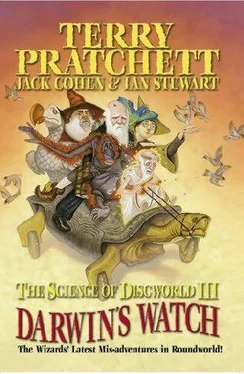

Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Was Darwin just another Watt? Did he get credit for evolution because he brought it into a polished, effective form? Is he famous because we happen to know so much about his personal history? Darwin was an obsessive record-keeper, he hardly threw away a single scrap of paper. Biographers were able to document his life in exceptional detail. It certainly did his reputation no harm that such a wealth of historical material was available.

In order to make comparisons, let's review the history of the steam engine, avoiding lies-to-children as much as we can. Then we'll look at Darwin's intellectual predecessors, and see whether a common pattern emerges. How does steam engine time work? What factors lead to a cultural explosion, as an apparently radical idea `takes off and the world changes for ever? Does the idea change the world, or does a changing world generate the idea?

Watt completed his first significant steam engine in 1768, and patented it in 1769. It was preceded by various prototypes. But the first recorded reference to steam as a source of motive power occurs in the civilisation of ancient Egypt, during the Late Kingdom when that country was under Roman rule. Around 150 BC (the date is very approximate) Hero of Alexandria wrote a manuscript Spiritalia seu Pneumatica. Only partial copies have survived to the present day, but from them we learn that the manuscript referred to dozens of steam-driven machines. We even know that several of them predated Hero, because he tells us so; some were the previous work of the inventor Cestesibus, celebrated for the great number and variety of his ingenious pneumatic machines. So we can see the beginnings of steam engine time long ago, but initial progress was so quiet and slow that steam engine time itself was still far in the future.

One of Hero's devices was a hollow airtight altar, with the figure of a god or goddess on top, and a tube running through the figure. Unknown to the punters, the altar contains water. When a worshipper lights a fire on top of the altar, the water heats up and produces steam. The pressure of the steam drives some of the remaining liquid water up the pipe, and the god offers a libation. (As miracles go this one is quite effective, and distinctly more convincing than a statue of a cow that oozes milk or one of a saint that weeps.) Similar devices were commonplace from the 1960s to make tea at the bedside and pour it out automatically. They still exist today, but are harder to find.

Another of Hero's machines used the same principle to open a temple door when someone lit a fire on an altar. The device is quite complicated, and we describe it to show that these ancient machines went far beyond being mere toys. The altar and door are above ground, the machinery is concealed beneath. The altar is hollow, filled with air. A pipe runs vertically down from the altar into a metal sphere full of water, and a second inverted U-shaped pipe acts like a siphon, with one end inside the sphere and the other inside a bucket. The bucket hangs over a pulley, and ropes from the bucket wind round two vertical cylinders, in line with the hinges of the door and attached to the door's edge. They then run over a second pulley and terminate in a heavy weight which acts as a counterbalance. When a priest lights the fire, the air inside the altar expands, and the pressure drives water out of the sphere, through the siphon, and into the bucket. As the bucket descends under the weight of water, the ropes cause the cylinders to turn, opening the doors.

Then there's a fountain that operates when the sun's rays fall on it, and a steam boiler that makes a mechanical blackbird sing or blows a horn. Yet another device, often referred to as the world's first steam engine, boils water in a cauldron and uses the steam to turn a metal globe about a horizontal axis. The steam emerges from a series of bent pipes around the sphere's `equator', at right angles to the axis.

In design, these machines weren't toys, but as far as their applications went, they might as well have been. Only the door-opener comes close to doing anything we would consider practical, although the priests probably found the ability to produce miracles on demand to be quite profitable, and that's practical enough for most businessmen today.

Looking back from the twenty-first century, it seems astonishing that it took steam engine time so long to gain proper momentum, with all these examples of steam power on public display all over the ancient world. Especially since there was plenty of demand for mechanical power, for the same reasons that finally gave birth to steam engine technology in the eighteenth century - pumping water, lifting heavy weights, mining, and transport. So we learn that it takes more than the mere ability to make steam engines, even in conjunction with a clear need for something of that kind, to kick-start steam engine time.

And so the steam engine bumbled along, never disappearing entirely, but never making any kind of breakthrough. In 1120 the church at Rheims had what looks suspiciously like a steam-powered organ. In 1571 Matthesius described a steam engine in a sermon. In 1519 the French academic Jacob Besson wrote about the production of steam and its mechanical uses. In 1543 the Spaniard Balso de Garay is reputed to have suggested the use of steam to power a ship. Leonardo da Vinci described a steam-gun that could throw a heavy metal ball. In 1606 Florence Rivault, gentleman of the bedchamber to Henry IV, discovered that a metal bombshell would explode if it was filled with water and heated. In 1615, Salomon de Caius, an engineer under Louis XIII, wrote about a machine that used steam to raise water. In 1629 ... but you get the idea. It went on like that, with person after person reinventing the steam engine, until 1663.

In that year Edward Somerset, Marquis of Worcester, not only invented a steam-powered machine for raising water: he got it built, and installed, two years later, at Vauxhall - now part of London, but then just outside it. This was probably the first genuine application of steam power to a serious practical problem. No drawing of the machine exists, but its general form has been inferred from grooves, still surviving, in the walls of Raglan Castle, where it was installed. Worcester planned to form a company to exploit his machine, but failed to raise the cash. His widow in her turn made the same attempt, with the same lack of success. So that's another necessary ingredient for steam engine time: money.

In some ways, Worcester was the true creator of the steam engine, but he gets little credit, because he was just a tiny bit ahead of the wave. He does mark a moment at which the whole game changed, however: from this point on, people didn't just invent steam engines - they used them. By 1683, Sir Samuel Morland was building steampowered pumps for Louis XIV, and his book of that year reveals a deep familiarity with the properties of steam and the associated mechanisms. The idea of the steam engine had now arrived, along with a few of the things themselves, earning their living by performing useful tasks. But it still wasn't steam engine time.

Now, however, the momentum began to grow rapidly, and what gave it a really big push was mining. Mines, for coal or minerals, had been around for millennia, but by the start of the eighteenth century they were becoming so big, and so deep, that they ran into what quickly became the miner's greatest enemy: water.

The deeper you try to dig mines, the more likely they are to become flooded, because they are more likely to run into underlying reservoirs of water, or cracks that lead to such reservoirs, or just cracks down which water from above can flow. Traditional methods of removing water were no longer successful, and something radically different was needed. The steam engine filled the gap neatly. Two people, above all, made it possible to build suitable machinery: Dennis Papin and Thomas Savery.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.