continuing to improve by its own inherent activity, and of delivering down those improvements by generation to its posterity, world without end! If this sounds Lamarckian, that's because it was. Jean-Baptiste Lamarck believed that creatures could inherit characteristics acquired by their ancestors - that if, say, a blacksmith acquired huge muscular arms by virtue of working for years at his forge, then his children would inherit similar arms, without having to do all that hard work. Insofar as Erasmus envisaged a mechanism for heredity, it was much like Lamarck's. That did not prevent him having some important insights, not all of them original. In particular, he saw humans as superior descendants of animals, not as a separate form of creation. His grandson felt the same, which is why he called his later book on human evolution The Descent of Man. All very proper and scientific. But Ridcully is right. `Ascent' would have been better public relations.

Charles certainly read Zoonomia, during the holidays after his first year at Edinburgh University. He even wrote the word on the opening page of his `B Notebook', the origin of Origin. So his grandfather's views must have influenced him, but probably only by affirming the possibility of species change [47] What would have happened - if Darwin had gone back in time and killed his own grandfather?

. The big difference was that from the very beginning, Charles was looking for a mechanism. He didn't want to point out that species could change - he wanted to know bow they changed. And it is this that distinguishes him from nearly all of the competition.

The most serious competitor we have mentioned already: Wallace. Darwin acknowledges their joint discovery in the second paragraph of the introduction to Origin. But Darwin wrote an influential and controversial book, whereas Wallace wrote one short paper in a technical journal. Darwin took the theory much further, assembled much more evidence, and paid more attention to possible objections.

He prefaced Origin with `An Historical Sketch' of views of the origin of species, and in particular their mutability. A footnote mentions a remarkable statement in Aristotle, who asked why the various parts of the body fit together, so that, for example, the upper and lower teeth meet tidily, instead of grinding against each other. The ancient Greek philosopher anticipated natural selection: Wheresoever, therefore, all things together (that is all the parts of one whole) happened like as if they were made for the sake of something, these were preserved, having been appropriately constituted by an internal spontaneity; and whatsoever things were not thus constituted, perished, and still perish.

In other words: if by chance, or some unspecified process the components carried out some useful function, they would appear in later generations, but if they didn't, the creature that possessed them would not survive.

Aristotle would have made short shrift of Paley.

Next, Darwin tackles Lamarck, whose views date from 1801. Lamarck contended that species could descend from other species, mostly because close study shows endless tiny graduations and varieties within a species, so the boundaries between distinct species is much fuzzier than we usually think. But Darwin notes two flaws. One is the belief that acquired characteristics can be inherited - Darwin cites the giraffe's long neck as an example. The other is that Lamarck believed in `progress' - a one-way ascent to higher and higher forms of organisation.

A long series of minor figures follows. Among them is one noteworthy but obscure fellow, Patrick Matthew. In 1831, he published a book about naval timber, in which the principle of natural selection was stated in an appendix. Naturalists failed to read the book, until Matthew drew attention to his anticipation of Darwin's central idea in the Gardener's Chronicle in 1860.

Now Darwin introduces a better-known forerunner, the Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation. This book was published anonymously in 1844 by Robert Chambers; it is clear that he was also its author. The medical schools of Edinburgh were awash with the realisation that entirely different animals have remarkably similar anatomies, suggesting a common origin and therefore the mutability of species. For example, the same basic arrangement of bones occurs in the human hand, the paw of a dog, the wing of a bird, and the fin of a whale. If each were a separate creation, God must have been running out of ideas.

Chambers was a socialite - he played golf - and he decided to make the scientific vision of life on Earth available to the common man. A born journalist, Chambers outlined not just the history of life, but that of the entire cosmos. And he filled the book with sly digs at `those dogs of the clergy'. The book was an overnight sensation, and each successive edition slowly removed various blunders that had made the first edition easy to attack on scientific grounds. The vilified clergy thanked their God that the author had not begun with one of the later editions.

Darwin, who respected the Church, had to refer to Vestiges, but he also had to distance himself from it. In any case, he found it woefully incomplete. In his `Historical Sketch', Darwin quoted from the tenth `and much improved' edition, objecting that the anonymous author of Vestiges cannot account for the way organisms are adapted to their environments or lifestyles. He takes up the same point in his introduction, suggesting that the anonymous author would presumably say that: After a certain number of unknown generations, some bird had given birth to a woodpecker, and some plant to the misseltoe {sic}, and that these had been produced perfect as we now see them; but this assumption seems to me to be no explanation, for it leaves the case of the coadaptations of organic beings to each other and to their physical conditions of life, untouched and unexplained.

More heavyweights follow, interspersed with lesser figures. The first heavyweight is Richard Owen, who was convinced that species could change, adding that to a zoologist the word `creation' means `a process he knows not what'. The next is Wallace. Darwin reviews his interactions with both, at some length. He also mentions Herbert Spencer, who considered the breeding of domesticated varieties of animals as evidence that species could change in the wild, without human intervention. Spencer later became a major populariser of Darwin's theories. He introduced the memorable phrase `survival of the fittest', which unfortunately has caused more harm than good to the Darwinian cause, by promoting a rather simple-minded version of the theory.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.