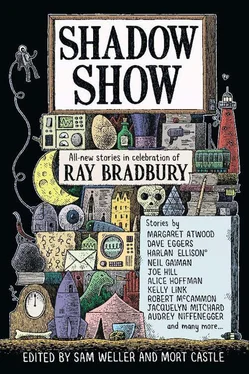

Ray Bradbury taught me that the secret of writing was the secret of life. Look closely. Be generous. Be honest with genuine emotion. Remember the details. Observe the impossible through the filter of the possible. Show but don’t manipulate.

Now Mr. Bradbury is ninety-two.

Not long ago I read “I Sing the Body Electric!” to my son Will, a second-grader and the seventh of my nine children. The story is not cloying. It was not then. It has not aged. It had not then. It is as subtly humorous and precise as it ever was, and as heartbreaking.

“Wouldn’t it be nice if we could put you away until we were old grandpas?” Will asked, with the icy candor of childhood.

“It sure would,” I said. “But maybe it would be better to put Daddy’s mother away.”

I’m not bad with icy candor myself.

But it would. It would all be good. Ray Bradbury’s worlds are fierce and sometimes violent, but they are never vile. Whatever events befall the characters, they do so within the gentle protectorate of a man who, as a writer, valued human dignity and warned of human foibles and believed that humor must inform both.

When I was nearly forty, more than fifteen years after that first note, I sent Mr. Bradbury a copy of my first novel. I did not expect him to write back. He had been ill, I’d heard, and had only recently gotten better. However, a week later, I received a note written in his own hand. It read, Well. I was correct. Wasn’t I?

As it seemed to me then, and later, and now, I suppose he was and is right—in most ways.

When I sat down to write my first tale of terror, “Two of a Kind” (presented here, for your approval), I followed the example of Ray Bradbury on the deepest level, perhaps without really realizing how much I was thinking of him.

Some of the strangest details of the story of the Nickolai family came from my own colorful tree. My grandmother really did have twin cousins who married brothers; and the boy who robbed the tomb of the Gypsy queen lived to regret it. Other events in the story were borrowed from the lives of others, including the five Irish sisters, four of whom entered the convent (although none was a teleporting vampire).

I kept things humble. A rusty knife. A lame leg. A plumber, like my father, in business with his brother-in-law, like my father. A two-flat in a neighborhood whose sounds and smells and sights I know as well as my prayers.

Perhaps as a result, I love this story. I all but admire it, almost as though someone else’s hand inspired and guided it.

Maybe someone else’s hand did guide it.

Ray Bradbury has many children, and many heirs.

—Jacquelyn Mitchard

FAT MAN AND LITTLE BOY

Gary A. Braunbeck

Setting down the bulky square insulated bag, the little boy used his key to unlock the back door, looking around to make sure no one had followed him, and let himself into the house—more specifically, the kitchen. He pulled plates and glasses from the cupboards, removed knives, forks, and spoons from the cutlery drawer, hauled four large bottles of soda pop (still unopened) from the colossal refrigerator and two sizeable trays from the counter, which he immediately positioned on the rolling metal serving cart. It usually took him fifteen minutes to get everything ready; today it took less than ten. He was nervous and a bit frightened. He was afraid this might be his last time visiting this house.

Positioning everything on the trays so the cart was not off balance, he rolled through the kitchen doorway, took a left, and made his way into the fat man’s enormous living room.

“Well, hello there, boy,” said the fat man from his bed, which was really four , all king-sized, all pushed together to make a bed the size of two parked flatbed trucks. The fat man’s upper body was held up by about a thousand pillows because if he were ever to lie all the way down, he would not be able to breathe. He always had trouble breathing, so he kept a tall oxygen tank next to the bed.

“Hello, sir,” replied the little boy, rolling the cart up to the side of the fat man’s bed, careful not to knock over the oxygen tank. “I got the pizzas like you wanted. Double cheese and pepperoni and hamburger and onions and green peppers on all four of them.” He twisted off the cap on the first two-liter bottle of soda pop and poured glasses for himself and the fat man.

“Did anybody follow you here?”

The little boy shook his head and prepared the fat man’s first tray. “I don’t think so. I took a bunch of shortcuts. I got lots of them all over.” He reached into his pocket. “I got your change.”

“You keep it.”

“But it’s almost twenty dollars !”

“We’ll call it hazard pay and let my accountants throw hissy fits over it.”

“Thank you. Now I’m really glad I took all those shortcuts.”

The fat man smiled. “I knew you were a wise one, my boy. Don’t ever listen to those cretins who make fun of you, be it at home or at school.” He accepted the first glass of pop, remembering at the last second to remove his oxygen mask before taking the first gulp. “Ahhh, refreshing.” He watched as the little boy prepared the first tray for this feast. “Hell of a world out there now, isn’t it? Hell of a world. All of those beautiful people, hale and hearty and happy, and all of them so much the very right size. Wasn’t enough that all of the movies and television shows and commercial and magazines showed only people with perfectly aligned white teeth whose bodies were so flawless it was almost stupid, nosiree. They had to go and—bear in mind, boy, this was long before you were born, so I’m guessing you’ve never heard of this—they had to go and pass laws saying that individuals like myself, that is, persons of the ‘larger-than-legal’ body size, we beached whales, we human obesedons, we well-padded folk who are resplendent in our Tubby-the-Tuba-like corpulescence—and if that’s not an actual word, it damn well ought to be, don’t you think?—they passed laws stating in murky yet curiously adjective-heavy legalese that we of the you-should-pardon-the-expression jiggly ginormous girth guild were not allowed to leave our homes until such time that our bodies were of a more, oh, how did they phrase it? Ah, yes, I have it now, ‘aesthetically agreeable appearance.’ Foolhardy flibbertigibbets, the lot of them. It’s enough to make a man lose his appetite.” He winked. “Just not this one.”

The little boy smiled as he finished preparing the first tray. The fat man had a wonderful way of talking. It always made the little boy smile. When he went home after these visits, he often wrote down many of the things—the “pearls of wide-load wisdom” as the fat man called them—that his large friend imparted. The fat man talked to him like he was a real person, not some child who everyone made fun of and spoke to in that awful little-baby voice. He liked that. He liked that right down to the ground.

“Well, don’t just stand there gawking,” said the fat man. “My God, Fedor Jeftichew—better known as Jo-Jo the Dog-Faced Boy—looked more with-it than you do at this moment. Now, sit down, pile high your plate, for you are still a growing boy, and let us begin our magnificent banquet.”

It was always something to watch the fat man eat a meal. Every slice of pizza, every forkful of roasted vegetables, every hunk of garlic bread, spoonful of pudding, and delicate triangle of baklava was scrutinized with the intensity of a jeweler examining a fine and rare stone. Sometimes the fat man would even pause after his assessments to say something like, “The crunch of pizza crust sounds like the crackle of distant lightning in the middle of a summer’s night, when you were still young enough to dream that Martian spaceships were hiding up there,” or “There’s nothing, nothing , I say, like the smell of steam from a hunk of warm, fresh-baked bread when you first tear it in half; it’s the gentle comfort of picturing Grandma in the kitchen baking through the night because you’re visiting and she has no one to bake for since Grandpa passed away,” or “The sensation when you first take a cold drink is like feeling this glorious bird made of ice spreading its wings in your chest, giving you the power of flight with every chill so you can soar up above and leave all the cruelty of man,” and “It should be a sin for a person to gobble down a truly excellent cheeseburger; it doesn’t matter if you’re eating at a restaurant or backyard cookout, somebody bygod took the time to cook it with their own hands, and their labors should be appreciated, even if they never know how much you admire their skill with a grill and spatula.”

Читать дальше

![Lord Weller - Ритера или опасная любовь [СИ]](/books/421202/lord-weller-ritera-ili-opasnaya-lyubov-si-thumb.webp)